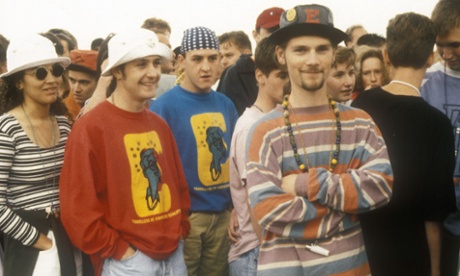

Early on in the new series of This is England, we see Lol working as a school dinner lady and dealing with her old friend Gadget, who has arrived to cadge a free lunch. He is dressed in a bucket hat and an oversized hoodie in colours so bright you want to turn down the contrast on your screen. You immediately know that we’re in 1990, the era of “Madchester” T-shirts, bowl cuts and centre partings, and ridiculously flared Joe Bloggs jeans.

Decades rarely behave as we’d want them to, of course, falling neatly into 10-year segments to facilitate retrospectives. If we want to trace the roots of Gadget’s getup, we have to go back to the summer of 1988, when the acid house explosion turned the clubworld day-glo. Fuelled by a potent mix of house music, MDMA and a restless feeling that something needed to change, the scene swept across the clubs of London and Manchester like a tsunami, clearing out everything that had come before it. Almost overnight, the old club uniform of Levi’s 501s, Dr Martens, crisp white shirts and even sharper flat-top haircuts was replaced by clothes that were bright, baggy and easy to dance in, and hair that hadn’t seen a barber for quite some time.

By 1989, with outraged tabloid stories acting as the best publicity any promoter could wish for, the scene had spread across the UK. Clubbers were converging on illegal raves in fields and aircraft hangars around the M25 in numbers that left the police helpless, and all the tribes of 80s youth culture were briefly united – one nation under a groove. With crowds of more than 25,000 gathered at some of the bigger raves that summer, there was room for anyone who could afford the price of a ticket, and the old divides between black and white, gay and straight, indie and dance, north and south, and even rival football teams were forgotten. Margaret Thatcher had declared there was “no such thing as society”, but for a brief, heady time it felt as if we had forged a hedonistic new society of our own.

It’s easy to forget now how grim things were back then. Eastern Europe was rising up, the Berlin wall had fallen and Nelson Mandela finally walked out of prison in South Africa, but the winds of change had blown out into a gentle breeze by the time they reached the UK. Thatcher was finally deposed as PM after the poll tax riots, only to be replaced by John Major doling out more of the same austerity and blame. The popular image of him was from the satirical TV show Spitting Image, which portrayed him as totally grey. It felt like no coincidence that youth culture had meanwhile burst into defiant, glorious technicolour.

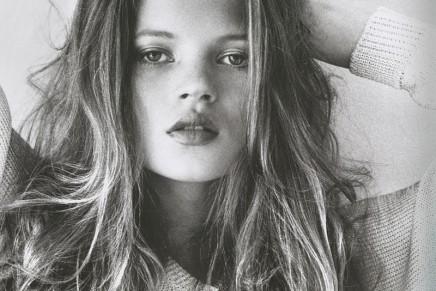

At the time I was editor of the Face magazine, and in May 1990, we did a fashion story inspired by the upcoming World Cup in Italy, photographed by Mark Lebon. For the cover, we featured a new, young model from Croydon, dressed in an Italia 90 scarf and clutching a football. Three months later, we featured her again, this time wearing a feathered headdress and a goofy smile, photographed by Corinne Day in an issue celebrating the Stone Roses’ huge gig on Spike Island and the wave of new bands coming up in their wake. That cover has since come to symbolise the new mood. The model, of course, was Kate Moss.

“I used to just wait and study her, to try and get it as documentary as possible,” Day told me years later. “I wanted to get her character and her personality and her presence in the pictures. Because fashion really wasn’t about that in the 80s – it was the photographer directing the model. I really wanted to reverse that and make it about the model, to really get her character. And I think that’s how Kate got noticed.”

Day was one of a new generation coming up through the Face and i-D magazines, including photographers such as David Sims and Juergen Teller, and stylists such as Melanie Ward. “Because we were all new, it was hard for us to get designer clothes [to photograph], so we’d go to markets and we’d make up fashion that we liked,” said Day. “We made this kind of grungy style, and [made] second-hand clothes really fashionable. And it was great, because people didn’t have much money anyway.”

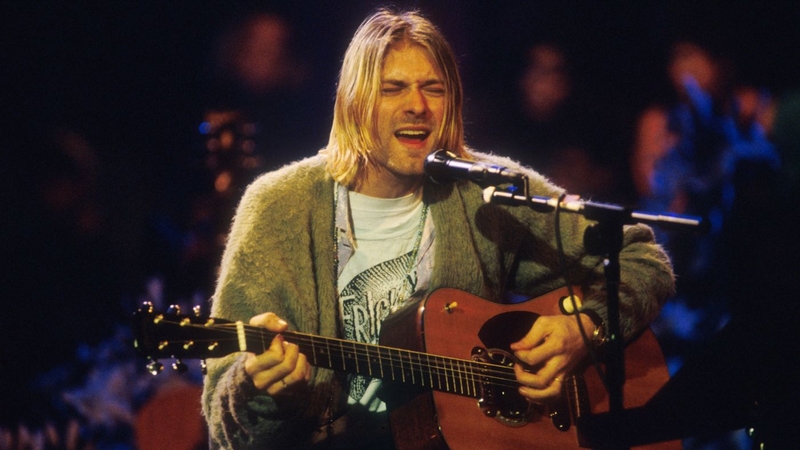

It took US youth culture a little longer to scream its defiance, but it came in spectacular style towards the end of 1991 with the cathartic fury of Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit. Generation X had found its voice in Kurt Cobain and the Seattle grunge scene, and their brand of thrift-store chic quickly became the new uniform for US teens and twentysomethings: checked shirts, grandad cardigans, long, unkempt hair and Converse trainers. Girls, meanwhile, had a new role model in Courtney Love, lead singer in grunge band Hole, Cobain’s wife and proponent of babydoll nighties worn with tough boots. It all fitted beautifully with the grunge/waif fashion from the UK, and my favourite portrait of Cobain remains the one taken by David Sims for the cover of the Face in 1993, showing the singer wearing a vintage floral dress.

The Seattle set wore the thick flannel shirts of lumberjacks and fishermen out of necessity: they were warm and they were cheap. But nothing says humble like a checked shirt, and for a good while after grunge broke out of Seattle, it also became the uniform of the hipper A-lister: Johnny Depp, Brad Pitt, Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix were rarely photographed without one, usually worn open with a T-shirt underneath and artfully ripped jeans.

For his spring/summer 1993 collection for Perry Ellis, US designer Marc Jacobs sent a grunge collection down the catwalk, featuring silk shirts printed with checked patterns, floaty chiffon granny dresses and models in Dr Martens and satin Converse trainers. “It was about a sensibility and also about a dismissal of everything that one was told was beautiful, correct, glamorous, sexy,” he recalled in a 2011 interview. “I loved that it represented a newness. I think that’s how people dress now. That moment hasn’t passed. It’s morphed into different things, but it really hasn’t passed.”

Perry Ellis famously sacked the designer soon afterwards and halted production on the collection. Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love were equally horrified. Jacobs had sent them samples of the collection and years later Love claimed that they destroyed it all. “We burned it. We were punkers – we didn’t like that kind of thing.”

In the end, of course, none of this did Jacobs any harm. He went on to launch his own eponymous empire in New York, as well as becoming creative director of Louis Vuitton from 1997 to 2013. Kate Moss became a supermodel and the new aesthetic of imperfect beauty moved into the fashion mainstream, the luxury brands quietly consolidating and spreading across the globe. In the end, the dominant story of 90s fashion was not grunge or a love of the second-hand, upcycled or hand-made – it was all about the brand.

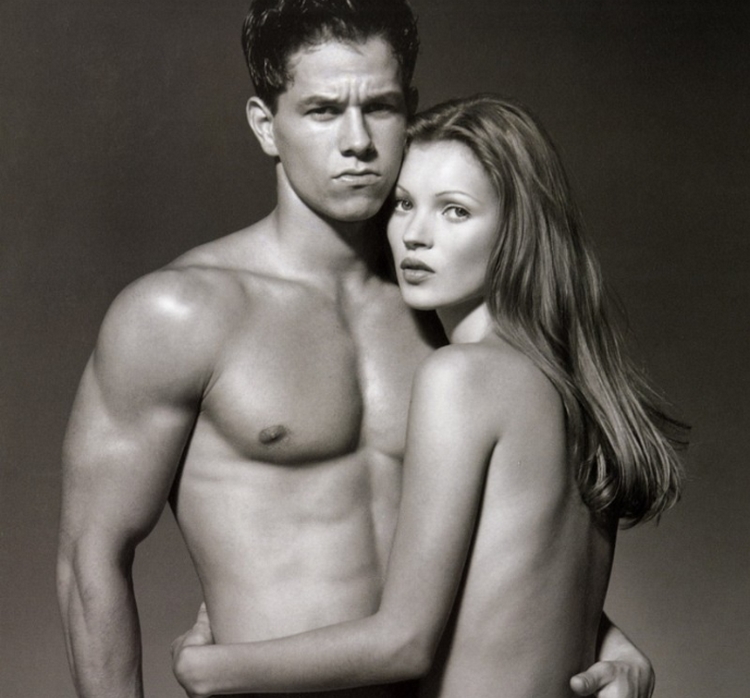

When Calvin Klein used Mark Wahlberg to sell his underpants in 1992, it was a controversial move for both sides. Now, it’s hard to find a luxury brand without celebrity ambassadors, and models have fought back by becoming brands themselves: launching their own clothing lines, perfumes and products. Even Courtney Love got co-opted in the end: by 1998, she was posing for a series of Versace ads, shot by Richard Avedon.

You can hardly blame her. We now live in a world where we’re all supposed to see ourselves as brands, forming strategic alliances with other brands. Former Spice Girl Victoria Beckham or former child actresses Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen have moved seamlessly into the luxury fashion market; Oasis bad boy Liam Gallagher has his own casualwear line, Pretty Green; and it seems there’s barely a celebrity alive without their own perfume range.

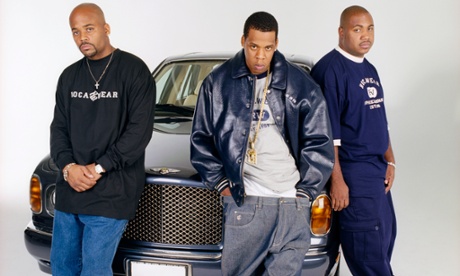

In this, as with so many things, hip-hop led the way. At the start of the 90s, rappers were wearing preppy, aspirational labels such as Calvin Klein, Polo Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger. By the end of the decade, US department stores were dominated by brands launched by the rappers themselves: Phat Farm, launched by Def Jam co-founder Russell Simmons in 1992; Rocawear launched by Jay Z and Damon Dash in 1999, and sold for $204m eight years later; Sean “Diddy” Combs’s labels Sean John and Enyce; and a host of others.

“I was in a Macy’s in San Francisco the other day, and there was Phat and Sean John and Ecko and Rocawear and Enyce and Shady,” Simmons said in January 2004, when he sold his company for a reported $140m. “Then in the corner, I saw Calvin and Polo. I didn’t see Tommy any more – all those brands have gone ice-cold.”

He was not knocking Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren or Tommy Hilfiger, he added: “I learned a lot from them.”

Sportswear is, of course, a huge influence on the urban brands, as it was on 90s fashion as a whole. From Air Jordan and old-school trainers to the Adidas stripe tracksuit top (near ubiquitous at the end of the decade); from the early 90s boom in skate/surf/hip-hop labels such as Stüssy, Mossimo and No Fear to our very own Sporty Spice telling us what she really, really wants in track pants and a cropped running top, clothing designed for athletes became a style statement, or at least a comfy outfit for lounging around in.

Fashion – like club culture – moves in cycles, borrowing from and building on what came before, as well as reacting against it. As a result, the trends of the 90s are never far away and will only get more dominant as the kids who came of age in that era now become art directors and creative directors.

The September issue of fashion maven Carine Roitfeld’s CR Fashion Book, for example, will also include her first men’s fashion book, with stories based on the style of 90s icons Kurt Cobain and River Phoenix. For Saint Laurent’s spring/summer 2016 menswear show, designer Hedi Slimane also channelled the ghost of Cobain, sending his models down the runway with long, unkempt blonde hair, round plastic sunglasses, ripped jeans, checked shirts and knitted beanie hats.

The short checked skirts popularised by Jennifer Aniston in Friends – a show that can never be underestimated in its global influence on 90s style – have also been making a comeback, along with spaghetti-strap slip dresses and skater-girl floral prints with clumpy boots. Even Dr Martens have been returning to fashionable feet – on the catwalk for Rag & Bone, for instance, and worn by the likes of Alexa Chung.

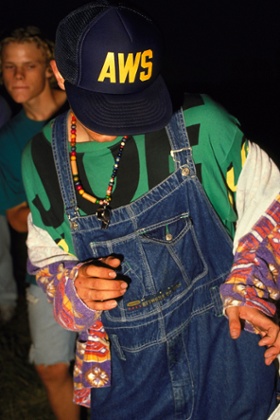

Dungarees – long derided as one of the never-to-be-repeated excesses of the E generation – are also, surprisingly, back with a vengeance. Glamour magazine’s website boasts a parade of more than 70 stylish celebs sporting them, including Alexa Chung again, Rita Ora, Sarah Jessica Parker, Rihanna, Lily Allen, Keira Knightley and Cara Delevingne.

What will not return, I fear, are trends that are rooted in a specific place. With MTV and then the internet disseminating new looks rapidly, and high-street stores copying catwalk collections before the original looks have even gone on sale, little stays unique or local for long. It’s hard to imagine something such as the 1990 Madchester baggy look – forged on the football terraces and in sweaty nightclubs of Manchester and Liverpool and popularised by Happy Mondays and Stone Roses – staying local for long now.

Tokyo has always been my favourite city for people-watching, with plenty of outlandish trends rarely seen outside of Japan. Last year, I sat in cafe in the young and cool Harajuku shopping district watching teenagers walk by – dressed, disappointingly, pretty much like teenagers anywhere else in the world. From Beijing to Birmingham, Mumbai to Manchester, you’ll find the same stores in the high street and in the luxury shopping malls, and the same looks.

That makes evolving a personal style – and sticking with it – all the more important. There’s a moment in the first episode of This Is England ’90 when Lol is trying to decide whether to go to a Madchester night with her friends. She worries that there won’t be time to go home and get a clean shirt. Her friend Kelly says she has some old Fred Perry shirts that she never wears any more, just like the one Lol has on. So Lol borrows a clean one, and goes out with the others, all dressed up in their rave gear. She looks great.

- This is England ’90 starts starts Sunday 13 September at 9pm on Channel 4

This article was amended on 8 September. The “upcoming European football tournament” should have been “upcoming World Cup”.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.