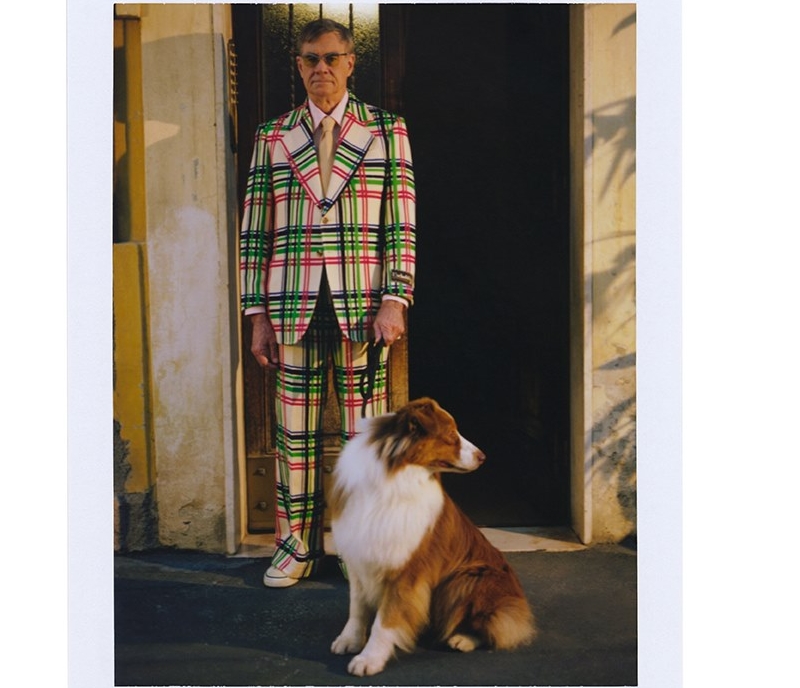

For his cameo appearance in Episode 7 walking a dog out of the building Silvia is standing in front of, director Gus Van Sant is dressed in a Gucci windowpane suit with a silk shirt and tie. @Photography by Gus Van Sant. Watch all episodes from the 7-Part series on.gucci.com/GucciFest_.

At home in California over lockdown Gus Van Sant, king of the Hollywood underground, was, like the rest of us, binge-watching Netflix. “Ozark, that was good,” he says of the drama about the wholesome, apple-pie Byrdes, whose family business in a sleepy lakeside town happens to be money-laundering for a ruthless Mexican cartel. “Although, you know, kind of grisly.”

Van Sant’s latest project, by contrast, is all glamour. He has shot a seven-episode miniseries for Gucci in collaboration with the brand’s creative director, Alessandro Michele. Ouverture of Something That Never Ended takes an esoteric day-in-the-life format, following Silvia, played by Silvia Calderoni, from the moment she wakes up and steps into her high-heeled gold house slippers. She has a pee in black lace knickerbockers and queues at the post office alongside a woman in a kaftan with a basketball under one arm, and a man in a football shirt carrying a canary in a cage. She goes to a cafe, a dance rehearsal, and walks the streets of Rome – with a new outfit for each activity. The film doubles as a streamed catwalk show for Gucci’s new collection, with 10 new-season looks making up the wardrobe for each episode. There is even a cameo by Harry Styles.

After a 20-day shoot in Italy, Van Sant has just arrived back at his home in Los Angeles’ Los Feliz hills, overlooking the Hollywood sign and the Griffith Observatory. We had been scheduled to meet over Zoom from Rome, but our interview got pushed back, and we’re talking over the phone instead – understandable, since it is 7am in LA, which is no hour to Zoom. “I’m still on Italian time, so it’s fine,” he insists politely. But he sounds a little bleary, clearing his throat in a way that suggests answering my call is the first time he has spoken since last night.

A film underwritten by a luxury fashion house and dotted with thousand-pound handbags isn’t where you might expect to find the seminal arthouse auteur whose most recent work, Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot was a comedy based on the memoir of quadriplegic cartoonist John Callahan. But Van Sant’s career has been a series of plot twists. After the indie poetry of Drugstore Cowboy and My Own Private Idaho, he made a handbrake turn into brittle, brilliant satire with To Die For and slam-dunked a major hit with Good Will Hunting before reappearing with the minimalist oddball comedy of Gerry and the discordant, Columbine-adjacent Elephant. And in this resistance to categorisation, Van Sant has something of a kindred spirit in Michele, a rock-star fashion designer who dresses like a left-bank intellectual sketched by Karl Lagerfeld, and who cited his inspiration for a recent Gucci show as the stage wear of Elton John and the writings of Martin Heidegger.

For all the Gucci logos – and there are many – the most white-hot fashionable thing about Ouverture isn’t the haute-lockdown tracksuits in ruby satin or even the gender-blurred styling (one elegant young man rides a bike in shorts, sport socks and a petite cross-body white handbag) but the episodic structure. Like films, catwalk shows are traditionally standalone events. But with the rise of the box set and of award-wining multi-season drama, being sliced into chapters no longer relegates culture to soap opera status. In 2020, box set is the new black.

Van Sant has little time for Hollywood hand-wringing about the demise of cinema culture. “That structure has always been there, if you look for it. The idea of the next instalment of the story has been around since Oliver Twist was serialised in newspapers. James Bond was episodic. Star Wars was episodic. It was just that you saw them a year or two years apart. So I’m not saddened by that.”

Of all the Hollywood legends Van Sant has worked with, none was a bigger deal than directing Sean Connery, as he did in 2000’s Finding Forrester. Van Sant was 10 years old when Connery made his first Bond film: “For a person my age, Sean Connery is James Bond. And of course I grew up watching those films.” Connery, playing a reclusive genius author, was “just a great person”, says Van Sant. “He was a legend by then, and a committed actor, and knew all the tricks in the book.”

The ritual of cinemagoing is semi-sacred in Hollywood lore, but Van Sant is not particularly wedded to a tradition currently on pause in favour of home entertainment. “The big screen, and people going to the cinema – it became a romantic notion, but it didn’t start like that.” If the technology had existed to make miniature “nickelodeon machines” for watching movies, the whole history of cinema would be different, he says. “Big screens were a corporate necessity. They were a distribution model designed to show a film to the most viewers. And now there’s a new way, because we each have a device that we hold in our hand and watch a movie on – it’s called a phone.” But still, there is something new and strange in the way that cinema has been “sucked into the computer screen” along with the rest of our lives in 2020. “It’s kind of a strange thing, to be watching cinema on the same computer screen where you buy your groceries,” he chuckles.

Ouverture is a commercial project with an arthouse vibe. The lyrical palette of pistachio and fuchsia has Michele’s handwriting, but the way ideas and moods ebb and flow below the surface without necessarily being spoken out loud is pure Van Sant. Gerry and Elephant were made without conventional screenplays, with only “paragraphs or sentences that indicated what was supposed to be happening”; in the first episode of this miniseries, there is no dialogue except that of punk trans philosopher Paul B Preciado speaking about gender and identity on a TV show.

If that sounds unusual territory for a brand whose classic loafers and timeless handbags are the genteel uniform of the business-class lounge, note that with Michele at the helm, Gucci has taken a distinctively progressive stance on gender and identity. Menswear and womenswear have been merged on the catwalk since 2017. The mood music of Michele’s Gucci chimes with Van Sant, who is so disarmingly comfortable with ambiguity that he often answers my questions by both agreeing and demurring at the same time.

“When Alessandro told me his ideas for this project, I thought, yeah, I know this territory pretty well,” says Van Sant. Relationships and characters from outside the canon of heterosexual romance have centred in his lens for decades. It was 15 years after writing the screenplay for My Own Private Idaho when, by persuading River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves to take the lead roles, he finally secured financing for a story about homosexuality, unrequited love and marginalisation that had been considered too risky by the Hollywood establishment. To Van Sant, Gucci giving the starring role in Ouverture to Silvia Calderoni, whose gender fluidity has been likened by the New York Times to quicksilver, reflects “the growth of acceptance of difference, on the planet. As opposed to relegating the identities of certain people”.

For a progressive film-maker living in America, the direction of cultural travel in recent years has not been straightforward. Arriving as the drama of the Trump years was reaching its climax, the pandemic “was almost like the strange sauce on top of everything else”, says Van Sant. A film based on a Michael Chabon essay about visiting Paris fashion week, which the director had spent 18 months adapting into a screenplay, had been slated to begin shooting in April. “But I live by myself, so being quarantined was very similar to how I live anyway,” says Van Sant. “In terms of work, it was pretty much business as usual.”

In the meantime, he painted a lot. A fine arts student before he switched to film-making as a major, Van Sant has had painting as a sideline since the 70s – the painting on the wall in Robin Williams’s office in Good Will Hunting is one of his – and he had his first solo art show in New York last year.

He also worked on some screenplays, including a series about a gay president, although it was, he says, a difficult time to make stuff up about a president, because “it felt overshadowed by the real presidency, which was so extreme that it put the imagination of writers to shame. We were living through a wilder story than any we could imagine.” In the past couple of months, he says, he mainly tuned into the same story everyone else did. “Mostly, you know, I watched CNN.”

• Ouverture of Something That Never Ended can be seen at guccifest.com.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.