The love-in between Instagram and fashion could be summed up by the most liked picture of the last five years: the selfie of model Kendall Jenner lying on the floor in a lace dress with her hair arranged into hearts. It gained 3.1m likes and, with the hashtag “hearthair”, more than 10,000 followers shared their versions of the picture. This is the extreme end of online influence but it does demonstrate what fashion has known for a while. In a world where nothing happens unless it’s on Instagram, the # is everything – and retailers are using it for commercial gain.

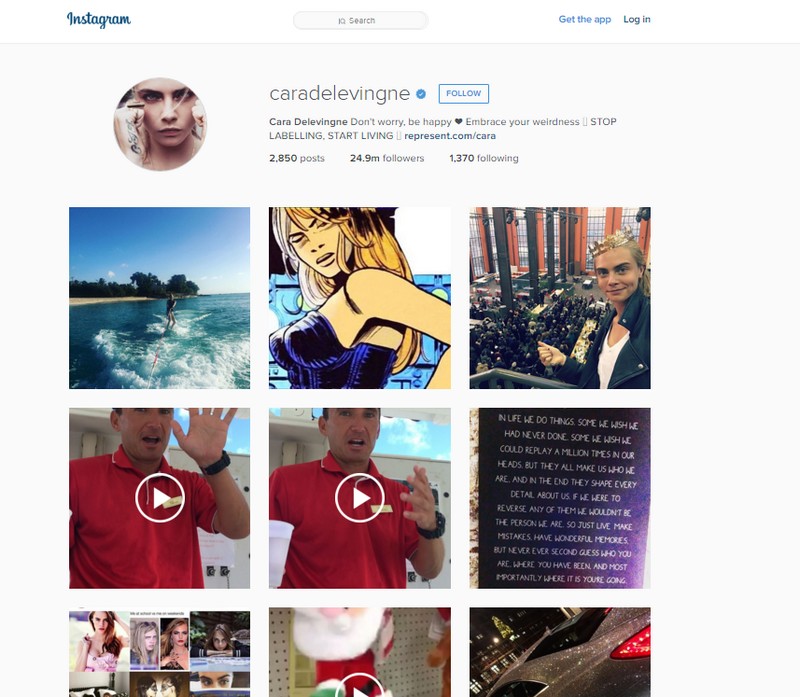

What is trending on the social media platform has the potential to have more of an effect on what fashion will look like going forward than anything on the catwalk. So-called Insta-models – the likes of Cara Delevingne, Gigi Hadid and Kendall Jenner, with million-plus followers – are often paid for their frequently shared content, and can charge companies up to $300,000 (£200,000) per post. Brands are also collaborating with them in order to garner some of this influence. Topshop featured Hadid in its campaign in a bid to tap into her 10 million followers and the images gained nearly 700,000 likes. They then collaborated with Kylie and Kendall Jenner on a range of clothing – with the siblings’ nearly 90 million combined followers surely a major factor in the deal.

Instagram’s influence is now directly feeding into what high-fashion stores are buying – especially as the demand for smaller, niche labels grows. Lydia King, buying manager at Selfridges, calls the app a “great tool to find new labels from around the world and to instantly see how potential consumers are reacting to and interacting with these niche brands”. It was instrumental in the store’s stocking of their new Everybody section, which specialises in fitness brands. “More than ever, buying this category is about a particular lifestyle,” says King. “Being able to see people’s travels unfold on Instagram is inspiring, and has given us an entirely new way to select brands for Selfridges.” Labels Kiini (crocheted swimwear) and the Muzunga Sisters (pom pom’d beach cover-ups) were both sourced in this way – and hit that sweet spot of an instantly identifiable aesthetic that looks great in a selfie.

Sarah Rutson, vice president of global buying at Net-a-porter, uses Instagram as a resource for her team to “find a particular product or type of brand that we think fills a gap in our offering”. This was the way the site found Martiniano. A small Argentinian brand that first made the glove shoe, since popularised by the distinctly un-web-friendly Céline (which doesn’t sell online), this was a way of circumventing Céline’s e-commerce black out and allowing her customers to get the look. “It was a ‘bingo’ moment,” says Rutson.

Instagram helped her think laterally about fulfilling demand that already exists, such as for the Ukrainian Vyshyvanka embroidery used by their popular brand Vita Kin – originally found through the Instagram of fashion blogger Man Repeller. “We saw how much our customer loved the product, but the stock was simply not available,” says Rutson, who searched through more than 10,000 posts relating to Vyshyvanka. “I found [other Ukranian brand] March 11 when I was killing time waiting for my luggage at an airport.”

Ultimately, Instagram as an interface between consumer and retail is a concept still in its infancy – but it will grow with a new demographic of consumers who have lived their lives through the prism of posts. “My generation have embraced social media in a big way,” says Rutson “but I think we will only really see the full influence that Instagram carries once the younger generation who have grown up with it all of their lives start to have spending power.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.