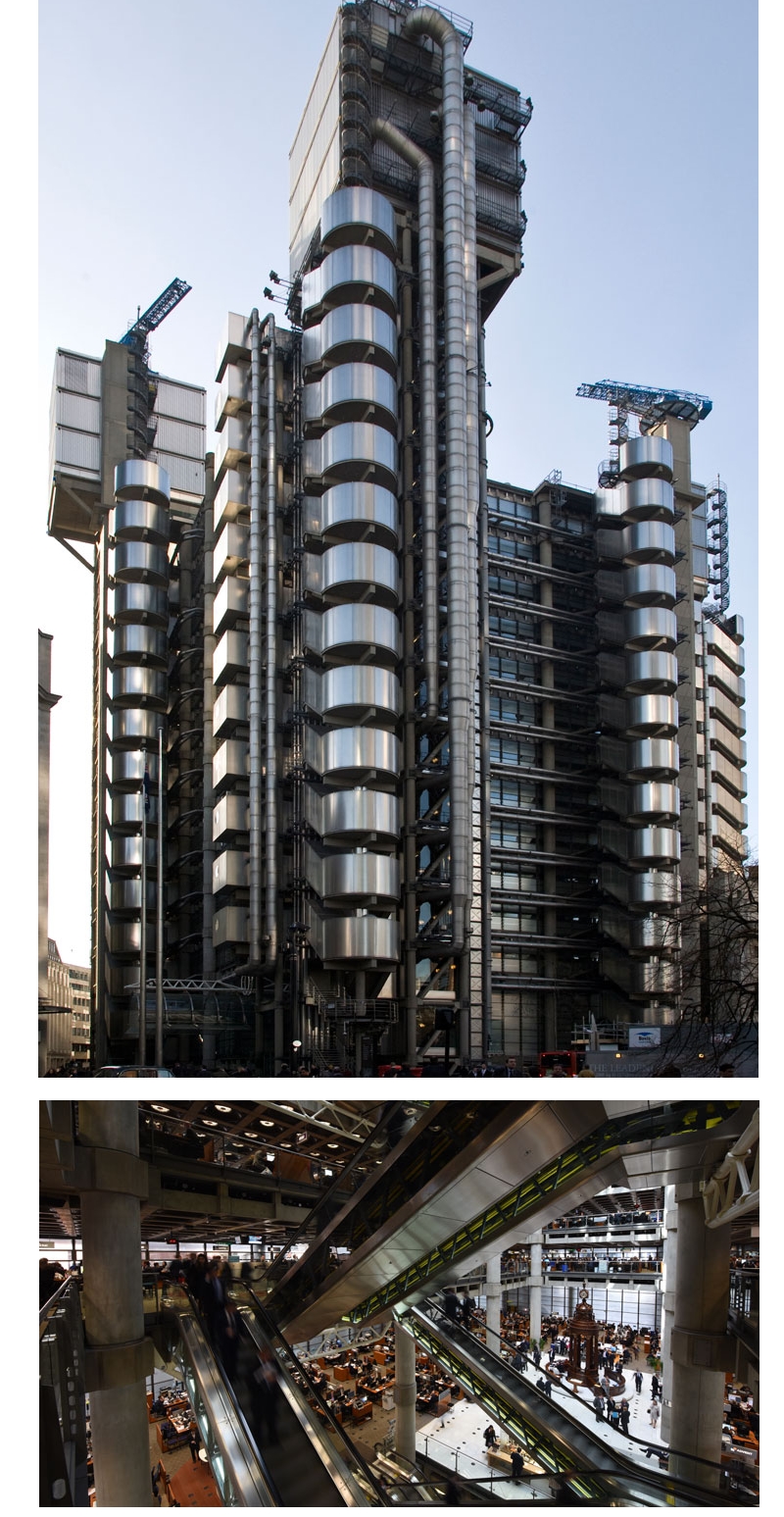

The internationally-renowned Lloyd’s building was designed by the architect Richard Rogers and took eight years to build. 33,510 cubic meters of concrete, 30,000 square metres of stainless steel cladding and 12,000 square metres of glass were used during the construction. @lloyds.com

Richard Rogers has never been the retiring type. He made his name with buildings that exploded their inner workings on to their outsides, dressing galleries and offices with rainbow symphonies of ducts and pipes. He became known for an equally colourful neon wardrobe, along with his love of public debate and bon viveur lifestyle. Now it seems the time has come for the 87-year-old architect to hang up his pencil: he is formally stepping down from the practice he founded more than 40 years ago.

Not that the pencil was ever Rogers’ favoured tool. He has always been, by his own admission, a terrible draughtsman, and he is dyslexic. He prefers to talk, ideally over a glass of wine and good Italian food. A tutor’s report from 1958 concluded: “His designs will continue to suffer while his drawing is so bad, his method of work so chaotic and his critical judgment so inarticulate.” Yet in his four decades in practice, and as an advisor to government, Lord Rogers of Riverside has probably influenced the face of urban Britain more than any other architect of the late 20th century.

He might be best known for his “inside-out” monuments to pipes: the magnificent Pompidou Centre in Paris and the still-thrilling Lloyd’s building in London. But his impact in the UK has been less about his own buildings and more to do with his influence on public policy, particularly under New Labour in the early 2000s. As chair of the Urban Task Force, he ushered in the era of regeneration that has seen UK cities adorned with canal-side apartments and cafe-lined squares, a vision of Barcelona street life transplanted to British shores, sometimes at a cost to existing communities.

His image of the “compact city” was presented as one of inclusivity and equality, but it would also foster greater displacement and division, producing a form of investment-fuelled development that has seen his own practice design some of the most expensive housing ever built in the UK. While the socialist Labour peer argued for a city for all, Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners were designing the fortified luxury apartment schemes of One Hyde Park, Neo Bankside and Riverlight, stacks of investment units that became symbols of London’s extreme inequality.

Although his name has always been above the door of the partnership, Rogers himself has had little to do with the office’s increasingly corporate work of the last decade or so. His early buildings remain by far the most compelling – perhaps none more so than his first major project.

Erupting like a psychedelic oil refinery in the middle of the Marais, the Pompidou Centre was a shock to Parisian tastes when it opened in 1977, and it is no less startling today. Designed with Italian architect Renzo Piano, it was conceived as a mechanical transformer of a building, a new kind of robotic architecture that would respond to changing needs, with plug-in components and moving floors.

Huge digital screens would entertain crowds on a great sloping piazza outside, while escalators in glass tubes would shuttle people up and down the building’s facade, forming a dynamic backdrop to the mime artists and musicians below. It was saturated with colour, its exposed pipes and ducts painted in the bright reds, blues and greens of the media age – a feature that would continue in Rogers’ work for years to come. The point, he said, was that “culture should be fun”.

It had a bumpy ride: the screens were dropped, the floors didn’t move and fire regulations curtailed some of the more daring ideas. Pressure groups filed lawsuits against the project, while a Guardian art critic said the “hideous” object should be covered with virginia creeper. But the architects were vindicated by the public reaction: around seven million people visited in the first year, more than the Louvre and Eiffel Tower combined. The building set the mould for museum galleries to be conceived as gigantic flexible containers and it provided a premonition of the city-boosting statement cultural architecture that would be at the top of every mayor’s shopping list for years to come.

The French tanker of art also set the aesthetic and ideological agenda for Rogers’ practice. Structure would be exposed – and jauntily painted – and express what it was doing, in as didactic a way as possible. The ambition was to make buildings lighter and more flexible, to minimise structure while maximising space and light, and reduce demands on energy and the natural environment, in pursuit of a technological sublime.

In London, the sculptural potentials of this hi-tech age were first proven in the new HQ for insurance giant Lloyd’s of London, completed in 1986. With floors clustered around a 60-metre high atrium, lit by a barrel-vaulted glass roof, its most radical move was to place the service cores outside the building in a series of towers. This freed up more floor space for desks, and let Rogers revel in the dynamic interplay of staircases, glass lifts and toilet pods on the facade, in a polished frenzy of stainless steel.

Twenty-seven years later, the firm would explore the same ideas across the street, in steroidal form, with the Leadenhall building. Nicknamed the Cheesegrater, its services are again shuffled to one side to free up floorspace and create an animated ballet of lifts on the facade – almost three times the height of Lloyd’s. In a nod to Rogers’ many pronouncements on the importance of public space, the tower was jacked up on 30-metre-tall legs to free the space below, although the resulting plaza feels more like a high-security open-air lobby.

None of his designs have quite matched the visceral thrill of the Pompidou or Lloyd’s, but Rogers continued to produce elegant and engaging public buildings, from law courts in Bordeaux and Antwerp to the National Assembly in Wales, where an image of transparency and public accessibility were always central. His tensile white tent for the Millennium Dome, while ridiculed at the time, has gone on to house one of the most successful live performance venues in the world, as the O2 Arena.

My favourite is Rogers’ terminal for Madrid-Barajas airport, for which he won the Stirling prize in 2006. It is rare for an airport terminal to be a place you might actually want to stay for a while, rather than escape as soon as possible. With its undulating bamboo roof floating above an avenue of branching rainbow-coloured columns, it is a calming place that soothes the stress of international travel. It took just eight years from conception to completion, a stark contrast to his practice’s scheme for Heathrow Terminal 5, which was subjected to the longest public inquiry in British history and took 19 years to be built. As a result, it seemed outdated by the time it opened.

It might be unusual for an architect of Rogers’ stature to retire, but it is fitting with his character that he should want to spend his final years enjoying himself, rather than stuck in the office. I first encountered him while working at London’s City Hall in the mid-2000s, when he was chief adviser on architecture and urbanism to then-mayor Ken Livingstone. Rogers would come in every now and then to review our work, and occasionally take the team out for a boozy lunch. I remember offering him some water one lunchtime, at which he looked aghast. “I don’t drink water,” he exclaimed with a beam, clutching a glass of white wine in one hand, and a glass of red in the other. “Fish fuck in it.”

• This article was amended on 1 September 2020 to clarify elements of the design of the Lloyd’s building.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.