You can now use an app to summon a GP to your home, in the same way you would order a takeaway. We have come a long way since 1977, when a cardiologist named George Diamond pitched the idea of a primitive health app to predict heart disease to Steve Jobs. Jobs turned it down. Scroll forward to 2016 and there is a burgeoning field of what’s known as mHealth, medicine and public health supported by mobile devices. There are more than 165,000 mHealth apps in a market worth $489m (£346m).

What do they offer?

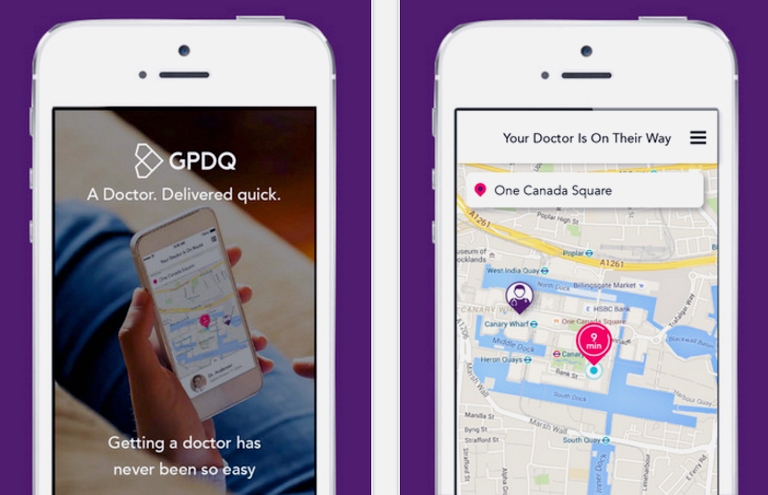

Health apps fall into several broad groups; the largest category relies on data that you enter about yourself, and provide nudges and information to help you make lifestyle changes. Others use data collected by a wearable device, such as a step counter. Some even use information from a sophisticated device such as an ECG heart monitor to provide diagnosis and management advice. The app that claims to deliver a doctor to your door is in a category of its own; it maintains a database of locum GPs prepared to do house calls in central London, for a price.

Do they work?

Apps can help to nudge us into maintaining a healthy lifestyle, but there is little evidence that they have lasting benefit. Inevitably, like diet books and gym membership, good intentions last only so long. Simon O’Neill of Diabetes UK says many lifestyle apps are “not very sticky” – people tend to use them for six weeks or so, then get bored, especially if they need to input data. Another potential problem is reliability – there is no sure way of knowing whether the information and advice is evidence-based and uses verified data. The NHS ran a pilot Health Apps Library to review and recommend apps using defined criteria, and it is being reviewed now. In the meantime, NHS Choices has a list of verified interactive tools, apps and podcasts.

Can they help to manage asthma?

Dr Samantha Walker, director of research and policy at Asthma UK, says some health apps to manage asthma are very helpful, but their quality varies: “Health apps have the potential to transform the way people with asthma manage their condition, from reminders to take their medicines to alerts regarding changes in weather, pollen or pollution levels. But reviews of current asthma apps on the market suggest that the quality is highly variable.” Walker says high-quality apps could have real benefit. “For example, if you use an asthma action plan, you are four times less likely to be hospitalised because of your asthma – but only 35% of people use one. A high-quality app that hosted a digital asthma action plan could have a huge impact, especially if it was also able to provide information directly into their electronic health record.”

Identifying migraine triggers

For migraine sufferers, an app can help to identify triggers and patterns and track responses to medication. Rebekah Aitchison, spokeswoman at Migraine Action, says that the traditional way of recording eating patterns and symptoms in a diary can be cumbersome. “Triggers can take 24 hours to cause a migraine. Apps allow the condensed information to be stored so you can show it to a GP quickly. Finding avoidable triggers is key; it may be getting enough sleep, eating patterns or a specific food. It’s not just a question of finding one tablet and bish, bash, bosh. And if you just Google migraine, which ranges from mild symptoms to ones that resemble a stroke, it can be very scary.” There are lots of migraine apps on the market, but the company behind Migraine Buddy worked with Migraine Action to develop its app.

Can they help to control diabetes?

People with diabetes need to know how much carbohydrate they’re eating – one app uses photographs of the food on your plate, recognises the portion size and what it is and estimates its carbohydrate content. Others enable you to input blood-glucose readings, food, exercise and medication and crunch the numbers to calculate what dose of insulin or drugs you need. As O’Neill, who has type 1 diabetes himself, points out, these apps have to be reliable – an error in insulin dosage could be critical.

Apps can also encourage behavioural change – children with diabetes often hate doing the blood test necessary to check sugar levels, so an app that links the test to collecting gold in a game has proved popular. But future developments may supersede the role of simple apps: devices that constantly measure blood sugar levels via a sensor on the skin will be able to “talk” to an insulin pump delivering a variable level of insulin into the bloodstream. However, O’Neill says this is is unlikely to be available before 2018.

What about heart problems?

The AliveCor is a mobile ECG recorder that can capture your heart rhythm. Many people experience short episodes of dizziness or palpitations that may have a cardiac cause, but without evidence, a GP may not be able to diagnose a serious problem such as paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) where the heart goes in and out of an irregular rhythm. AliveCor lets you record 30-second bursts by putting each hand on a plate the size of a 50p mounted on a base that fits on the back of your phone.

If you have PAF, says Francis White of AliveCor, you “may have a stroke on your journey to diagnosis”. The app lets you store information that your GP can act on straight away. AliveCor is approved by regulatory authorities in the EU and US as a medical device, which means it has passed stringent testing. White thinks this diagnostic end of the market is set to grow. “Home diagnostic tools will become like having a thermometer or set of scales in your home,” he predicts.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.