There was a time when Nineteen Eighty-Four required some suspension of disbelief: it didn’t seem possible, in the first several decades after the book’s publication, that any government or institution would have the resources and organisation to put transmitting and receiving devices in every home and then monitor the information they captured. We now know how very plausible that is. What Orwell didn’t guess was that people would, at the prompting of Amazon and Apple, actually invite such things into their homes. No state programme of installation was needed.

That the future has become the present, in shapes that weren’t quite predicted, is part of the premise of Hello, Robot, an exhibition now showing at the V&A Dundee. Its aim is less to stargaze the future than to question what is actually going on, now that smartphones, for example, have in effect made people into cyborgs – that is to say into interdependent alliances of the organic and the electronic. The show, to make its intention clear, is subtitled Design Between Human and Machine.

So the exhibition’s curators are particularly interested in such questions as the ability (or not) of machines to care and empathise. It features Paro, a white-furred baby cyber-seal that responds to sound and touch, makes cute seal noises when stroked and turns its dark, appealing eyes towards your face. A sort of pet, in other words, without a living animal’s drawbacks of defecation and death. It has been developed to comfort people with dementia and is used in more than 30 countries.

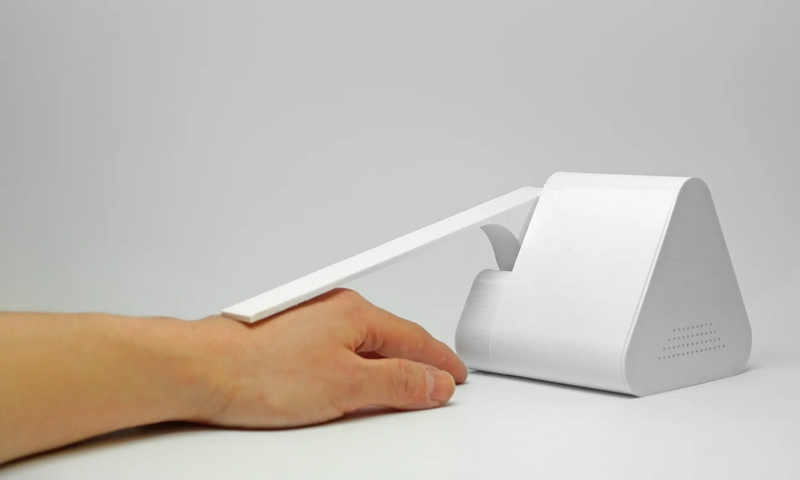

There is, as a sort of dystopian Paro, Dan Chen’s End of Life Care Machine, which strokes the hands of people near death and tells them that their families – who regrettably can’t actually be there – love them. Chen’s intention was not actually to put his invention into production, but to provoke reflection on Autonomous Vehicleswhether over-dependence on devices is leading humanity in this inhumane direction. He has been disconcerted when people have asked him where they can buy it. The Baby Feeder, an installation in which a robotic arm wields a bottle of milk, again questions the degree to which love and care can be outsourced to technology.

There are musings on the ethical implications of technology, such as Matthieu Cherubini’s video Ethical Autonomous Vehicles, in which self-driving cars have to decide – when confronted with an impending accident – which action to take. Depending on whether they are programmed to be “humanist”, or “profit-based”, or to be primarily interested in protecting their own passengers rather than passers-by, the cars will make different calculations about limiting the accident’s damage to property and human life.

The exhibition, first seen in the Vitra Design Museum in southern Germany in 2017 and making its only British appearance in Dundee, doesn’t want to wow people with the gee-whiz amazingness of new inventions; nor does it want to revert automatically to the nightmares that, going back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein by way of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, A Space Odyssey, are the customary flip sides of scientific optimism. The overall tone is cautiously positive. The aim is to make people think, which is why the exhibition mixes conceptual work like Chen’s with objects that really and truly are becoming part of everyday life.

With which ambition I have every sympathy, but it does make for a chewy experience, once you’ve got past a jolly first room of famous robots from popular culture – R2-D2, Arnie in The Terminator, Rosie the robot housekeeper in The Jetsons. There are a lot of captions to read and a lot of screens to scan. I find myself standing in front of an installation and video by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, designers who have long been reflecting interestingly on technology, but – despite having dutifully read some words on the subject – I still don’t really know what this exhibit is showing me.

At other times you’re left wanting to know more: about Leka, for example, a robotic toy that finds ways round the barriers to communication and interaction suffered by children with autism. On this there’s just a brief promotional video. On Bear (Battlefield Extraction-Assist Robot), which both rescues wounded soldiers and tries to reassure them with its friendly teddy face, there is just a single photo. The exhibition would benefit from fewer examples, gone into in more depth.

So assiduous is the show in asking questions that it leaves you wanting a few answers, or at least some propositions. All of which makes for a less gripping show than you might expect of this astonishing, world-changing technology. The protocols of museum display don’t help: Paro the robo-seal, for example, can only be seen in his transparent box, not handled and experienced.

Yet it remains an intelligent exhibition on an important subject, with some sights that will stay with you. I won’t forget Keiichi Matsuda’s Hyper-Reality, an animation of a possible future in which physical and virtual space have fused, such that a trip to the shops comes with disembodied faux-friendly faces hectoring and confusing you with special offers and loyalty programmes. I will also be haunted by a video of knife.hand.chop.bot, by the now disbanded artist collective 5Voltcore, whose users have to trust a robot to stab a knife into the spaces between their splayed fingers. The machine can be affected if they get nervous, and is more likely to make a mistake. Needless to say, given its health and safety implications, this is one of the show’s conceptual pieces. You won’t be able to get it on Amazon.

Hello, Robot is at V&A Dundee until 9 February 2020

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.