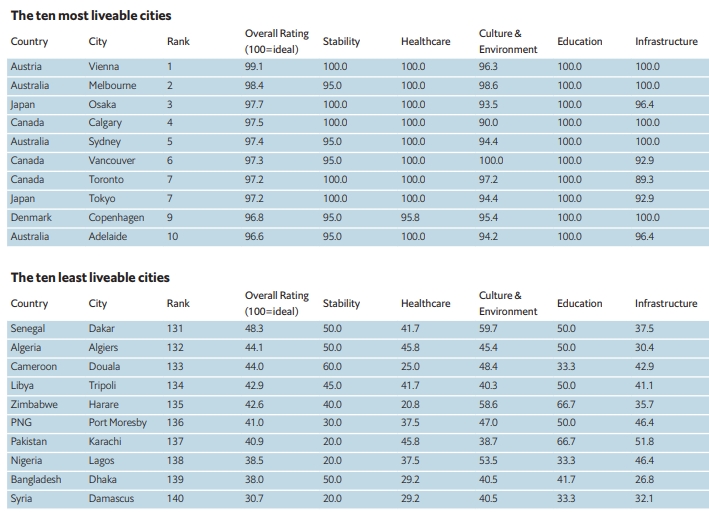

Global Liveability Index 2018 assesses which global cities provide the best or worst living conditions. This year, many cities have seen improvements in their ranking due to increasing stability across most regions. In this year’s Global Liveability Index 2018, Vienna displaces Melbourne as the most liveable city in the world.

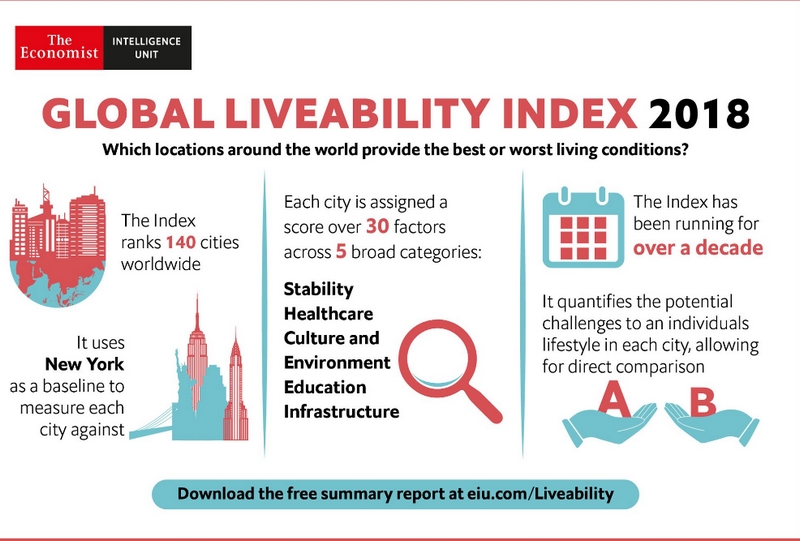

“The concept of liveability is simple,” says The Economist. “It assesses which locations around the world provide the best or the worst living conditions.”

“The new top spot in our is Vienna with a score of 99.1/100. The only thing stopping it getting a perfect score is the extremes in the weather.”

photo source: www.wien.info/en

The Economist Intelligence Unit‘s liveability rating quantifies the challenges that might be presented to an individual’s lifestyle in 140 cities worldwide. Each city is assigned a score for over 30 qualitative and quantitative factors across five broad categories of Stability, Healthcare, Culture and environment, Education and Infrastructure.

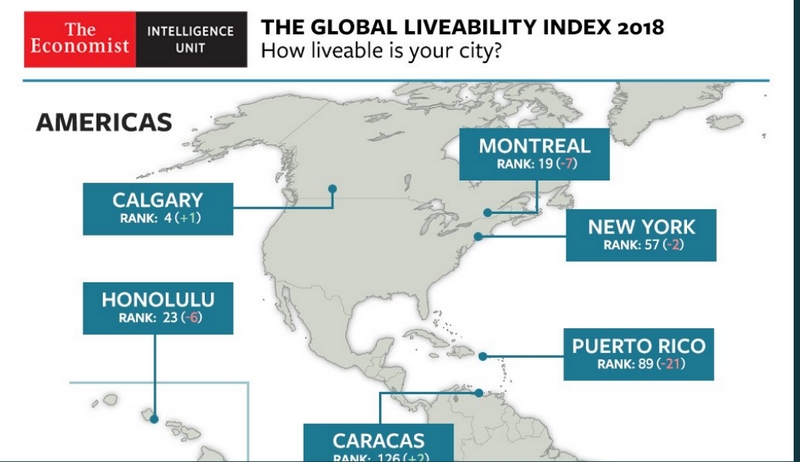

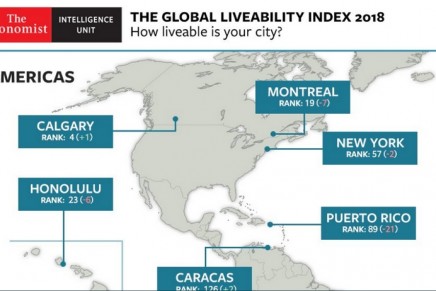

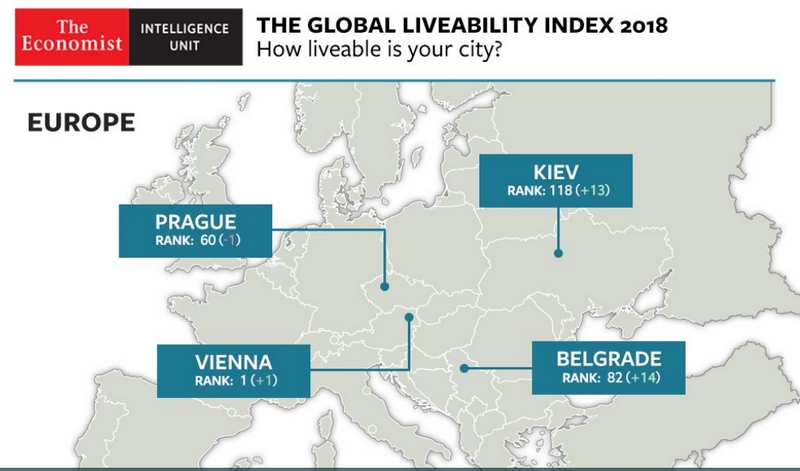

This year’s highest climber is Kiev. The capital of Ukraine is moving up the ranking 13 places. This reflects infrastructure improvements in the city, and greater stability and a declining crime rate in Ukraine. San Juan saw a sharp fall across several infrastructure indicators after two hurricanes hit Puerto Rico in 2017. This caused the highest fall for any city in the Index, down 21 places to 89th.

For the first time in this survey’s history, Austria’s capital, Vienna, ranks as the most liveable of the 140 cities surveyed by The Economist Intelligence Unit. A long-running contender to the title, Vienna has succeeded in displacing Melbourne from the top spot, ending a record seven consecutive years at the head of the survey for the Australian city. Although both Melbourne and Vienna have registered improvements in liveability over the last six months, increases in Vienna’s ratings, particularly in the stability category, have been enough for the city to overtake Melbourne. The two cities are now separated by 0.7 of a percentage point, with Vienna scoring a near-ideal 99.1 out of 100 and Melbourne scoring 98.4.

Global Liveability Index 2018; photos: twitter.com/baptist_simon

Global Liveability Index 2018; photos: twitter.com/baptist_simon

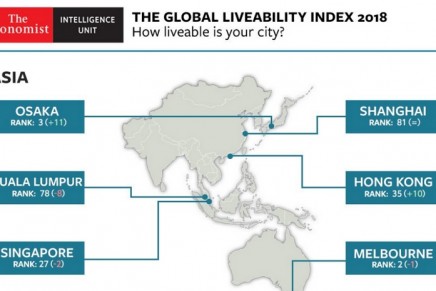

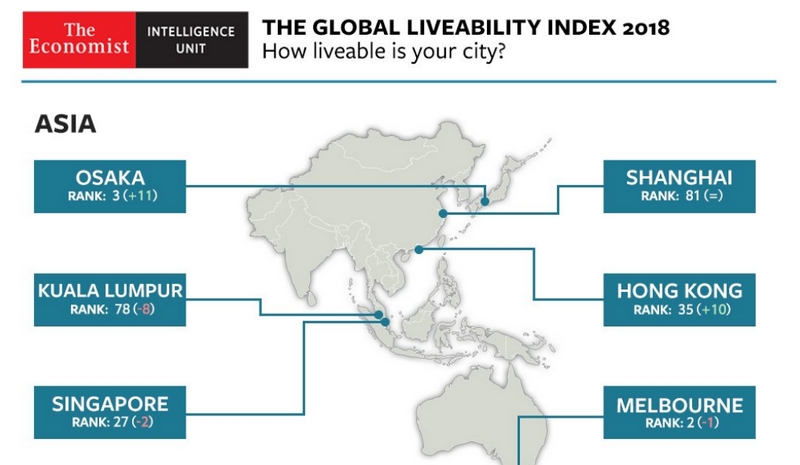

Two other Australian cities feature in the top-ranked places: Sydney (5th) and Adelaide (10th), while only one other European city made the top ten. This is Copenhagen in Denmark, in 9th place, after its score increased by 3.3 percentage points since the last survey cycle. The rest of the top-ranked cities are split between Japan (Osaka in 3rd place and Tokyo in joint 7th, alongside Toronto) and Canada (Calgary in 4th, and Vancouver and Toronto in 6th and 7th respectively). Osaka stands out especially, having climbed six positions, to third place, over the past six months, closing the gap with Melbourne. It is now separated from the former top-ranked city by a mere 0.7 of a percentage point. Osaka’s improvements in scores for quality and availability of public transportation, as well as a consistent decline in crime rates, have contributed to higher ratings in the infrastructure and stability categories respectively.

The only cities that have seen a fall in their stability indicators over the past six months are Abu Dhabi (71st) and Dubai (69th) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Colombo (130th) in Sri Lanka and Warsaw (65th) in Poland. In Abu Dhabi and Dubai, the threat of military conflict has increased owing to the UAE’s recent interventions extending its military reach in Yemen and Somalia. The UAE’s deployment of armed forces in Yemen, as well as political hostility with Iran, continue to pose a threat in the country and the region. Sri Lanka’s declaration of a temporary nationwide state of emergency in March, following clashes between Sinhalese Buddhist and Tamil Muslim communities, impacted Colombo’s civil unrest score. The threat of civil unrest also increased in Warsaw as an estimated 60,000 people joined a nationalist march on the occasion of Poland’s Independence Day in November 2017. Nevertheless, these changes have caused a decline in the overall stability rating only in Colombo’s case. Warsaw, for instance, has experienced a decline in the threat of terrorism to counteract the fall in the civil unrest score, while Abu Dhabi and Dubai saw improvements in their crime and civil unrest ratings.

Global Liveability Index 2018; photos: twitter.com/baptist_simon

The impact of improving stability is most apparent when a five-year view of the global average scores is taken. Overall, the global average liveability score has increased by 0.15%, to 75.7%, over the past five years, while the average stability rating has increased by 1.3%. Although the threat of terrorism has indeed caused a decline in liveability over a longer period—the global average livability score has decreased by 0.4% in the past decade—an improvement in scores over the past five years suggests a gradual return to relative stability.

Nonetheless, there does appear to be a correlation between the types of cities that sit at the very top of the ranking. Those that score best tend to be mid-sized cities in wealthier countries. Several cities in the top ten also have relatively low population density. These can foster a range of recreational activities without leading to high crime levels or overburdened infrastructure. Six of the top ten scoring cities are in Australia and Canada, which have, respectively, population densities of 3.2 and 4 people per square kilometre. These densities compare with a global (land) average of 58 and a US average of 35.6, according to the latest World Bank statistics, from 2017. Austria and Japan buck this trend, with respective densities of 106.7 and 347.8 people per square kilometre. However, Vienna’s city-proper population of 1.9m and Osaka’s population of 2.7m are relatively small compared with metropolises such as New York, London and Paris.

Global business centres tend to be victims of their own success. The “big city buzz” that they enjoy can overstretch infrastructure and cause higher crime rates. New York (57th), London (48th) and Paris (19th) are all prestigious hubs with a wealth of recreational activities, but all suffer from higher levels of crime, congestion and public transport problems than are deemed comfortable. The question is how much wages, the cost of living and personal taste for a location can offset liveability factors. Although many global centres fare less well in the ranking than mid-sized cities, for example, they still sit within the highest tier of liveability and should therefore be considered broadly comparable, especially when contrasted with the worst-scoring locations.