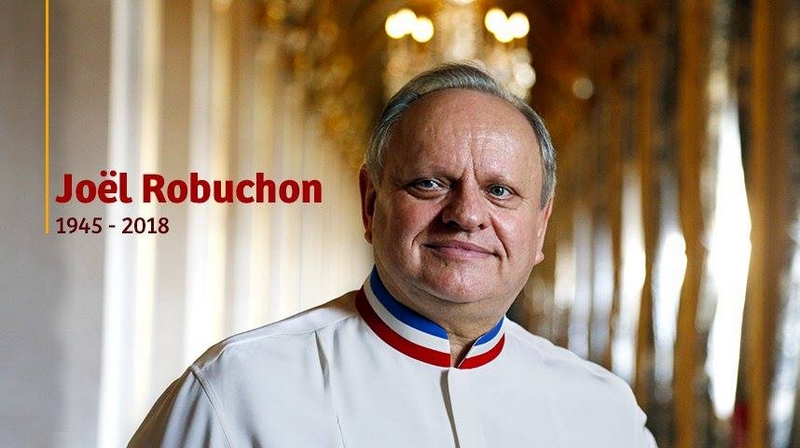

Joël Robuchon, who has died of cancer aged 73, was the last of his kind – a French chef who was universally acknowledged as the greatest in the world at a time when French haute cuisine was still the standard by which all other food was judged.

His open-minded and informal approach to the business of fine dining opened the way for the vivid creativity of Ferran Adrià, Heston Blumenthal’s playful and exquisite dishes and the Nordic culinary jazz of René Redzepi. “To describe Joël Robuchon as a cook is a bit like calling Pablo Picasso a painter, Luciano Pavarotti a singer, Frederic Chopin a pianist,” his friend the food writer Patricia Wells said of him.

Robuchon was born in Poitiers, the son of Henri Robuchon, a mason, and Julienne (nee Douteau), a housewife. He began cooking at an absurdly young age, at the seminary in the village of Mauléon, Deux-Sèvres, which he entered at 12 to be trained as a Roman Catholic priest and where he helped out in the kitchens. (In his pomp, Robuchon was known as le moine – “the monk” – in part because of his early experiences at the seminary and in part in recognition of his extraordinary dedication to his chosen path.)

He began his apprenticeship proper at the Relais du Poitiers at the age of 15. At 21 he travelled through France, learning about regional dishes and ingredients. This experience provided the basis for the gastronomic refinement of his mature years.

Remarkably, in 1974 at the age of 29, he was appointed head chef of the Hotel Concorde La Fayette in Paris, in charge of 90 chefs serving a thousand dishes a day. In 1976 he won the Meilleur Ouvrier de France competition. In 1981, aged 36, he opened Jamin in the Rue de Longchamp in Paris, where he was awarded three Michelin stars in 1984, and where he began to create his international reputation. In 1989 he was named the “chef of the century” by two of France’s arbiters of culinary taste, Henri Gault and Christian Millau.

Jamin became a place of gastronomic pilgrimage. The dishes and the experience of eating there will stay with anyone lucky enough to have done so. As a restaurateur Robuchon brought open-mindedness, creative genius and a drive for perfection. The level of brilliance achieved at Jamin could not have been achieved without a certain rigour and exactitude. Those chefs who worked in Jamin’s kitchen, including Gordon Ramsay, Michael Caines, Tom Aikens and Richard Neat, have borne witness to Robuchon’s ferocious discipline in the kitchen and to the regimented cooking process.

While the dishes were visually brilliant, technically flawless and a joy to eat, Robuchon had little time for the frills and furbelows, and stifling atmosphere, that traditionally had characterised French fine dining. The atmosphere in the Jamin dining room was notably relaxed, the staff as engaging as they were expert, and it was not unknown for an appreciative guest to be offered a second helping of a dish that they had particularly enjoyed.

Robuchon was no food snob. He was shaped by the radical ideas of nouvelle cuisine, but his early experience with French regional cooking opened his eyes to the potential of ingredients that were not usually part of the haute cuisine repertoire. Although he is most famous for having elevated mashed potato to high art by adapting Fernand Point’s axiom of the secret of French cooking being “du beurre, du beurre et encore du beurre”, he also combined caviar with cauliflower, truffle with garlic and pigeon with cabbage. He brought an earthy quality to the refinements of nouvelle cuisine. “You don’t need expensive or exotic ingredients to create a great cuisine,” he said.

He opened an eponymous restaurant in 1994 that was promptly named the best in the world by the International Herald Tribune. But the following year he closed the Restaurant Joël Robuchon and retired. He had seen too many of his contemporaries burn out or die because of the exacting nature of their profession.

A man of restless energy and broad sympathies, a few years later, in 2003, he opened L’Atelier de Joël Robuchon in Paris, a refined form of bistro, with a no-booking policy, counter service, stainless steel cutlery, glass (as opposed to crystal) and dazzling dishes. He was inspired by a demand for great food in less formal eating surroundings and the fact that some of his talented young proteges found it difficult to raise the money to start their own establishments without the name of a high-profile backer.

The first atelier (meaning, literally, workshop) was greeted with almost hysterical acclaim and long queues. It was soon followed by other Robuchon establishments in cities including Bangkok, Las Vegas, London, Macau, New York, Shanghai and Tokyo, each incorporating local ingredients and techniques into what is, essentially, classic French batterie de cuisine. At the most recent count, there are 26 ateliers, tea salons and bars which have been awarded a total of 31 Michelin stars between them, including five with the Michelin maximum of three stars. At their peak there were 32 Michelin stars, the most to have been held by any single chef.

In The Man Who Ate Everything, the American food writer Jeffrey Steingarten quotes Robuchon as saying “Ah, les frites. I know nobody who does not go nuts in front of a plate of crispy French fries.” He believed in making food accessible, informal and sociable, a philosophy that informed his books and subsequent television shows such as Bon Appétit Bien Sur, which ran for a decade on French TV.

In person Robuchon was modest, even quite shy, but with a lively sense of humour. Behind that lay a steely reserve and a clear sense of purpose. He always said that there was no such thing as a perfect meal. “There’s always something that could be done better.”

He is survived by his wife, Janine (nee Pallix), whom he married in 1966, and their children, Sophie and Louis.

• Joël Robuchon, chef, born 7 April 1945; died 6 August 2018

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.