Plastics have shaped our daily lives like no other material: from packaging to footwear, from household goods to furniture, from automobiles to architecture.

Maison Auguste Bonaz, brooches made from galalith and silver plated lucite, c. 1920-30; © Vitra Design Museum, photo: Andreas Sütterlin

A symbol of carefree consumerism and revolutionary innovation, plastics have spurred the imagination of designers and architects for decades. Today, the dramatic consequences of the plastic boom have become obvious and plastics have lost their utopian appeal. The exhibition “Plastic: Remaking Our World” at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany will examine the history and future of this controversial material – from its meteoric rise in the twentieth century to its environmental impact and to cutting-edge solutions for a more sustainable use of plastic.

The Vitra Design Museum numbers among the world’s leading museums of design.

Exhibits will include rarities from the dawn of the plastic age and spectacular objects of the pop era as well as numerous contemporary designs and projects ranging from pragmatic product innovations to solutions for cleaning up the oceans and bioplastics made from algae or mycelium.

The exhibition begins with a large-scale video installation spotlighting the conflicts linked to the production and use of plastic. Timeless images of unspoilt nature are juxtaposed with film documents from one hundred years of plastic industry that impressively convey the ambiguous fascination of increasingly fast-paced automated production at rapidly diminishing costs. The formation of fossil resources such as coal and oil took more than two hundred million years, while the synthetic materials made from them needed little more than a century to become a problem of planetary scale. An invention that promised to democratise consumption gave rise to a frenzied throwaway culture that threatens our global environment.

The second part of the exhibition follows the evolution of synthetic materials from the mid-nineteenth century to the present.

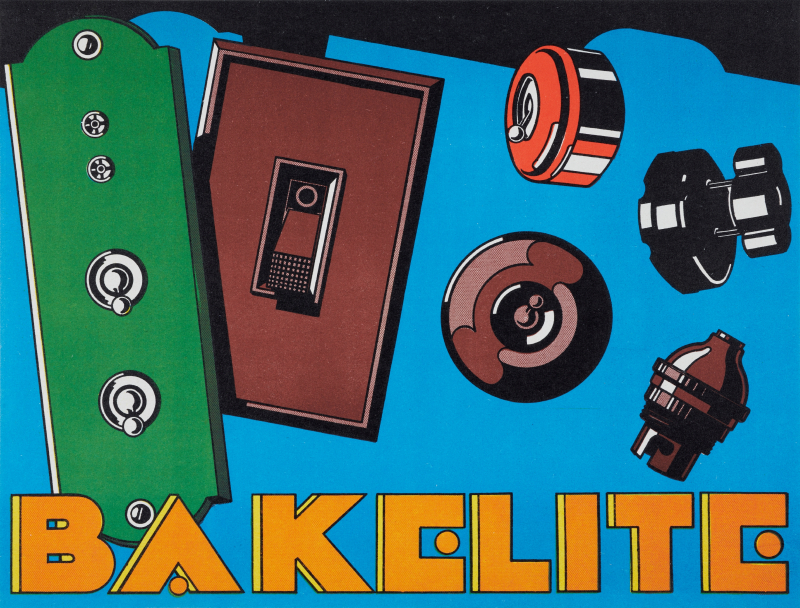

It looks back at the emergence of the first plastic materials, many of which were plant- or animal-based. Gutta-percha, for example, a material used for decorative objects and insulation for underwater telegraph cables, was made from the latex of certain trees, while the shellac from which the first gramophone records were pressed is a resin secreted by scale insects. Early plastics are closely linked to colonialism as Western European colonial powers exploited the forests of Africa and South East Asia to obtain the natural resources they required. The first plastic made from purely synthetic components was invented in 1907 by Leo Baekeland, named Bakelite, and hailed as a material of unlimited opportunities.

Petromodernity

Being nonconductive, it was ideal for light switches, wall sockets, or radio sets and played a central role in the electrification of everyday life. While early plastics were often developed by independent inventors, from the 1920s onwards the expanding petrochemical industry took a leading role. This marked the beginning of an era of »petromodernity«. Developments in the field of plastics were catalysed by the Second World War, which led to materials like Plexiglas – for aircraft canopies – or Nylon – for parachutes – to be processed on a large scale.

Post-1945, these materials found new, domestic uses in plastic cups and plates, Tupperware, toys like Lego and the Barbie doll, or the coveted Nylon stockings. A few years later, a growing fascination with space flight shifted the focus to plastic’s utopian potential, which was reflected in futurist shapes and new interior design concepts. Examples on display in the exhibition include Eero Aarnio’s »Ball Chair« (1963), Gino Sarfatti’s »Moon Lamp« (1969), and the »Toot-a-Loop« (1971), a plastic bracelet with a built-in radio.

The oil crisis in 1973 meant lower supplies and higher prices for the resource from which most plastics were made, but it had little long-term effect on the plastic boom. While global plastic production soon picked up again, strategies for reducing or recycling plastic were slow to emerge.

In the 1990s, designers like Janeat Field began to develop a new aesthetic based on recycled plastic. This also drew attention to the great variety of materials broadly covered by the term »plastic« – an infinite spectrum with a wide range of different qualities which have to be carefully considered in recycling processes.

Meanwhile, the issues arising from the plastic boom have etched themselves in our collective consciousness: from microplastic in the soil, in the oceans, and in our bodies to mountains of packaging waste that are often disposed in countries of the Global South – with massive ecological consequences.

The Ocean Cleanup, system 002 deployed for testing in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, 2021; © The Ocean Cleanup

So what do we need to change? How can we overcome the global plastic waste crisis? And what role can design – alongside industry, consumers, and politics – play in the process?

These are the questions addressed in the third part of the exhibition. It presents projects like “The Ocean CleanUp“, “Everwave”, or “The Great Bubble Barrier”, which were developed to filter plastic waste from rivers and oceans, but it also makes clear that an effective reduction of plastic waste must start at a much earlier point. Reducing packaging and single-use products requires a circular design approach that takes account of an object’s entire life cycle. An example for this is the “Rex Chair” (2011/2021) designed by Ineke Hans, which can be returned to the manufacturer for repairs or recycling.

Meanwhile, the ordinary plastic drinking bottle serves as a case study to show that reducing the high quantity of single-use plastic requires a combination of infrastructures – in this case, deposit-return schemes, adapted production facilities, and alternatives such as drinking fountains.

An exhibition satellite in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery sets a special focus on recycling and offers an interactive space where visitors can learn about different types of plastic and recycling systems. It is centred around the “Precious Plastic”project initiated by Dave Hakkens in 2013, which illustrates how plastic waste can be turned into a valuable resource. Today, many scientists and designers are going back to exploring materials that are based on renewable rather than fossil resources and often referred to as bioplastics. The exhibition presents experiments with algae by Dutch designers Klarenbeek & Dros, research on mycelium at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, and a variety of projects dealing with other promising technologies.

The British start-up company Shellworks, for example, harnesses microorganisms to create plastic, while the University of Portsmouth and ETH Zurich are both testing enzymes for plastic degradation.

As a whole, the exhibition »Plastic: Remaking Our World« offers a reassessment of plastic in today’s world that is both critical and differentiated. Interviews with designers, scientists, and activists underline the importance of an interdisciplinary approach in which politics, industry, science, and design collaborate closely to tackle the plastic problem.

While it is true that each of us is a catalyst Vitra Design for change, there will be no simple remedy to this issue. For this reason, the exhibition aims to address the bigger picture of plastic and its complex role in our world: by analysing how we came to be so dependent on plastics, by showing how we can change this, and by reimagining possible futures for this contested material.

After its presentation at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, the show will travel to the V&A Dundee (29.10.2022 – 05.02.2023) and maat, Lisbon (Spring 2023).

The Vitra Design Museum is a privately owned museum for design in Weil am Rhein, Germany. Former Vitra CEO, and son of Vitra founders Willi and Erika Fehlbaum, Rolf Fehlbaum founded the museum in 1989 as an independent private foundation.

PLASTIC REMAKING OUR WORLD

26 March to 4 September 2022, Vitra Design Museum

An exhibition by the Vitra Design Museum Germany, V&A Dundee, and maat, Lisbon.