Issey Miyake is quite excited about his paper suit. “It doesn’t crease!” he tells me as he smiles and scrunches up a bit of his sleeve with his fingers. It springs back to perfectly smooth.

The suit itself looks very straightforward: a smart blue single-breasted jacket with matching trousers, no low crotch on the trousers, no asymmetry; the sleeves are both where you expect sleeves to be; there’s not even a random pleat. But this is typical Issey Miyake. In more than 45 years of designing clothes, he has never stopped innovating. He has an obsession with making clothes that are light, practical and washable, and that don’t crease.

Miyake, 77, doesn’t do much press these days. He has a youthful face, wavy hair which is turning grey, and he walks with a pronounced limp – a result of surviving the atomic bomb dropped on his hometown of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, when he was just seven. His mother died of radiation exposure within three years of the bomb. It’s not something Miyake talks about, but in 2009 he wrote about it in the New York Times to support an invitation for Obama to visit Hiroshima for the anniversary of the first atomic bomb. “In April, President Obama pledged to seek peace and security in a world without nuclear weapons,” he wrote. “He called for not simply a reduction, but elimination. His words awakened something buried deeply within me, something about which I have until now been reluctant to discuss.”

In December he spoke again about the day the bomb dropped, telling the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun how he heard the boom as he went into a classroom after morning assembly. After he found his mother at home, she told him to leave for the countryside. No wonder Miyake doesn’t like looking back.

Last month he made a rare public appearance. A major exhibition of his work from almost half a century, Miyake Issey Exhibition: The Work of Issey Miyake, was opening at the National Art Centre Tokyo. At the press conference Miyake didn’t dwell on his past achievements but instead talked about what he was planning to work on next. He opened up a suitcase. In it was a big piece of handmade washi paper, and a simple kimono-type jacket made crudely out of the paper. “I am very interested in the culture of paper,” he said.

He has been researching the material and had been sent this particular paper, which was woven by hand by a craftswoman in Shiraishi in the Miyagi prefecture in the north of Japan. “She sent it to me to archive,” he tells me when we spoke after the press conference. He was keen to chat despite the fact that there was a crowd gathering in the entrance to the museum to hear him officially open the exhibition. One of his brightly coloured flying saucer dresses hovered above them as they waited, suspended from the ceiling.

“Indian paper is famous, Egyptian papyrus, Chinese paper … every country has used this natural material. But the problem is it’s going to run out because it’s very difficult work,” he tells me in his fluent English. “The woman who made it and sent me the package is 96 now. There is nobody to inherit this precious technique. Depending on how you produce it, it could be useful for many things.” There used to be 300 paper making workshops in Shiraishi, which was badly damaged by the 2011 earthquake. Now there is just one.

Tradition is very important to Miyake. It is the fusion of the most basic of materials and ancient of traditions with new and innovative techniques that has kept his brand at the forefront of fashion – technically if not always critically – for the past four and a half decades. One of his biggest fans was the late Zaha Hadid, who loved wearing his clothes.

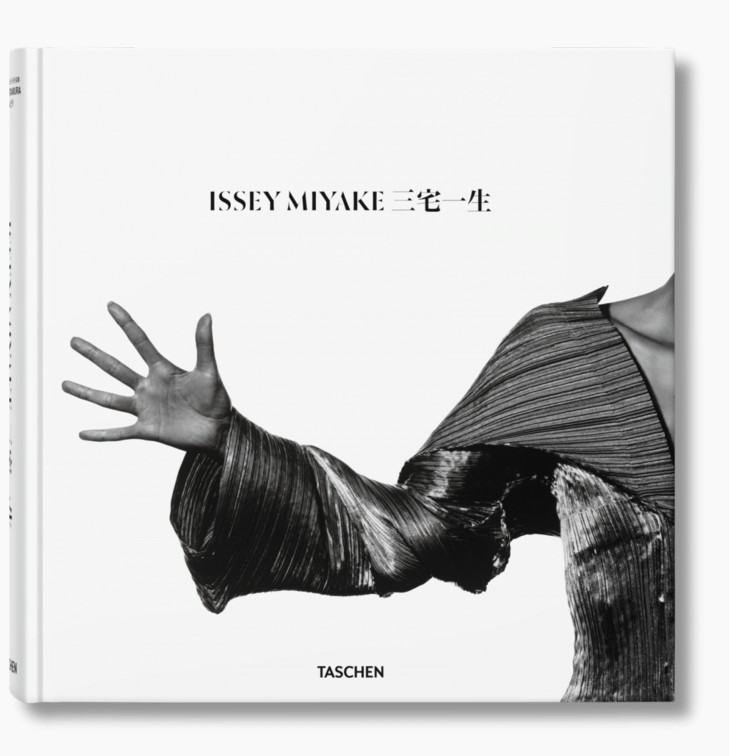

When Taschen publishes its definitive survey of the designer’s work this month (a Sumo-sized tome simply called Issey Miyake) we can expect to see the ripples of influence for years to come.

Designer of the moment Jonathan Anderson recently told Business of Fashion: “I’ve always been obsessed by him and how he worked with so many different types of people.” The London-based French designer and 2015 LVMH prize finalist Faustine Steinmetz is similarly fascinated, particularly with how Miyake has developed a universal clothing product with Pleats Please – one of the only labels she wears apart from her own.

These are clothes that are made from polyester and can be machine washed, rolled up in a suitcase and unpacked to look as crisp and springy as they did when you packed them; they are light, ageless, trans-seasonal, cross-cultural, ambisexual (there’s a men’s range, Homme Plissé, because Miyake realised that 10% of Pleats Please customers were men), and don’t cost a fortune.

At the exhibition, I was struck by how timeless – and relevant – the clothes are, even the early pieces like Sashiko (AW71) which is made from hard-wearing quilted fabric used for Judo uniforms and farmers’ work clothes; Tanzen (SS76/77), a loosely cut kimono style coat with a tie belt; and Shohana-momen (SS76/77), a red shirt and cropped trouser set made from fabric traditionally used to line men’s kimonos. Each garment is exquisitely displayed on a figure. The “grid” bodies are made from 365 pieces laser cut from a single sheet of corrugated cardboard and acrylic plastic and then ingeniously slotted together to form the shape of a human body.

Miyake anticipated sustainability issues in the industry long before they were a talking point. I ask him what he thinks the key challenges will be for future generations of fashion designers. “We may have to go through a thinning process,” he says, meaning that we may have to consume less. “This is important. In Paris we call the people who make clothing couturiers – they develop new clothing items – but actually the work of designing is to make something that works in real life.”

In other words, clothes shouldn’t be a frivolous end in themselves, but should have a purpose – they should offer a solution. “The important thing is to make something,” he says. “In reality it’s not important that a designer be known by name –you can remain anonymous. Even the status of a designer will undergo changes, I believe.”

Next month Miyake’s designs will be featured in an exhibition at the Costume Institute in New York, Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology. The museum’s curator, Andrew Bolton, was in Tokyo for the opening of Miyake’s exhibition. The pieces he will be exhibiting in New York include his SS94 flying-saucer dress and the 1999 A-POC. “Miyake’s clothes have an aura about them,” Bolton says. The A-POC in particular is the perfect fusion of computer technology and basic knitting machine. With his textile engineer at the time, Dai Fujiwara, Miyake worked out a way to create clothing that is knitted from a single strand of thread without the need for additional sewing or cutting. It is an industrialised process that eliminates the final cutting and sewing.

According to Lidewij Edelkoort, the fashion predictions guru who runs the company Trend Union, Miyake is the past, present and future of fashion. “How creative can one person be?” she asks. “It is exceptional for a living person to have this body of work. There is a consistency in taste, colour, shape, yet evolving innovation, and always this keen interest in textiles.”

As a child, Miyake wanted to be an athlete. One of the exhibits in the show is the official uniform he designed for the newly independent Lithuanian team for the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. Linked with his love of sport, Miyake’s clothes have always allowed freedom of movement, and his shows highlight their flexibility (and often bounce-ability).

He studied in the graphic design department in Tokyo’s Tama University in the 60s and left Japan for Paris in 1965. He enrolled at the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne to learn how to make clothes and went on to work with Hubert de Givenchy. It’s odd now to think of him sketching dresses that Audrey Hepburn might have worn – many worlds away from the uncompromisingly futuristic, industrial clothing he went on to create. Hard to imagine how his early couture training would result in him collaborating with, say, his friend the product designer Ron Arad in making a chair covering that could double as a piece of clothing (another A-POC innovation).

But Miyake witnessed the 1968 student protests and was not interested in dressing bourgeois ladies who lunched. After Givenchy he worked with Guy Laroche and then Geoffrey Beene in New York. He established the Miyake Design Studio in 1970 and showed his first collection in New York in 1971. One of his earliest pieces is a jersey body from 1970, hand-painted using traditional Japanese tattoo techniques with a portrait of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. The print was created by one of Miyake’s longest-term collaborators, Makiko Minagawa (she now has her own label, HaaT, produced by Issey Miyake Inc).

This has always been a collaborative effort. Recently the Miyake Design Studio worked with the archive of the late Japanese graphic designer and Muji co-founder Ikko Tanaka, using an image from his 1981 poster of Nihon Buyo dance for a collection of Pleats Please clothes and accessories.

But perhaps his most famous collaboration was with American photographer Irving Penn. For 14 years from 1986, Miyake’s attaché de presse Midori Kitamura was dispatched to New York to spend four days each season to work with Penn. She would spend a day showing Penn the clothes she had brought from Tokyo – trunks of them – and then he would get a model to try them on and strike abstract poses which would require Kitamura to pile on more clothes, and create volumes where there weren’t any by wrapping another layer or tying a dress around the model’s head.

“Penn shot for Vogue, where the clothing should be shown in a very formal way, but in our case he was completely free,” recalls Kitamura, who was putting finishing touches to the exhibition when I meet her. “Each time it was a challenge to do something Issey would find stimulating.”

Kitamura has been Miyake’s right-hand woman (she is now president of the company) since the mid-70s. It was her job to select pieces for the exhibition from thousands in their archive. She says that Miyake kept everything from the beginning, anticipating, perhaps, their importance.

A tall woman dressed in a combination of Issey Miyake pleats and Roger Vivier pumps, she started working with Miyake as a fitting model when she was 21. He liked that she gave him honest opinions about his clothes, occasionally saying she didn’t like something. She would travel to Paris with him to help select models and style the shows. “Designers would invite us for dinner at their homes. There was a real community in those days,” she says. They would socialise with Sonia Rykiel, Emanuel Ungaro, Jean-Charles de Castelbajac and Kenzo.

In 1994 Miyake handed over the reins to his main fashion line for men – followed by womenswear in 1999 – to his former assistant Naoki Takizawa so that he could concentrate on his research projects, including the opening of 21 21 Design Sight in 2007. He continues to oversee all the collections. (Takizawa is creative director at Uniqlo, so Miyake’s influence can be felt right down the clothing food chain). Yoshiyuki Miyamae took over womenswear in 2011.

Whether it is with paper or digital production techniques, Miyake’s team continues to innovate, most recently with the Bao Bao, a Blade Runner-style bag made from a flexible grid of vinyl triangles linked together with a polyester mesh. It is a bag that has truly gone viral. You see it everywhere, from the streets of Tokyo to the farmers’ markets of London.

But the secret of Miyake’s success (his business is still privately owned, with 133 stores in Japan and 91 internationally, plus eight lines of clothing and bags, as well as fragrances, lights and watches) is not that he has embraced technology, more that he has managed to use it in a way that fuses the innovative – the industrial and the digital – with the most elemental of crafts. In 2007 he launched his Reality Lab. “It’s quite amazing to see Japanese technology,” he says. “We develop many different things, but happily I have a great team of designers. I am going to let them get on with it, and this way I can be free to explore.”

He’s always been a free spirit with his own way of working – at his own pace. “It’s different from the collections that happen every six months. Tradition takes time, but that’s something I am very interested in now.”

At the exhibition opening Miyake was presented with the cross of the Commander of the Légion d’honneur (an award he shares with Karl Lagerfeld who was given it in 2010). He didn’t come out to the celebration dinner, preferring a quiet night in. But I heard he wore his medal for the rest of the night, no doubt dreaming of his next challenge, how to make the world a better place using that most fundamental of materials, paper.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.