The decade has not been kind to Manteigas. Nestled in the mountains in the Portuguese interior, this pretty town has suffered a familiar kind of slow-motion decline.

“Once the factories started closing, then the schools closed, the shops closed, even the chapel closed,” says Maria José Santos Salvado, a wizard with needle and thread who was laid off as a textile patcher when her factory shut in 2011. “All the young people left. Manteigas became a town of old people.”

It’s a common enough story in southern Europe, where rural decline is a long-term tendency that has accelerated since the financial crisis.

But are fortunes about to reverse for people like Salvado? After the surprise intervention of a husband-and-wife team from Lisbon, the looms of her old factory are chugging noisily once again. With orders streaming in from as far afield as Japan, her deft skills are in higher demand than ever.

Isabel Costa, formerly a high-flyer in Portugal’s corporate retail sector, and her lawyer husband, João, are among a small but growing number of investors turning their eye to Portugal’s rural interior.

It is no easy task. Years of economic decline following the 2008 banking crisis, coupled with harsh government austerity measures, have hit the country’s rural regions especially hard. Between 2014 and 2017, the population of Portugal’s interior declined by 5.6% as birth rates stalled and young people left. Business activity (or lack of it) has followed suit.

Although Portugal’s economy is now finally getting back on its feet again (GDP grew by 2.8% in 2018), the vast bulk of this growth is concentrated in Lisbon and a handful of other (mostly coastal) cities.

In many parts of Europe, the issue of depopulation of the countryside, regions, or in some cases whole countries, weighs on the minds of politicians and the public, as an era of freedom of movement means more people are able to migrate to find better opportunities.

A recent study by the European Council on Foreign Relations showed that in Spain, Italy, Greece, Poland, Hungary and Romania, countries where the population has either declined sharply or is flatlining, more people are worried about emigration than they are about immigration.

The problem is felt acutely in central and eastern Europe, where populations have shrunk dramatically in the decades since the fall of communism, due in part to the traumatic effects of the transition, with high mortality rates, low birth rates, and millions of people travelling to western Europe to seek higher salaries, especially in the years after EU accession. In Bulgaria, for example, the population has shrunk from 9 million to 7 million since 1989.

“More and more people are investing in the interior of Portugal … but they need to look at these projects almost as a kind of mission, not as a way of getting rich,” advises Costa.

This is true of her own venture, which, despite growing year-on-year, was never designed to be a major money-spinner. Indeed, its origins were more coincidental than commercial. Costa had placed an order with a local manufacturer for burel wool – a historical speciality of Portugal’s mountainous Serra da Estrela region.

She quickly discovered that the manufacturer was in a “bad situation” and agreed to buy its working looms and its back catalogue of patterns. She rented a disused factory space owned by the local council, re-hired 15 of the firm’s employees, and restarted operations.

With some luck (Microsoft hired her to refit its Lisbon headquarters) and plenty of hard work (she spends half the year travelling to trade shows), Costa’s Burel Mountain Originals brand now employs more than 60 people and supplies two high-end stores in Lisbon and Porto.

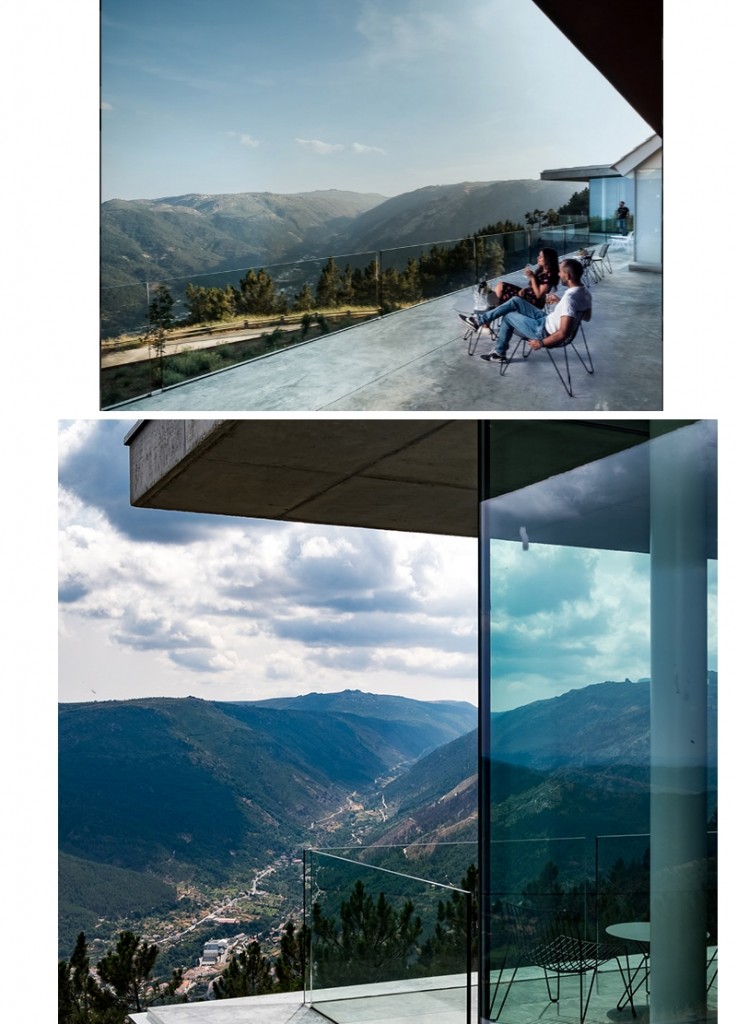

“We couldn’t just sit back and see this incredible heritage destroyed. I couldn’t sleep knowing about this problem and doing nothing to retain the area’s industrial history and to teach the next generation,” says Costa, who also owns two boutique mountain hotels close to Manteigas.

Catarina Vieira is of a similar mind. A former finance manager from the coastal city of Aveiro, she owns a modest six-chalet quinta, or estate, near the town of Seia and is a vocal proponent of Portugal’s nascent eco-tourism market.

Photograph: Rupert Eden/Burel PR Handout

Chao do Rio is the polar opposite of the vast, package-holiday complexes that now litter the Algarve. The food she serves is all locally sourced, the swimming pool is “biological” (read: unchlorinated and teeming with frogs), and the only loud music you will hear is the sound of birdsong.

“The whole idea behind projects like ours is that they are on a small scale and they show concern for the environment and social awareness,” says Vieira.

Her vision of a small-scale, culturally-sensitive mode of development is shared by many of those investing in Portugal’s interior. Like Bruno Vargas. A 41-year-old former marketeer, he jacked in his city job five years ago to run a four-hectare farm in Rio Maior, a village located in the Centro region.

His venture, Herbas Organic Herbs, specialises in hand-crafted aromatic tea infusions. Business is good. He exports to various European countries and employs seasonal labour from the local area. By his own admission, however, the venture grew out of the “romantic idea” of a more balanced lifestyle as much as turning a profit.

Ever wondered why you feel so gloomy about the world – even at a time when humanity has never been this healthy and prosperous? Could it be because news is almost always grim, focusing on confrontation, disaster, antagonism and blame?

This series is an antidote, an attempt to show that there is plenty of hope, as our journalists scour the planet looking for pioneers, trailblazers, best practice, unsung heroes, ideas that work, ideas that might and innovations whose time might have come.

Readers can recommend other projects, people and progress that we should report on by contacting us at theupside@theguardian.com

“I had the idea that it would be a different kind of life, with more time for my family and less pressures. That’s not turned out to be true, of course. If you have a business, you have pressures, but at least my mind is clearer about why I’m doing this,” he says.

Not all embrace this pared-down model of rural development. The Portuguese government provides warm words, for instance, but little in the shape of financial support. Such public investment as exists for rural enterprise development tends to come from the European Union.

To get started, for example, Vargas received €40,000 (£37,000) in seed-funding from ProDer – a nationally-managed fund for rural development primarily financed by the EU. Costa and Vieira also received help from the same fund.

Even less sympathetic are large-scale investors, for whom big is – as ever – beautiful. Despite being located in an officially designated natural park, for instance, Manteigas is soon to have a huge, luxury hotel constructed in the wooded glacial valley overlooking the town.

In a similar vein, international mining firms are now sniffing around. It transpires that Portugal’s central belt is especially “blessed” with reserves of lithium, the alkali metal used in batteries for smartphones and electric cars.

“If mega-mining comes to the centre of Portugal, it will spoil everything. We really need to cherish these small projects and put away these crazy dreams of Portugal as the future Arabia,” says Vieira.

Photograph: PR HANDOUT

The economists would disagree, arguing that mega-mining and commercial tourism promise far higher levels of capital investment and job creation. The central government, which campaigners fear is poised to greenlight a lithium mine on the edge of Serra da Estrela, appears to agree.

From his holistic yoga retreat near Tábua, in the district of Coimbra, Tony Speirs is watching with anxiety. Originally from north Wales, he set up shop in central Portugal a decade ago. Over that time, he has seen large-scale commercial investment completely alter the once sleepy coastline of the Algarve. He hopes his neighbours will take note and opt for a different route.

As he himself readily admits, micro-enterprises like his will not transform Portugal’s rustic interior into dynamos of economic development. But they are helping spark into life pockets of entrepreneurial vitality. For Speirs, that’s enough. His neighbours, he says, are of like mind: “Here, people think once your business is working, why grow it?” Why, indeed?

This article is part of a series on possible solutions to some of the world’s most stubborn problems. What else should we cover? Email us at theupside@theguardian.com

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.