With a devoted customer base and ever-increasing adherents, the idea of sustainable design and manufacturing is promising. However, it almost immediately falls prey to a fundamental flaw: a supply of materials. As sustainable as a design may be, it has to be realized with existing materials – materials that, all too often, are composed of irresponsibly-sourced forest products, petroleum-based compounds, and other unsustainable supply chains.

Even when when sustainable materials are available, as in the case of certified woods or post-consumer papers, they tend to carry a higher price tag for their sustainability credentials. As a result, designers and builders can be reluctant to work with them.

One of the most confounding things about the sustainable materials dilemma is that there is no lack of raw materials. Every year, millions of tons of wood, paper, and other cellulose-based materials are recycled – and millions more burned, placed in landfills, or otherwise disposed of. If manufacturers could find a way to cheaply collect and reuse all that raw material, one of the major hurdles to low-cost sustainable manufacturing would be cleared.

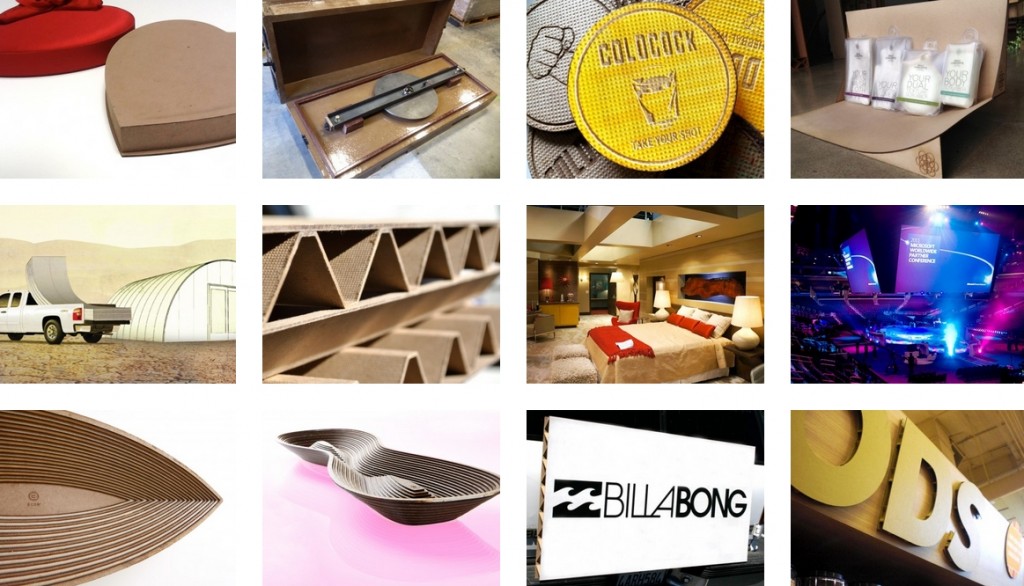

One product that may help clear that hurdle is Ecor, a material produced by San Diego-based Noble Environmental Technologies (Net). Made from waste cellulose, Ecor panels are dense slabs reminiscent of cardboard or fiberboard. They can be made in a variety of sizes or densities, which can then be folded, cut and glued into an array of shapes. This flexibility makes it useful for hundreds of applications, from making furniture to building construction, binding books to making signs. Because it is composed of cellulose, Ecor can be completely recycled, or completely constructed from recycled materials.

But Net CEO, Robert Noble, is looking far beyond a cardboard replacement. His company has worked with the military, as well as private manufacturing companies, to develop versions of Ecor that replace everything from plywood to honeycomb aluminum. And, while the company is close-lipped about its potential partnerships, it isn’t hard to see how Ikea, Home Depot, and other furniture and home-repair retailers would be interested in cheap, sustainable boards.

The key word is cheap. For now, Ecor’s biggest problem is the same one facing any other sustainable material: price. The company is in what Noble calls “lab-scale,” production, a level that he says is very expensive. “Currently, our cost ranges from – per square foot,” he says.

To lower costs, NET is investing in large-scale production. Early this year, its first factory, which is located in Serbia, will scale up to 24-hour production, a level at which prices will drop sharply.

“Our production costs will come down below 15 cents, if not below 10 cents per square foot,” Noble claims, noting that, at that level, Ecor will be competitive with plywood. The company’s next move will be to open a facility in the United States, possibly followed by one in western Europe.

Net tends to wax romantic about Ecor’s potential; on its website, the company sells several Ecor consumer products, including ornaments, pop-out animals and strangely topographic bowls, all of which clearly owe their origins to the two-dimensional Ecor material. Noble notes, however, that Ecor can also be used to produce three-dimensional products. The company has already patented several forms, and plans to roll them out in coming years.

Zeoform’s future

For all its flexibility, Ecor isn’t likely to give plastic a run for its money, at least not in its present form. However, at least one other cellulose-based material seems poised to step into the gap. Zeoform, an Australian company, has a cellulose-based material that, it claims, can be produced in a variety of densities, from a cork-like product to a denser one that resembles bakelite. Furthermore, Zeoform material can be easily cast, a factor that could make it attractive to artisans and small-scale manufacturers.

In 2006, as part of its product testing and promotion, Zeoform has enlisted the help of Wilma van Boxtel, a Perth-based artist who used the material to make pad-like stools, which she calls “poofs”. “It was interesting to work with,” she said. “It’s like plastic. I could do the same things as with wood. But it was more flexible: with wood, you can only have planks, but I was able to do more organic forms.”

Unfortunately, after her test production, van Boxtel was unable to get hold of more Zeoform. “I’m still waiting until the material is available for large-scale production,” she says.

But, as with Ecor, price – and access – are serious considerations when it comes to Zeoform. While the company has proved what CEO Alf Wheeler calls a “proof of concept” scale, it is not anywhere near a marketable level.

Ultimately, he predicts, that it will be as low as “ten dollars per kilo”, a price that, he says, will make it competitive with “hardwoods, wood composites, ceramics, and high end resins”. For Zeoform, the future may well be filling the space currently occupied by plastics.

But, unlike plastics, the raw materials for zeoform – water and cellulose – are widely available at low cost. Wheeler notes that “our material is processed down to the microfiber level,” a factor that enables the company to use a wide variety of industrial, agricultural, and post-consumer waste. “It’s an important part of our business model that we never, ever take away food to make materials,” Wheeler explains.

Right now, the company is using microfiber waste from textile manufacturers. These short fibers, which are useless for cloth, are perfect for Zeoforms. However, Wheeler notes, the company’s flexibility could potentially make it possible for the company to play suppliers against each other. “If the cotton grower gets a little greedy and overprices his cotton waste, it will cease to be a viable feedstock for us,” he explains. “Luckily, there are millions of other sources for cellulose waste for us.”

As anybody who is familiar with ethanol will note, the law of unintended consequences is always in effect when one works with agricultural materials. However, Net and Zeoform have worked raw material flexibility into their business models, which may help ameliorate the sorts of stresses that ethanol production has placed on the food system. Both Noble and Wheeler note that their cellulose products can be manufactured from a variety of materials, from recycled cardboard to textile waste to agricultural waste to what Noble calls “bovine processed fiber” – and the rest of the world calls “manure”.

As for Wheeler, he admits that landfill material may not be suitable for making Zeoform; for that reason, his company is focused on diverting waste from landfills. Even so, both Zeoform and Ecor hint at an especially attractive future: one in which companies are able to profitably sell, and consumers are able to profitably use waste materials that they once buried in the earth.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.