Black and gold: (from left) Sheikha Raya Al-Khalifa, Elham Al Ansari, Shareefa Fadhel, Farheen Allsopp and Fathiya Ahmad Al Jaber. Photograph: Suki Dhanda for the Observer

When Sheikha Raya Al-Khalifa moved from her home country of Bahrain to Qatar a few years ago to marry her husband, her friends were anxious.

“They immediately said: ‘Oh no, you’re going to a country where you’re going to wear the abaya!'” recalls Sheikha Raya, laughing at the memory.

We are sitting in the lounge of a luxury hotel in South Kensington, London, sipping on glasses of iced water. Sheikha Raya is draped from head-to-toe in a black abaya. Her hair is covered but her face is visible and impeccably made-up. Her nails are painted bright red. A chunky gold necklace hangs from her neck. Her 4in heels are Valentino “Rock Stud” pumps.

Despite her choice to dress in a garment associated with religious and patriarchal subjugation, the 29-year-old Sheikha Raya does not in any other respect look like an oppressed woman. “When people make comments about ‘covering up’, they’re not understanding,” she says. “It’s not this forced-upon-us thing. It’s a reflection of what is part of our culture.”

Sheikha Raya is one of a new wave of young women across the Middle East and beyond who are seeking to redefine traditional Islamic dress – the abaya (cloak), the niqab (the face veil), burqa (whole body covering) and the hijab (the head and shoulder scarf) – as a means of female expression. These women insist that they do not equate modest dressing with persecution, but that wearing an abaya can be a statement both of individual choice and style.

It is a stance that continues to divide opinion. In September, the deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, ignited a national debate after saying he did not think the full veil was appropriate attire for airport security or the classroom. Shortly afterwards, a government review was launched into health-service guidelines on veils to ensure that patients had “appropriate face-to-face contact”.

At the same time as the politicians were debating the issue, the Victoria and Albert Museum hosted a high-gloss event on the eve of London Fashion Week to showcase the work of three female Qatari designers, all of whom took the traditional Islamic dress as their starting point. On the catwalk, richly embroidered abayas were teamed with futuristic Philip Treacy headdresses and Asprey handbags.

Farheen Allsopp, a businesswoman and former model who co-ordinated the Fashion Exchange initiative, says the aim of the event was: “To celebrate the abaya as a garment of style and modesty much like the kimono and sari have been with Japanese and Indian cultures. In my view, the abaya is a garment of expression rather than of oppression.”

She gestures to her own chic outfit: a sheer black abaya worn over American Apparel leggings, Sergio Rossi heels and cinched in at the waist with an Alexander McQueen belt.

“I am wearing it as a gown and it’s not about showing skin, it’s about showing how elegantly you carry something,” she says. “You can use different fabrics, different silhouettes.”

Both Sheikha and Farheen insist they are increasingly frustrated by the “patronising” western attitude that assumes a woman must be incapable of acting assertively if she is wearing the abaya or the niqab. “Just because we wear the abaya, we’re not sitting at home doing nothing,” says Sheikha. “Don’t get us wrong.”

It’s a point of view that leaves many in the west feeling distinctly uneasy. And the notion of the abaya or niqab as a fashion statement still has the capacity to provoke enormous controversy.

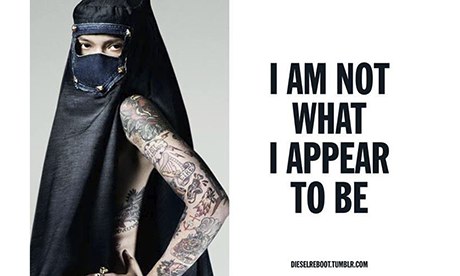

When Nicola Formichetti, the artistic director for clothing label Diesel and Lady Gaga’s former stylist, developed a recent advertising campaign featuring a tattooed woman wearing a niqab and nothing else alongside the tagline: “I am not what I appear to be” there was an outcry.

“The key issue is whether a woman is required to wear the abaya by law,” says Leila Ahmed, a professor of divinity at Harvard University and the author of A Quiet Revolution: The Veil’s Resurgence, from the Middle East to America. “If they are free to choose, you could certainly argue the bikini is no more sexist than the abaya: they are both constructions of the female body.”

Of course, in less repressive states such as Qatar and Dubai, women are more able to make their own choices than in, say, Saudi Arabia, where the strict dress code requires a woman to show only her hands and eyes. But even if something is not enforced by law, can wearing the abaya or the niqab ever truly be an act of empowerment?

In her bestselling feminist memoir, How to be a Woman, Caitlin Moran claims the idea of choosing to wear a veil is an illusion. “Who are you being protected from?” she writes. “Men. And who – so long as you play by the rules, and wear the correct clothes – is protecting you from the men? Men. And who is it that is regarding you as just a sexual object, instead of another human being, in the first place? Men.”

But Professor Ahmed argues that female clothing from all cultures, religions and ideologies, has some kind of sexist underpinning.

“I think all dress is symbolic and often very sexist in most societies,” she says. “It is true that the abaya keeps the male gaze away. I think in other eras it was one of the explanations why western men who first went to Muslim societies were so offended by it, because they couldn’t see the woman underneath; they didn’t have access to women’s bodies.”

In Paris, an underground graffiti artist called Princess Hijab has taken to the streets in recent years and spray-painted veils and hijabs over fashion models depicted on advertising billboards. The question implicitly being asked is whether hiding a face behind a niqab is any different from hiding one behind make-up and air-brushing in a high-gloss poster celebrating consumerist mores.

Indeed, Sheikha Raya insists that wearing the abaya in the name of style actually removes the need to be competitive with other women about appearance or designer labels. It is, she claims, an egalitarian garment that can be liberating simply because you don’t need to think about different outfits throughout the day.

“I take my child to school at 6am, I do my errands, I get an unexpected call to go to a business meeting, I have a formal dinner at the end of the day and for all of which I’m wearing my abaya,” she says. “If you’re in the west, you have to go and change or do your hair. I think the latter is more of a restriction.”

With the emergence of the Gulf States as economic centres, a new wave of designers is already seeking to capitalise on their spending power. In 2011, Reuters reported that women from the Middle East have become the world’s biggest buyers of haute couture.

Riccardo Tisci at Givenchy did a 2009 collection based on Bedouin robes and traditional Arabic headgear while Alessandra Rich, a British designer whose creations have been worn by Samantha Cameron, used a series of her high fashion abayas in a photoshoot for Vogue Italia.

Many of Valentino’s autumn/winter haute couture gowns display a distinctly Islamic influence (including a floor-length, long-sleeved agate and chartreuse gown) and the designer Stephane Rolland famously has a vast client base across the Middle East – in August, he opened his first pret-a-porter boutique not in Paris, Milan or London but in Abu Dhabi.

In 2010, the same year that the French government banned the veil, Chanel’s creative director Karl Lagerfeld praised the burqa because: “I find it picturesque.” A year later, when Nigella Lawson went swimming in Sydney sporting a burkini (swimwear originally designed for Islamic women), sales of the item rose by 400%. Lady Gaga often wears items of Islamic dress on stage – including a neon pink burqa.

The women I speak to argue that simply because they might choose to dress modestly does not automatically suggest they are not fashionable, nor does it imply a disapproval of more revealing clothes – it is still possible for a woman to wear as little as she likes and not to deserve objectification or misogyny. In fact, many Islamic feminists argue that endlessly debating the worthiness or otherwise of wearing the veil or the abaya dehumanises the individual woman and detracts attention from more pressing issues such as jobs and education.

Can an abaya or a niqab ever be separated from its religious heritage and viewed purely as a fashion statement? Sheikha Raya points that the Gulf state economies have grown rapidly over the past few decades as the oil industry has expanded. Consequently, the region: “has had to modernise very, very quickly, in a fraction of the time it took the rest of the world.”

The suggestion is that, although the economy might have undergone a fast-paced change, cultural and religious history will take some time to catch up.

“I grew up in America, where women didn’t get the vote until the 1920s,” explains Sheikha Raya. “In the west, women are still not being paid an equal wage. Maybe we should look at this gender inequality as a global issue rather than concentrating on what people are wearing in their own culture. Because we’re happy. We’re definitely not oppressed.”

That might not mean much to the woman in Saudi Arabia who is forbidden from learning to drive or the schoolgirl in Pakistan who is shot in the head purely because she wanted an education. But what voices like Sheikha Raya, Farheen Allsopp and Leila Ahmed are saying is that the debate shouldn’t just be about a veil or a cloak. It should look deeper.

“I think the whole issue of ‘Islamic feminism’ is very complicated because it tends to erase [the fact] that Muslims are like other people,” says Professor Ahmed. “They might be secular, they might be very religious, they might wear the hijab or not. There are the same kind of issues if you are a Jewish feminist or a Christian feminist or a Muslim feminist.”

A woman, then, is more than just the clothes she wears or the fashions she chooses to follow. That goes for any culture – with or without the blinged-up abaya.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.