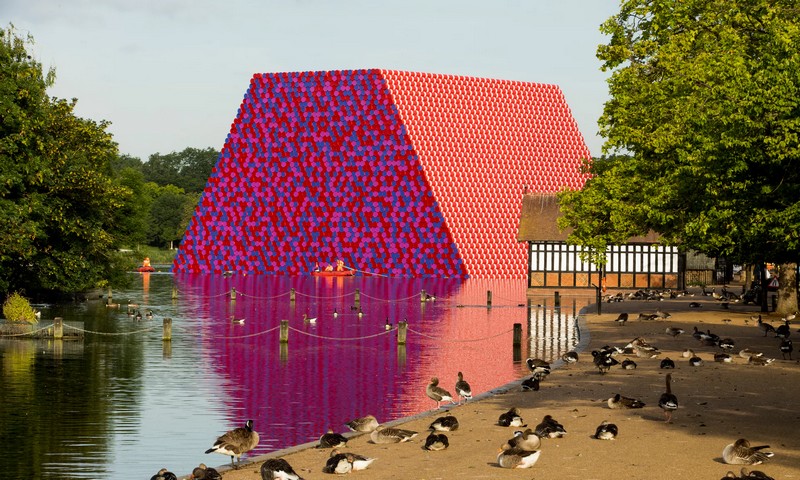

The London Mastaba by Christo, on Hyde Park’s Serpentine lake. Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian

“All interpretations accepted”: so said Christo at the launch of his floating sculpture on the waters of the Serpentine lake last week. Given its shattering size – about three times the height of a three-storey house – it’s amazing that this multicoloured object appears to float so lightly. A trapezoid with two vertical and two sloping sides, soaring up to a flat top, it is constructed out of 7,506 barrels painted red, blue and mauve and attached to an invisible structure. You are meant to gasp. Any additional response is frankly a plus.

Artist of the Wrapped Reichstag and the Colorado Curtain, in which 400 metres of orange cloth was strung among the Rocky Mountains, Christo is addicted to scale. The Serpentine Gallery show that accompanies this muckle polyhedron is stuffed with drawings and models for unrealised projects that would dwarf the Colossus of Rhodes. A further version of the London Mastaba, as it’s called, designed for the deserts outside Abu Dhabi, would be almost six times larger – the biggest sculpture in the history of the world.

It hasn’t happened yet, any more than the silver curtains that Christo, along with his late partner Jeanne-Claude, aimed to float down the Arkansas River; or their scheme for wrapping the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At 83, the artist still lives in hope, along with his legions of fans. Like Deadheads, these followers travel the world to take in Christo’s wonders: the mysterious “bridge” between two Italian islands that allowed visitors to walk on water, as it seemed; the wrapping of the Pont Neuf in golden fabric; the flame-coloured banners that blazed through New York’s Central Park in 2005.

This is art as public event: a shared experience for every citizen. Christo is nothing if not democratic. Born in Bulgaria in 1935, he escaped the Soviet Bloc for Paris at the age of 20, eventually reaching New York. His is a utopian philosophy in which art is to bring joy (and thought) to each and all. He pays for every project himself, so there is no state or private involvement; and no project ever lingers. This one will be gone by September.

Which may be good news for the Serpentine swimmers forced to navigate the incredible hulk each morning, the dog walkers who cannot stand its vivid colours, the pleasure-seekers who find their boats overshadowed by its monumental presence. And it may be bad news for those who love the cognitive dissonance of an aggressively contemporary sculpture, in all its high-chrome abstraction, in the midst of cultivated nature.

The very least that can be said of it is that it is designed to divide. This is a function of scale and colour, first to last. If the Mastaba was small, it would be trivial but pretty. If differently coloured – in silver, say – it might carry the ever-changing effects of light in far more compelling ways. With a pointed tip, it would resemble a pyramid. With a golden elephant on top it would mean something totemic, ancient, mysterious (a mastaba is a kind of Egyptian burial tomb). But instead it is a purely abstract form got up in modern colours and taken to super-sized limits.

This is an environmental piece, like all of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work. So of course it performs according to the atmosphere. Two sides are an abrasive scarlet, each barrel painted with nautical white stripes; they don’t alter much. But the other sides swarm with coloured discs like a vast pointillist painting, reflecting blurred and shifting hues on the water. Alas, this pleasure is short-lived.

Some people say the barrels invoke current oil politics, but this seems doubtful. Almost every object in the Serpentine show is composed of barrels, stretching back 50 years and including early pastiches of modernist sculpture. And here is a central aspect of the London Mastaba: it is only one of many. Nothing unique, nothing relating to London, politics, culture, the landscape or the times – just another edition, gigantic, deflective and inert. Interpretation is not just a stretch; in this case, it feels entirely unnecessary.

Go instead, if you can, to Tomma Abts’s marvellous show of paintings up the road at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, each one a perfect enigma. The German-born Abts won the 2006 Turner prize for her abstract canvases; small, exquisitely painted and utterly singular. Not one is like any of the others.

A ribbon of changing colour flutters around a bright rectangle, threading its way in and out of space so that the eye cannot see its beginning or end, or even pick out its exact journey. A sunray form, something like a paper fan, casts an impossible light as well as vivid shadows. The brilliant stripes running down one surface suddenly seem to sheer away on their own, as if trying to detach themselves and exit the picture altogether. The eye is captivated by what the mind can hardly fathom.

Metallic paintings reflect but somehow deny the world around them too. Surfaces are scraped, polished, divided and embossed, sometimes all in one picture, so that one has the strongest sense of its cumulative making. Arrays of sharp lines, discs and angular shapes appear on the verge of locking into a gorgeous pattern, but always dance lightly away. There is an extraordinary animation that isn’t just the legacy of op art, hi-fi illusion or trompe l’oeil. Some paintings look as if they might be susceptible to opening out like a window or unfolding like complex origami.

Each has a title that sounds like somebody’s name (Fimme, Zebe, Sierk). And certainly all have a distinctive character – brisk or evasive, unstable, witty, reticent or vivacious – that seems to suggest a living personality. In this show, there are paintings evocative of flags, searchlights, shuffled playing cards and even (it seems to me) figures dancing the charleston. And with metaphor comes a kind of lyrical philosophy, to the effect that no painting seen or made by human beings can ever be wholly abstract.

Star ratings (out of 5):

Christo: London Mastaba ★★

Tomma Abts ★★★★★

• Christo’s London Mastaba is at the Serpentine Gallery, London W2, until 9 September

• Tomma Abts is at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London W2, until 9 September

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.