I have lived in Britain long enough to know that enthusiasm and cheerleading will never get you much credibility here – deprecation, misanthropy and a dash of inverse snobbery are the far cooler attitudes to adopt – so I apologise for the upcoming expression of total and unabashed positivity: there are so many brilliant films around at the moment. Go immerse yourselves in some Noel Gallagher interviews now to recover from that.

Whereas last year’s awards big hitters felt like a giant shrug of middle-of-the-road meh-ness – Argo, Silver Linings Playbook, Les Miserfreakingables – this year proffers films people might actually want to see more than once. Loath as I am to disagree with Joe Queenan, the best of the awards-lauded films this year – Dallas Buyers Club, Inside Llewyn Davis, Blue is the Warmest Colour, The Great Beauty, Twelve Years a Slave – don’t “feel like homework”, as he wrote last week (OK, Twelve Years feels a little like homework, but really mindblowing homework with emotionally tortured Fassbender, which is always the best kind of Fassbender). Rather, they are “enthralling, thrilling”, Queenan’s description of what a film should be, and there is no film more enthralling or thrilling than Her.

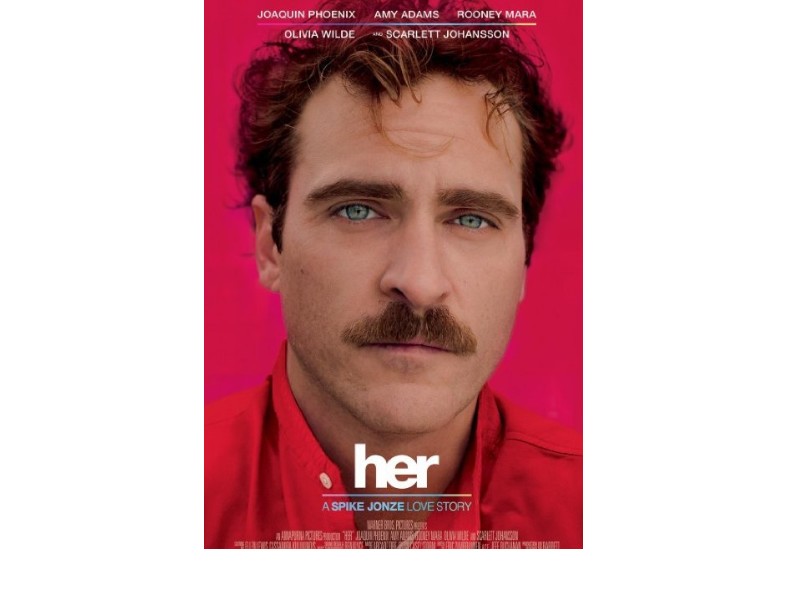

Written and directed by Spike Jonze, Her is a romantic, sad, funny, creepy and triumphant little film, and a definite retort to those who wondered if the depth of his two previous best films, Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, came more from the writer Charlie Kaufman than Jonze. I saw it two weeks ago while on a work trip to Los Angeles. Jetlagged and homesick, I was wary of this hipsterish-looking film with its Instagrammy filters and moustaches. I came out of the cinema, elated and dazed.

It’s a simple idea: a lonely man called Theodore Twombley (played fantastically by Joaquin Phoenix, who deserved a best actor Academy Award nomination far more than Leonardo DiCaprio for Wolf of Wall Street) falls in love with a seemingly autonomous computer programme called Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson). Simple, and yet audiences can read into it pretty much anything they want to, or need to: the lonely and heartbroken will see the movie as being about the death of love in the modern world. (Warning: do not see this film if you are heartbroken. You will probably throw yourself under a bus afterwards.)

Some critics have sneered that Theodore, who writes letters for a living, can’t actually construct a sentence, but that, surely is the point: there is no true emotion in this modern world, and it seems unlikely that Jonze would expect anyone to swoon at Theodore’s attempt at a love letter which includes the sentence, “The world is on my shitlist.” Feminists will see it as depicting modern men’s inability to relate to real women due to technology. (As well as Theodore falling for his phone, he relies on anonymous phone sex. There’s also a sideplot involving Theodore’s friend, Amy, played by Amy Adams, who lives with a man who constantly patronises and misunderstands her.)

We feminists can also see it as a cheering riposte to the assumption in movies that female sexiness has to involve flesh (Samantha doesn’t exist physically and Adams sports what has been described as “radically unsexy fashions”, and she is celebrated by the film. The only character in conventionally alluring clothes in the film, played by Olivia Wilde, is dismissed by Theodore as “not sexy.”)

Gossips have claimed that Her is Jonze’s response to Lost in Translation, directed by his ex-wife Sofia Coppola (although I’m as gossipy as any resident of Ramsay Street and I’m still struggling to see any real connections between the two films, maybe because Her is a very different – and much better – movie than Lost in Translation, being devoid of the latter’s racism and all). Aesthetes will love Jonze’s use of colour in the film, as pleasing and beautiful as Abdellatif Kechiche’s in Blue is the Warmest Colour. Even the Instagrammy filters made sense; a world that is bleached and sad.

Zeitgeist enthusiasts will delight in how weirdly plausible the films feels. When Jonze started writing Her, Siri hadn’t been invented; now expecting one’s smart phone to talk back to you is near commonplace. This week it was announced that Google has paid £400m for a British artificial intelligence firm that “aims to develop computers that think like humans”. Adario Strange writes on Mashable: “Her is the best and most widely accessible film we’ve seen about an idea known as the Singularity” (when artificial intelligence will overtake human intelligence). It can also be seen as a comment on the NSA debate, with Samantha gleefully rifling through Theodore’s emails. As Anthony Lane writes in the New Yorker, “Who would have guessed after a year of headlines about the NSA that our worries on that score would be best enshrined in a weird little romance by the man who made Being John Malkovich and Where the Wild Things Are?”

Internet addicts like me will see the film as a bang-on indictment of how so many of us use technology as a form of escape from our lives, while trying to convince ourselves it enhances it. In the film, everyone is bent over their phones, avoiding eye contact. And when I came out of the cinema, what did I immediately do? Bend over my phone and look for people online to talk to instead of talking to the actual people next to me with whom I’d gone to the cinema. But that was OK because they were doing the same: staring at their screens, white buds in their ears, blocking out the world. We all know this, of course, but sometimes you need to see a film about a man having sex with data for it to clarify.

Her won’t win best film or best director next month. At most, it might win best original screenplay. It deserves more, but it doesn’t matter. As a film, Her will live far longer in my mind than, say, American Hustle. As an enthralling, thrilling, romantic, beautiful, fun, weird piece of art, few things have felt more relevant.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.