Paris-based artist Nadine Rotem-Stibbe explores environmental issues with a keen eye for design. Her installation In Loving Memory, 2018, 0.8°C, a collaboration with Ryan Cherewaty, can be found at an abandoned building site at the Ebbingekwartier of Groningen, the Netherlands. images: nadiners.com/lovingmemory.php

In 1975, photographer Michel Comte stood up before scientists, business leaders and politicians at the Club of Rome to deliver a speech about the climate disaster he believed was on the horizon. Back then, he was still a student, and a little nervous – but he could sense the future. Now, Comte’s recent works incorporating black carbon fallout from the jet stream, shown in Rome, Milan and Hong Kong, prove just how right he was to speak out.

Comte’s message was echoed last week in the UK, when thousands of schoolchildren – inspired by 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg – took to the streets to pressure the government into taking action on climate change. Like Comte, they have seen a bleak future ahead and are speaking out.

Sadly, that hasn’t been the case for most artistic and cultural institutions, which have spent the last few decades responding to climate change with little more than silence. They have been dangerously complicit in desensitising society to what’s really at stake.

It hasn’t always been this way. In the mid-90s, when a post-Chernobyl generation made its voice heard, the ecological protest movement was nurtured by critical theatre, radical art shows, public debate and avant garde music. Then something changed. In response to the backlash against fossil fuels, major energy suppliers became involved with arts sponsorship. This was no harmless philanthropy. Parallel to the rise of the blockbuster exhibition the importance of Shell and BP to the artistic budget of arts centres grew, to a point where many major national institutions were on the payroll of the fossil fuel giants. Some still are today.

But even for those who have freed themselves of it (or exchanged them for carmakers), the damage to a generation has been done. For decades arts institutions have effectively engaged in self-censorship to pay for their productions, putting on amazing programming and covering critical topics, as long as it wasn’t a thorough debate of our addiction to fossil fuels. This strategic exclusion of a topic from public debate over more than a generation has led to ignorance, with repercussions in education, academic and public life.

But there is hope in the air. Tate Modern have an Olafur Eliasson retrospective scheduled for this summer – his Ice Watch project was recently invited to melt away outside the museum, with the carbon impact of each block accounted for. As for Comte, he is about to board a sailing boat for a challenging passage to the Arctic, creating a monumental light installation calling for us to change our ways before it’s too late. If we allow more artists such as these to become part of the conversation, we will have a culture fit for the generation of children who took to our streets.

Nuclear fallout, rising sea levels and … nail clippings

When artist Yi Dai opened her first solo show in Berlin, she received rapturous reviews praising her subtle and intelligent coverage of environmental topics. Misfits, Offcuts and Castaways, in 2016, was an urgent statement reflecting on the aftereffects of nuclear fallout and rising sea temperatures, and the fragility of our ecosystem. Her exhibition was as much a personal account of her experience on the Marshall Islands as it was a call to action following the then-warmest winter in recorded history. Her show, Discarded… During My 20s (at House of Egorn in Berlin until 23 February), explores the subject of the human body: the artist juxtaposes bodily remains – hair, nail clippings, blood – with construction materials such as steel, concrete and glass that surround, contain, or reflect our bodies.

Sailing to the Arctic for a climate vigil

Wavelength Foundation was formed on a sailing boat in late 2017 by an international group of journalists, writers, environmentalists, cultural workers, artists and scientists. One of the foundation’s fundamental principles is that a rich and meaningful cultural engagement with nature is needed to readjust their lost relationship. Comte will soon set sail to the Arctic with the foundation for his large-scale 3D-mapping light installation Black Light, inviting sailors from around the globe to join his monumental climate vigil. Meanwhile, the foundation’s Change Maker scheme is helping to build a sustainable arts and culture centre in South America, to bring the opportunities of a circular economy to the lives of children and younger people looking to escape the cycle of poverty.

Remembering Earth before the cataclysms

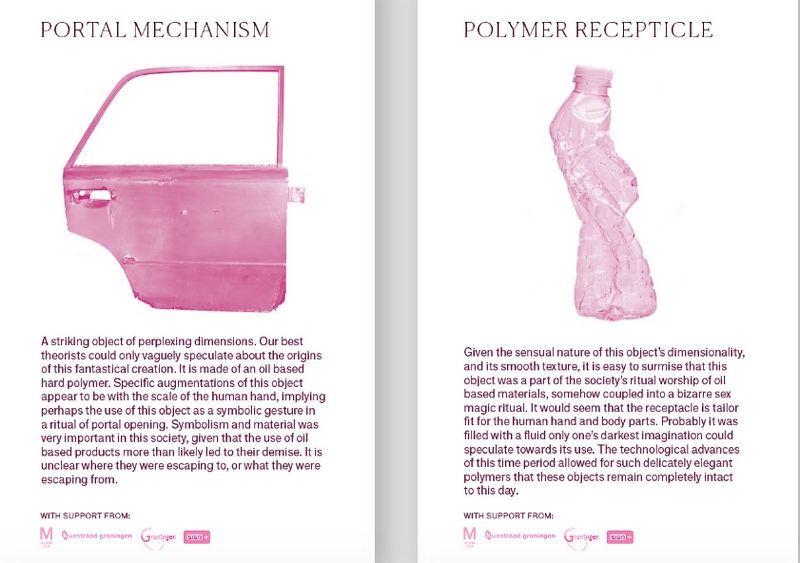

Paris-based artist Nadine Rotem-Stibbe explores environmental issues with a keen eye for design. Her installation In Loving Memory, 2018, 0.8°C, a collaboration with Ryan Cherewaty, can be found at an abandoned building site at the Ebbingekwartier of Groningen, the Netherlands. It takes a part mocking, part melancholic view of our time, looking back from a fictitious (yet by no means unrealistic) future in which a large cache of archaeological objects has been uncovered in the Trans-European floodplain. The artefacts offer an unprecedented look into human life in 2018, prior to the great cataclysms that struck. There is a profound obsession with objects created from the industrial processing of complex carbon-chain polymers – plastics – an industry that was a key factor in heavily increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. These objects seem to have survived extreme climate changes and offer a glimpse into our perplexing culture.

The art school on the edge of the world

Perched on the shore of a sea loch and overlooking the Minch and the hills of Harris and Skye, Lews Castle College in the Outer Hebrides has been referred to as the “art school on the edge of the world.” Sustainability is a key element to the teaching, with students responding to the environment and the unique wilderness of the unusual location. The college hosts talks from practitioners across a range of areas, from marine biologists and archaeologists to traditional makers working with natural materials. Part of the college building is the site of a recently commissioned light installation by Finnish artists Timo Aho and Pekka Niittyvirta, which interacts with the tidal changes, activating on high tide. The work provides a visual reference of future sea level rises and explores the catastrophic long-term impact of our relationship with nature.

Mountain biking through our tumultuous weather

Tales of Change brings together stories of how climate change is impacting communities in some of the planet’s most iconic mountain ranges. Its protagonist, Florian Reber, cycled across the Alps, starting in Trieste on the Adriatic coast and arriving in Cannes, at the Mediterranean Sea. Along the way, he talked with farmers, foresters, conservationists, tourism experts, alpinists and professional athletes, psychologists, writers and journalists about climate change. Periods of tumultuous weather extremes are the consistent findings, including a pronounced drought that left many rivers and sources in the southern Dolomites dried out. This was followed by the strongest föhn storms in recent years, causing record temperatures in October 2018. Next came torrential rain and strong winds brought about by cyclone Vaia, uprooting thousands of trees and causing casualties. While this trip involved cycling 1,180 miles, climbing more than 35,000 vertical metres and mastering two dozen mountain passes in winter, the intrepid explorer is now getting ready to widen his reach towardsthe Rocky Mountains and Himalayas. The project has been on display in Switzerland and Italy but, like Reber, is constantly moving.

Solar robots transforming snow back into glaciers

Housed in Barcelona’s magnificent historical pavilion Sant Cosme y Sant Damià, Quo Artis is an international non-profit organisation dedicated to advancing the dialogue between arts, science and technology. Recent activity includes Glaciator, an art installation in Antarctica composed of solar robots that help to compact and crystallise the snow by turning it into ice, then adhering it to the glacier mass. As glacial melting is one of the most alarming effects of global warming, the mission of these robots is to accelerate the ice formation process, allowing glaciers to regain the mass they have lost as a result of the thaw.

The old furniture factory where ‘waste is a failure of the imagination’

This 1930s furniture factory, in southern Sweden, is being turned into one of the most exciting places for interdisciplinary research and innovation in sustainability. The brainchild of former gallerist David Risley, the hub brings culture together with science, philosophy, free thinking and business, and is scheduled to open in summer 2020. With more than 12,000 square metres of open-plan space set over several floors, Funkisfabriken could become a test bed for new sustainable approaches. “Waste is a failure of imagination,” reads its founding slogan. Located a short walk from the botanist Carl Linnaeus’s house and garden, the space will feature an array of labs (wet, dry, clean and dirty), an urban farm, a circular economy centre, and conference facility, exhibition spaces and sculpture parks – not to mention a hotel, indoor garden and a zero-waste restaurant set up by Doug McMaster of the Brighton restaurant Silo.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.