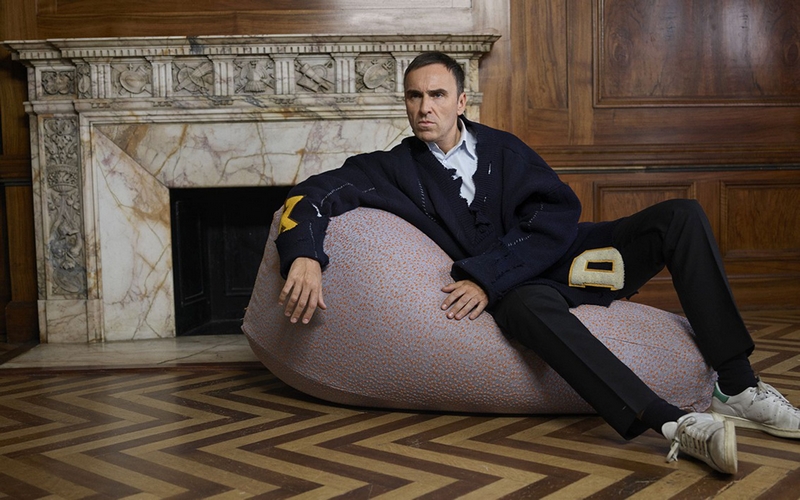

Raf Simons x Kvadrat 2019; photo: kvadrat.dk/designers/raf–simons

Fashion’s loss is a win for textiles as the designer’s ongoing collaboration with the Danish firm is producing some of his best work yet

I was half expecting to find Raf Simons in an introspective frame of mind in the early months of 2019. The previous year had not ended well for the Belgian fashion designer, who had been lured to New York in 2016 to revive the famous but financially flatlining house of Calvin Klein. Put in creative charge of everything from jeans and knickers to bespoke ballgowns and branding, Simons had been briskly dismissed less than a week before Christmas. The company has now shut its luxury collections business to focus on denim and underwear.

In late February, Simons could hardly be more upbeat, and that’s after six days in bed laid low by a serious bout of flu. “Just a few days out of the studio and it’s almost impossible to catch up,” he says, his phone flashing and burping with a deluge of calls and texts. “All these people trying to get hold of me.”

Though Simons might no longer have a place at Calvin Klein, there is plenty to keep him busy. His own menswear line – a niche but influential success since its launch in 1995, with its intermingling of street style and tailoring – is delivered from his Antwerp studio by a staff of just eight. “So I’m never without a job,” he laughs. And then there is his ongoing collaboration with Kvadrat, the Danish textile company, that has allowed Simons to do some of his most innovative work, the latest of which will go on show in Milan during the Salone in a sprawling show space that was once a mechanic’s workshop and is now called Garage 21.

The Milan presentation will centre on three demountable houses by architect Jean Prouvé – La Maison Tropicale flatpack designs developed by the Frenchman in the early 40s to eleviate housing crises both at home and in the French colonies. Simons plans to install them in a garden full of flowers created by the Belgian florist Mark Colle, and turn their interiors into both domestic spaces and atelier-type workshops, to tell the stories of the three new fabrics he has created. “And we’ll have a cafe, and a space for social interaction. It’s not a showroom, it’s an environment, a place of inspiration,” he continues, before stopping himself abruptly. “I hope it’s as good as it sounds. It’s so much more massive than anything we’ve done before.”

This, of course, is slightly false modesty: Simons the fashion designer is no stranger to the big production. His latest runway show for his own Raf Simons line took place in January in the ballroom of Paris’s drippingly deluxe Shangri-La hotel, “though we lit it quite trashy, and had a live Belgian band that started playing halfway through,” Simons says. At Jil Sander, where he was creative director from 2005-2012, he sent flashes of dazzling colour through collections that had traditionally been navy and beige, and commissioned a series of groundbreaking store designs. In New York, the ground floor contained no clothes at all, just a sculptural series of continually rotating marble louvres.

Arriving at Dior in late 2012, he broached couture for the first time by showing it in a venue where the walls were turned into colourfields of blue, white and yellow, thanks to a million flowers. “That was Mark Colle’s work,” he says. (Nothing to be worried about for Milan, then.)

Photograph: Willy Vanderperre

Some of Simons’ designs for Dior – a stunning red coat with a gold belt; a baby-pink mini tulle ballgown – are currently on show in London, at the V&A’s exhibition dedicated to the design house. “He interpreted the codes of Dior – the waisted shape – very well and made people want to wear it again,” says Oriole Cullen, the curator in charge of the show, where Simons’ looks hold their own against previous incumbent John Galliano’s mad historical fantasies and successor Maria Grazia Chiuri’s girlish interpretation. “But it was his eye for colour that really came to the fore.”*** SSimons left Dior after three years, perhaps in the knowledge that he wasn’t quite the right fit to keep the label’s ladylike DNA in continual evolution. His own line has made him an inadvertent hero among the hip-hop fraternity – A$AP Rocky is a super fan – which gives some idea of his more natural inclinations. By 2016, he was at Calvin Klein, wowing fashionistas – if not the cash tills – with Road Runner sweaters and marching band pants. The signatory of a serious NDA, he’s not at liberty to discuss what went on in New York. “But what you read and what actually happened are not always the same thing,” he says discreetly. And anyway, he’s happy to be home: “I love the smallness of Antwerp.” An ardent art collector, he is starting to look locally for a space he might eventually turn into a museum. “I want to make things public. I’m not interested in setting up a really private private foundation,” he says. “Rather something with education and collaboration built into it.”

But also, as his collecting becomes more ambitious – a recent acquisition includes an enormous aquarium work by the French artist Pierre Huyghe – he needs to think about what to do with the work. “It’s quite a responsibility. I’m not exactly buying things you can ship back home in a crate and hang on the wall.”

Kvadrat’s CEO Anders Byriel is as passionate about contemporary art as Simons. “That and the fact that we’re the same post-punk generation,” Byriel says. “We’d liked the same clubs, the same music.” Simons had discovered the textile producer when, while working at Jil Sander, he was looking for fabrics so stiff, the clothes would stand up on their own. He became increasingly interested in the brand.

Photograph: D/©Anne Collier

Byriel is the son of co-founder Poul Byriel, who set up the company in 1968 with Erling Rasmussen. The headquarters are still in Ebeltoft, a tiny old port on Denmark’s east coast, with one spartan hotel and a pretty good glass museum. The fabrics it produces, developed primarily for upholstery, are steeped in innovation and quality. You’ll have encountered them in theatres, museums, banks and hospitals all over the world, lusciously hued and densely woven for maximum longevity. Byriel has always chosen his creative collaborators carefully, asking architect David Adjaye to design the Kvadrat London showroom in 2009, and bringing the maverick graphics star Peter Saville on board as a sort of brand seer.

In 2011, Fanny Aronsen – Kvadrat’s senior designer and an exceptional combination of academic and designer – died; she was in her early 50s. “We were a bit paralysed by her passing,” Byriel says. “It took us a couple of years to recover. Then we realised that Raf was already working with us, in a way, and we thought this was a chance to make the fashion connection.” Simons was given nearly two years to develop his first fabrics for the company, examining the colourways and weaving processes of fashion fabrics, and adapting upholstery yarns to create similar effects. Outcomes included Argo, a long-fibred mohair that feels like sheepskin, and Noise, where the uneven nobbles of bouclé were reinterpreted through mad dashes of contrasting colours. “He’s brought in an entirely new audience, particularly in the interiors market. I don’t think I’ve been to an art collector’s home recently and not seen a Raf Simons fabric somewhere,” Byriel says.

a Tecta D51 chair by Walter Gropius

For Simons, his collaboration with Kvadrat is another notch in a career that has been punctuated by ancillary projects – from curating art shows to making photographic books and teaching for several years at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. “It frees you up if you go and do something different,” he says. “But also, I’ve never officially defined myself as a fashion designer, maybe because I didn’t study it.”

Instead, he studied industrial design at the School of Arts in the small Belgian city of Genk in the mid-80s, obsessing over mid-20th century designers such as Franco Albini, Le Corbusier and interior designer Jean Royère, while his peers were more excited by the contemporary work of Philippe Starck and the lingering power of the brightly coloured Memphis Group. “I was more into people who had a strong relationship with social responsibility, like Jean Prouvé and Charlotte Perriand,” Simons says.

But working with Kvadrat also offers an important antidote to a fashion industry that has become increasingly fast and furious, particularly in the last decade. Simons describes the collaboration as “calming”. Fashion, not so much. “It’s been changing since the 90s,” says Simons, who’s 51 and has been in the business for 23 years. “In the past, a designer made a collection and presented it to a small audience of professionals, then one picture appeared in a magazine, and months later the clothes came to the shops. Oh my God, the desire that created! Now everyone sees the runway show right away, and by the time the clothes are available, people have moved on to something else. This fast communication, it’s exciting but it can be dangerous, too. Damaging.”

Photograph: ©Anne Collier

At Kvadrat, Simons is able to take as long as he wants, making endless prototypes in order to create new products, while Byriel has decided not to look at the budget but rather at the end result. “Raf is more expressive and emotional and edgy than a classically trained textile designer, and we want to make the most of that,” he says. Kvadrat, which has trebled its business in the last eight years by expanding into the US, China and Japan, can presumably afford to take this risk.

In Milan, the latest results will appear in the form of three very different fabrics, including a new corduroy called Phlox whose ribbing is, according to Simons, as thick as a finger. “It’s a reference to the 70s, but a completely blown-up version,” he enthuses. “And it won’t be in brown or beige.” The chunky, short-piled textile will be in Simons’ go-to colours – cobalt blue, bright pink and sunshine yellow. Novus is a further development of an existing faded grid design which goes back to Simons’ love of Jean Royère and his Eiffel Tower collection. While for the last, Atom, he has achieved the near impossible feat of making a textile with no discernible repeat: “Like a flower field,” he says, “where the points of colour go randomly on.”

This he will show not in lengths or as upholstery, but reduced to a kind of dust, which certainly suits the slightly dystopian title of the show, which is No Man’s Land. I suspect, though, it is more the wonderful world of Raf – one where music and fashion and flowers and architecture and dazzling colour all come together – that awaits us in Milan.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.