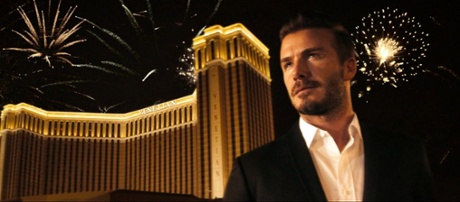

David Beckham leaves his private jet and travels in a limousine, from where he steps into the opulent Venetian casino in Macau, becoming the central attraction of a masquerade ball in full swing.

Revellers and dancers surround him as he smiles into the camera for the US casino group’s latest, lavish advertising push, launched this February just before Chinese new year.

With this advertising centrepiece, Beckham has become the public face of The Venetian, the flagship Macau resort of US billionaire – and US Republican party backer – Sheldon Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands Corporation.

Macau is built on a gambling industry so huge it has made Las Vegas look like a smalltown carnival, with its casinos turning over in excess of bn in the past year alone.

Macau is serious business – but it’s not all show business. The Macau casino scene has been repeatedly described by US authorities and independent experts as a nexus of money-laundering, triad operations, and an outlet for corrupt Chinese officials to spend the proceeds of their crimes.

But now the Chinese government is cracking down on the corrupt officials and money-laundering through Macau, and the stream of income from high rollers is rapidly drying up.

Such was Macau’s reliance on high-rolling, rather than retail – casual – gamblers that even at Chinese new year, a key date in the gambling calendar, Macau’s overall gaming revenues were down almost 50% on the year before.

If Macau’s casino and resort industry is to survive the crackdown, it has to change: the ultra-rich gamblers may not be there in such numbers as before, but the culture of luxury gambling trips, known as junkets, and fears of the ever-present triads in the background – remain. Macau needs to reform, fast.

Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands faces the same challenges as its US and locally owned rivals, but is perhaps the furthest ahead in facing those challenges. Its bid to reshape its Macau business focuses on bringing in more retail gamblers, revamping its casinos as bigger resorts with shopping malls – and the backing of brand Beckham provides the face of that drive.

This ongoing investigation by the Guardian and the Investigative Reporting Program of UC Berkeley reveals how the US casino groups made their billions against Macau’s seamy backdrop of triads, vice and corruption.

Next week, Adelson himself will give an account of his casino’s operations during Macau’s heyday, as he takes the stand for a hearing of a bitter legal dispute with a former employee, which has been shedding unprecedented light on the casino group’s inner workings.

The rise of Macau

What Hong Kong is to banking, Macau is to gambling. Like Hong Kong, the region was controlled by a colonial power – in Macau’s case Portugal, rather than the UK – until the late 1990s.

Gambling, already legal when Macau was in Portuguese hands, exploded after China re-established control. The operating of casinos in Macau was long a monopoly for just one man, the billionaire Stanley Ho, but in 2002 authorities opened up concessions to Chinese tycoons and a small number of foreign bidders – who jumped at the prospect.

The foreign winners mostly came from America. The first to build was Adelson, in 2004. It made him a multi-billionaire who would become notorious for his strident views on US and Israeli politics.

Adelson’s personal income from his casino and resort operations has grown exponentially, reaching m a day in 2013 and today giving him a personal net worth in excess of bn. Adelson channels tens of millions of dollars into Republican causes – with donations well in excess of m to candidates and PACs – conduits for political funding – in the last presidential election cycle, he is among the party’s primary funders.

It’s Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands casino group to which Beckham is affiliated, having signed a deal in November 2013 for a dining concept “partnership” between Beckham Ventures – the commercial vehicle the Beckhams co-own with Simon Fuller – and Las Vegas Sands for its resorts in Macau and Singapore.

A representative for Beckham said the former footballer worked with Sands Group across Asia, and had no operational role with its gaming side beyond the promotion for The Venetian resort.

“David is working on a dining concept with the Sands Group across Asia, just as some of the greatest and most respected chefs and retailers in the world have done,” he said. “He is also supporting a number of local charitable initiatives. We are not involved on the gaming side.”

Las Vegas Sands is publicly listed in the US, and like all casino groups in the country is required to operate casinos within the strict bounds of state and federal regulators.

But while Macau started out providing just a fraction of the revenues for Las Vegas Sands and those who followed it, the Chinese region has come from almost nowhere to dramatically outstrip Vegas.

In 2004, Macau’s gaming revenues of around bn lagged behind the bn generated in Vegas – and American groups received almost none of it. By 2012, Las Vegas Sands generated more than 50% of its revenue from Macau alone, while a single special dividend at the end of the year generated .2bn in cash for Adelson. The billions Adelson generates from his Macau resorts render his huge contributions to US politics as virtual spare change.

By last year, Macau’s gambling industry generated close to seven times more than the Las Vegas Strip, and US companies, including Las Vegas Sands, Wynn Resorts and MGM, took more than a third of it: Vegas may be their spiritual home, but for moguls such as Adelson, Macau is where the biggest money is.

But only if you can get the right people in the doors.

The seamy side

Macau, though, isn’t like Vegas. The bulk of the casino revenue in the province doesn’t come from people shoving a few dollars of their savings into slot machines or roulette: the real action – and substantial share of the casinos’ profits – has come from high rollers, betting up to hundreds of thousands of dollars a game in VIP backrooms.

These VIP rooms work quite differently from regular casino operations. Groups of promoters attract and corral high net-worth individuals from across the east Asian region for gambling junkets, often chartering private jets and laying on special accommodation for the sessions.

The casinos hand over a significant degree of control of their VIP rooms to the junket operators, in some cases going as far as simply getting a share of the takings in exchange for providing the facilities.

The US companies stress they maintain safeguards and control over what happens on their premises.

Organising Macau’s high-rolling junkets is no simple affair. One problem is that it is not legal for wealthy Chinese business people and officials to take much money out of China at one time. The limit is about ,300 a visit, and no more than ,000 a year.

One solution is for the junket operators to extend credit to their wealthy guests. Any losses can be paid after the trip, back in China.

The only wrinkle is that as gambling is not legal in China, such debts cannot be enforced in the courts. Other measures have to be taken to ensure that a gambler will always pay off debts.

These debts are not owed to the casinos, but rather to the junket operators and their financial backers, who settle up with the casino at the time and take the risk of the debt themselves.

This results in a web of licensed junketeers, guarantors and investors that industry experts say makes it difficult, if not impossible, to know exactly who is involved in any given junket – though casino groups insist their due diligence procedures mean they know who they are dealing with.

Debt collection is an issue, even those involved in the junket business will acknowledge. Tony Tong, a financier who backs Macau junkets, acknowledged “collection of gambling debt is illegal in China”.

Tong said that junkets and their backers recouped debts through traditional channels, even if they were not legally enforceable, but in some circumstances could use less conventional measures.

Tong said it was on debt collection where triads traditionally became involved. He explained that debts could be collected by “following the guy until he pays … or many people follow them. If the guy has 10 guys, you need to have 50 guys following them. So that’s just part of that business.”

“If you can’t enforce it in the legal system, what can you do?” he concluded.

People who have worked in law enforcement in the region are more explicit: in some cases, they say, triads enforce gambling debts through violence.

“You don’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to work out that obviously triads and organised crime figures are closely connected to junkets because of the necessity to enforce on losses,” said Steve Vickers, a former Royal Hong Kong police commander who specialises in Macau’s gaming sector. “The triad society members can be very brutal in pursuing debts, everything from simply knocking on your door and ringing you up five times a day … to physical assault and whatever.”

Triads play a strange role in Chinese society, according to Vickers: membership is illegal, so wouldn’t generally be admitted – but nor would people generally be prosecuted just for being a member.

“Triad membership is a criminal offence, so they won’t tell you that they’re triad … generally the government don’t prosecute people solely for triad membership,” Vickers added.

“Once you’re a triad [though], you’re a triad. I’m sure you can become less active. But like other global criminal organisations, once you’re in, you’re in.”

While triads are not given leave to operate inside US-owned casinos – as even the independent experts stress – they are endemic throughout Macau’s independent network of junket operators, which brings in the high rollers, and with them a huge swaths of casino revenue.

The result of this opaque network is tens of billions of dollars of untraceable money cycling in and out of Macau. A 2013 report from an advisory committee to the US Congress cautioned “the real value of Macau’s gaming industry is likely six times larger than the official reporting size” – making the actual revenues something in excess of 0bn.

The same report starkly warns this is a huge money laundering risk.

“It is the variety, frequency and volume of transactions that make the casino sector particularly vulnerable to money laundering,” it states.

“In Macau there is an even bigger risk of money laundering within the VIP gaming room operations, which are physically conducted within the casinos, but remain outside of the casino’s official oversight.”

If Macau resembles Las Vegas, it’s not the cleaned-up Vegas of 2015, but something a bit more like the Vegas of the 1950s – but on a far larger scale.

Prostitution is legal, and the culture is at least tolerant of the triads – with violence on rare occasions spilling into the streets. International authorities look on with mounting interest as untraceable billions flood in and out of the city.

The problem for the big US casino groups such as Las Vegas Sands, which are heavily regulated in the US, is how they deal with this backdrop. The casinos point to steps they have taken, including working to take stronger controls over VIP junkets in their premises, including electronic monitoring and auditing.

Further, as US companies are subject to US laws such as anti-money laundering protocols and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, there are regular reviews and audits by US authorities of casino groups’ policies to detect and avoid associating with known criminals. Such reviews routinely acknowledge the risks of Macau as an operating environment, but have consistently recertified the major casino groups’ procedures.

The casino groups say their internal procedures have resulted in some of the most rigorous, strictly enforced and effective anti-crime policies anywhere in the world.

‘The top guys, the biggest’

One of the key figures at the heart of Macau’s casino and junket industry is 66-year-old Charles Heung, an actor-turned-producer-turned-film mogul and financier.

Heung is the very model of the new Chinese elite, with impeccable connections. Tao Siju, a former business partner of Heung, served as China’s minister of public security in the 1990s, while Heung’s politically connected wife, Tiffany Chen, was at the forefront of those denouncing Hong Kong’s recent student protests.

Heung is unafraid to lavish attention on his wife: in 2013 he bought her the world’s most expensive briolette-cut diamond, a 75.36-carat stone worth HKm (£7.3m)

Heung’s family were once not so respectable. In 1919, Heung’s father founded the Sun Yee On, to this day one of the most influential triads in Hong Kong, China, and beyond. Two of Charles Heung’s older brothers, Chin-Sing and Wah-Yim, were convicted and jailed in 1988 as its leaders, though later cleared on technical grounds at appeal.

Heung has resolutely and consistently denied ever being involved with Sun Yee On. In a rare 1997 interview with the New Republic magazine he acknowledged that his family had a “a mafia background”, but denied personal involvement or knowledge, saying he had worked harder as a film producer to overcome his family name.

Still, for decades Heung has been haunted by his family past. In 1992 a US Senate report on Asian organised crime – which has been contested for not citing its sources – listed Heung as a senior figure on a Sun Yee On organisation chart, explaining the group was “linked to a wide variety of criminal activities, including heroin trafficking and control of the entertainment industry in Hong Kong”. The report did not mention Heung in its body text, nor explain why he appeared on its chart.

Two years later, a New York racketeering trial heard claims from Kwong Wing Wong, who said he had been an enforcer for Sun Yee On in Hong Kong – “I wounded people who are using knife, and gambling house” – and described Charles Heung and four of his brothers as “the top guys, the biggest” in the triad.

Sun Yee On’s criminal activities have continued. Last year the South China Morning Post tied the triad to the trading of raw materials for methamphetamine with Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel, as well as with infiltrating the protest camps of Hong Kong’s student protest movements, reporting that police were investigating triad links to attacks on the students.

Charles Heung has never been arrested, charged or prosecuted for any alleged ties to the Sun Yee On triad – but they continue to haunt him. As recently as early 2015, he and his wife both appear in the US Homeland Security computers as having been denied visas by the State Department, and therefore entry into the United States, according to a senior Department of Homeland Security official.

Heung’s entry on the register states he has an “affiliation with Asian organised crime”, while Tiffany Chen’s records her as “the spouse of an Asian organised crime figure”.

Heung and the high-rollers

Documents suggest Heung was a significant figure in Macau’s VIP junkets, including those at Las Vegas Sands’ casinos.

This is set out in a 2010 report prepared for Steve Jacobs, then the CEO of Sands’ Macau operation, and a key Adelson aide, who is suing the group for wrongful termination. The short report, which focuses exclusively on Heung, combines a variety of public domain sources, such as the US Senate report, as well as private intelligence databases to detail Heung’s alleged triad ties, before noting Heung was the “guarantor”, or financial backer, of at least two junkets operating within Las Vegas Sands’ Macau casinos.

The covering note of the memo, from Venetian Macau’s then executive director of surveillance, describes the results of a “simple surface search”.

“Apart from being one of the most successful film producers in Hong Kong, Heung is also one of the most controversial due to his family’s triad background,” it says. “Heung is widely suspected of ties to one of Hong Kong’s largest and most powerful organised crime groups, the Sun Yee On triad.” The note ends with a promise: “I will get more detail.”

No room at the casino

By November of 2013 – just as brand Beckham was hitching up with Las Vegas Sands – Charles Heung abruptly found himself unwelcome in Adelson’s casinos.

Heung was gambling – or trying to – with a group of high rollers around the time of Chinese new year. On trying to enter Las Vegas Sands’ Macau casinos, Heung and his group found themselves turned away. Not deterred, the group travelled by private jet to Adelson’s flagship Singapore casino – where Heung was rejected again.

The incident was emblematic of a series of heightened actions Las Vegas Sands appears to have taken to keep those it regards as undesirable figures out of its operations. Its measures have included hiring former FBI officers to beef up internal security, and new audits of customers and junket operators.

Statements from Las Vegas Sands now say the company has “no business relationship or otherwise” with Heung.

More broadly, the company’s vice-president of communications, Ron Reese, said Las Vegas Sands had invested in “Macau’s future as a centre of leisure and business tourism” and had tight controls on its gambling operations.

“Las Vegas Sands takes its regulatory obligations with the utmost importance. In fact, we strongly believe we are the industry leader in this area and specifically our anti-money laundering programme,” he said.

“Additionally, our company has been frequently cited as leading the industry in its commitment to regulatory compliance.”

Another US casino mogul, Steve Wynn, the billionaire owner of Wynn Resorts – which owns and operates casinos in Macau – and another major Republican backer, has suggested that “triad” should not be seen as a synonym of mafia, or even organised crime.

Speaking at a Massachusetts Gaming Commission hearing in October 2013, Wynn rejected suggestions that Macau could bring disrepute on the state, should Wynn Resorts be granted a licence. “What in Macau could threaten or bring disrepute on Massachusetts?” Wynn was asked at the hearing.

“A piece of unsubstantiated raw intelligence about a junket operator reputed to be, for example, a member of a triad,” he replied.

“That immediately presupposes the triad is synonymous with mafia, which is completely false. Experienced law enforcement people will tell you that triad is not a synonym for organised crime.”

The Massachusetts board approved Wynn Resorts to build and operate a casino in the state, but the recommendation is now subject to a legal challenge from the city of Boston.

Several experts in the law enforcement community regard an individual being involved with triads as a serious sign of bad character. “Wow. As someone who’s spent 17 years fighting organised crime, that’s certainly news to me that not all triads are bad or associated with crime,” said Jennifer Shasky Calvery, director of the financial crimes enforcement network (FinCen, a bureau of the US Treasury), said when she heard a version of Wynn’s quote.

Others report being contacted by at least one US casino group keen to get former police officers to say positive things about triads or those with ties to them.

Martin Purbrick, a former intelligence officer for the Royal Hong Kong police, said he had been contacted by a “major US casino operator” who asked him to “state publicly that Mr Charles Heung Wah-Keung is a reputable businessman”.

“Heung Wah-Keung was in fact named in a US Senate report as an office bearer [ie senior member] of the Sun Yee On triad society,” he continued. “I declined the request on the basis that the assertion by the casino operator is widely held by former Royal Hong Kong police officers to be untrue.”

Wynn Resorts has yet to comment on whether Charles Heung – or the junkets he backs – are welcome in its Macau casinos, and Wynn has never personally commented on Heung. A lawyer for Wynn Macau told the Guardian any allegations against Heung were “innuendo”, but declined to comment on whether the group had ever had any relationship with the celebrity junketeer.

The lawyer said: “It is not our practice to identify our customers or participants in junkets we do business with. However, we obtain criminal clearance certificates from the home police department (such as Hong Kong police department) for anyone that has a financial relationship with a junket doing business with us, and we disqualify anyone who does not comply with our strict procedures or who does not receive a clean criminal clearance certificate.”

A change is gonna come?

For a decade, Macau’s gambling industry has engaged in a wary but vastly lucrative relationship with junkets of China’s richest pleasure-seekers, and the triads who help those junketeers – with revenues and profits increasing markedly for much of the past decade.

But it appears good times may be coming to an end. China’s new president, Xi Jinping, unlike some of this predecessors, has paid more than lip service to crackdowns on corruption, taking a harder line on party figures who spend too lavishly – including on trips to the province.

This crackdown has been accompanied by a drop of 2.5% in Macau’s gaming industry revenue in 2014 – the first year-on-year decline for several decades and a sign that the heady growth may be a thing of the past.

The early figures for 2015 are dramatically worse: January revenues were down 30% year-on-year, while in February – the crucial month containing Chinese new year, and the month the Beckham advertising push was launched – were still worse, down almost 50% on the previous year. Compared with its rivals, Sands was relatively sheltered from the storm, thanks to broadening its business into the leisure and conference sectors.

That may not stop those – reputable or otherwise – who have grown rich and powerful through the trade.

Within Macau, the fightback relies on reshaping the industry as a resort with more than gambling going on – much like modern Vegas. On one side, there’s the marketing muscle and internal reforms of the US casino groups, with the PR side of the operation leaning heavily on brand Beckham. On the other lies the remaining junket operators and the triad groups who have grown rich through Macau’s web of vice, connections and black-market money.

And for Adelson himself, a particular headache looms. Mystery surrounds the operation at the top of his companies: Adelson is known not to use email, and communicates with his executives verbally. But he is set to take the stand next week in a public hearing for a wrongful termination suit from his former Macau chief executive, Steve Jacobs.

The bitter suit, which has run for a period of years, has seen Adelson retaliate with a defamation suit of his own – now dismissed, though a counter-suit on defamation filed by Jacobs is ongoing – while the company’s representatives have suggested Jacobs stole documents and was trotting out “tired and false accusations” against the company and Adelson, all of which Jacobs denies.

Macau’s golden era of gambling may be reaching its end – but only now might we all get a chance to see what the view from the top was like while the party was in full swing.

- Guardian US will be reporting from Las Vegas when Sheldon Adelson takes the stand at the hearing, on 28 April

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.