Go East is a curious exhibition. The name suggests a grand and sweeping overview of the art of an entire region of the world and it’s certainly that. But it’s also a curious venture because of the way the show is curated, staged and promoted. Split into two parts, the bulk is at the Art Gallery of NSW, while the other part – consisting of a single giant artwork – is in Paddington at the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF).

Before we discuss the art, some background. The South African-born Shermans are a key power couple in the Australian art world. Brian is a self-made multimillionaire whose passion for art, animal welfare and philanthropy is probably only equalled by that of his wife, the indefatigable Dr Gene, who ran the Sherman Gallery, one of Australia’s leading contemporary galleries for 21 years until 2008 when it morphed into the foundation.

The foundation is dedicated to exhibiting work from Australian and Asia-Pacific region artists and so, beyond the exhibitions it has staged, the Shermans have also bought a considerable amount of art from this very loosely defined area, predominantly by contemporary Chinese artists, but also by a selection from Japan, Tibet, India, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines, as well as some artists now resident or born in Australia, the UK and elsewhere.

That exhibitions based on private collections tend to be more illustrative of the taste of the collectors than evidence of a coherent curatorial survey is just one of the problematic aspects of Go East. The rather expansive definition of what constitutes Asia – and the nature of the collection itself – waylays any claim for the show to be more than an admittedly fascinating peek into the Shermans’ horde. How this show came into being is explained by a quote from artist Ai Weiwei on the art gallery’s web site: “Everything is art. Everything is political.”

With 30 individual works spread through the foyer and upstairs space at the Art Gallery of NSW, the immediate standouts are the eye-catching installation of Lin Tianmiao’s Badges (2009) and Jitish Kallat’s Public Notice 2 (2007). Both works are about language: Tianmiao’s giant circular embroidery frames spell out words in Chinese and Pinyin (Chinese words written with Latin letters).

Kallat’s long installation wall work features the text of a speech given by Gandhi in 1930, as he walked 390km to the coast to make salt from sea water in defiance of the British government’s salt tax. Gandhi’s words are rendered in resin and made to look like bones, placed on shelves against a bright yellow wall.

Both Kallat’s and Tianmiao’s work mix the decorative with meaning to mixed results. While both have a visual impact, the treatment of the text is either ambiguous, as in Tianmiao’s work, or overdone, as in Kallat’s.

The rather serene ambiguity of Ai Weiwei’s works is a pleasurable contrast. Overcoat (2009) is a mounted and boxed military winter coat of the type the artist gave away to the poor, his name subtly embroidered on the inside. The wall text informs us that the artist liked the fact the recipients of his charity were unaware they were wearing a work of art and wouldn’t care if they did know. The large wooden box of paper and the mounted and framed calligraphy of his 2015 work, An Archive, has both presence and blankness – unless you read Chinese the content of the work eludes you but, like the winter coat, it exists as both an object and idea.

Shigeyuki Kihara, an artist of Samoan and Japanese heritage, is represented in the collection by a series of photographs in which she performs the cliches of western art in a series of poses that recall exotica of the 19th and 20th century while also undermining expectations of gender and family roles and femininity.

The intentional confusion of sign and meaning in Kihara’s work is a link between many of the works in the exhibition, but where in western contemporary art the “truth” of the work is much more apparent to the western viewer – and usually effaced by irony – the work in Go East relies on an understanding of very specific cultural contexts. Kihara’s art is accessible in a way that many others here are not.

Yang Fudong’s 2004 work Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest Part 4 (Still) is decidedly ambiguous even when you learn that it is a still from a movie.

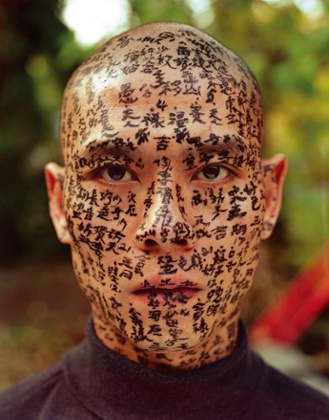

Zhang Huan’s Family Tree (2000), a series of nine images of the artist’s face progressively overpainted with Chinese text until it is black, feels significant without a real sense of why.

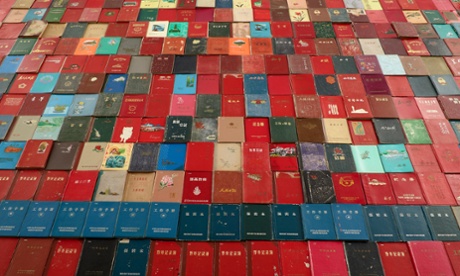

Over in Paddington, Yang Zhichao’s Chinese Bible (2009) is a massive performance installation work of 3,000 personal diaries bought by the artist from a market, each used by an unknown person some time between 1949 and 1999, accompanied by a video on the wall of the artist cleaning each diary cover by hand. Looking into various diaries, you find within a variety of uses – a personal journal, a sketchbook of images, a schoolbook, a doctor’s notebook and so on – with iPads providing translations of small sections of the texts. The work charts the impact of decades of tumultuous post-war Chinese history as seen by the people who lived it. Yet that experience remains at a distance, too, formally impressive but emotionally ambiguous. In the face of all this, what are we meant to feel?

- Go East: the Gene and Brian Sherman Contemporary Asian Collection is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and SCAF until 26 July

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.