“A brand exists first and foremost in the mind of the consumer. It may live as long as it is remembered. The logic of brand revival or recyclability is that some brands are buried in consumers’ psyches and as such may still have value. These ‘dormant’ brands are more likely to gain readier acceptance by consumers than would a totally new brand, and at a much lower cost…capitalising on an established heritage…” (1) Mihailovich & de Chernatony.

Article and exclusive video interview by Philippe Mihailovich – HAUTeLUXE.net & Caroline Taylor

The awakening of dormant luxury brands is now a new phenomenon but it has always been more common for investment funds to seek such names in fashion e.g. Vionnet, Jacques Fath. Many, such as Worth, Jean Patou, Chanel, Balenciaga were kept alive primarily due to their perfume businesses. LVMH billionaire Bernard Arnaud bought the luxury luggage ‘sleeping beauty’ in 2010 and is slowly expanding the maison across the world after 30 years of ‘sleep’. Britain’s Penhaligon’s ‘barber’ perfumery too was brought back to life after over 30 years of silence and has proved a big success.

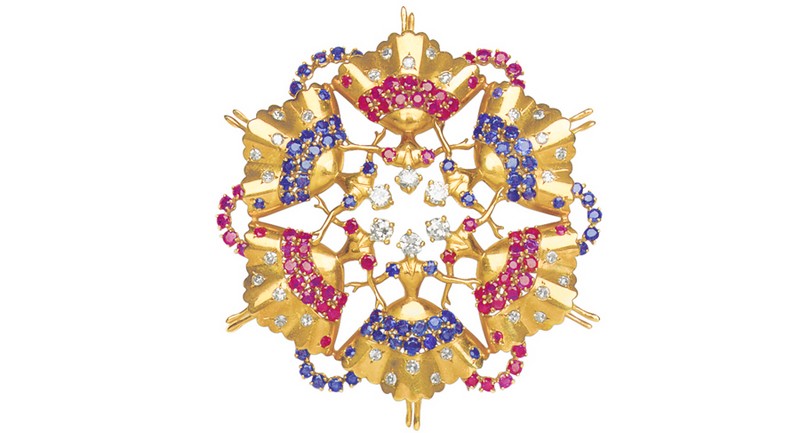

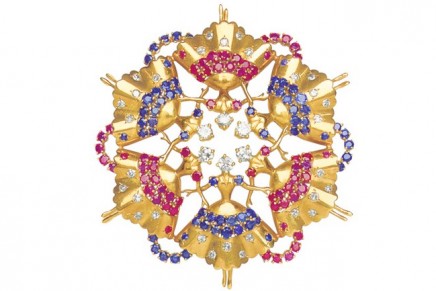

The John Rubel story is quite different. First born in Budapest as Rubel Aba and relocated to Paris’ rue Vivienne in 1915, the Rubel brothers soon established themselves as one of the most extraordinary craftsmen. They almost instantly became a preferred workshop, alongside the Verger brothers for the prestigious Van Cleef & Arpels who would exhibit at High Jewellery fairs in Paris and New York proudly displaying the names Rubel Frères and Verger alongside their own (2).

In those days, the houses of Cartier, Chaumet, Boucheron and others on the Place Vendôme did not all have well defined brand DNA codes and were very open to workshops offering them creations. In fact, as Sophie Mizrahi-Rubel, President, heir and creative head of John Rubel explains, “the big houses did not have the strong identities that they have today”. As with the major jewellery houses in China, one could easily swap the signage of the houses around and we would be hard pressed to notice.

The concept of ‘Maison’, where the house controls everything from the beginning through to the end, with no sub-contracting, was something few houses were in a position to do. As such, the Rubel Brothers grew in fame alongside Van Cleef & Arpels and their shared favourite designer Maurice Duvalet and by 1939 they had agreed to move to New York with VCA where the new centre of gravity for jewellery had shifted.

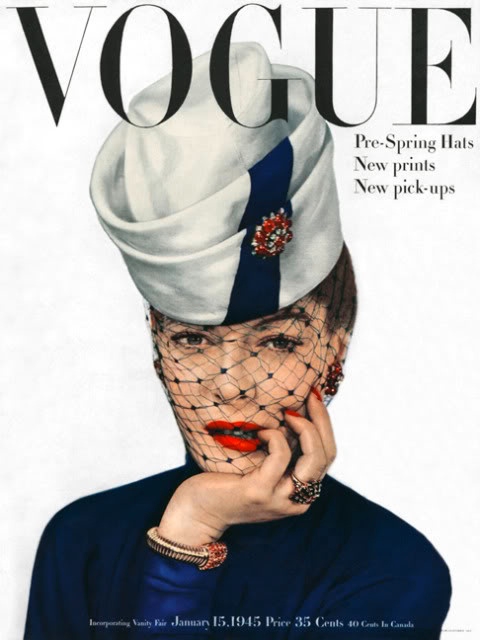

Some of the most sought-after antique jewellery today would be the exceptional pieces bearing the both the names Rubel and VCA and if anything has kept the Rubel name far from being forgotten, it is the antique jewellery connoisseurs and leading auction houses of the world. By 1943, Sophie’s great uncles, Jean and Robert Rubel had opened their own ‘maison’, John Rubel in the prestigious 5th Avenue close to the Savoy- Plaza Hotel, a move that clearly brought their collaboration with VCA to an end.

Did Sophie simply inherit the successful family business?

Sophie was born in France to a father who was a leading diamond dealer and a mother who specialised in precious gems. She was clearly born with jewellery in her veins and had been very inspired by all in the family to the extent that she already had the confidence as a student at University, to help modify bridal rings for friends and others. She later went on to study gemology and before long, was calling on houses on the Place Vendôme offering her sketches to VCA, Boucheron and the like, just as her great uncles had done, except that their business no longer existed.

Before long the famous houses were buying her designs and production of at least ten to twenty pieces – note that the houses did not have chains of stores worldwide at the time and internal creative directors planning the collections, by price point, in advance. Mizrahi-Rubel was then approached by LVMH’s Fred Jewellers to work for them full-time which she did for a number of years before joining Cartier and later Mauboussin. Unlike the fashion industry where Lagerfeld can work for Chanel, Fendi and his eponymous label, in high jewellery it viewed as a conflict of interest.

With Mauboussin and chasing mass-market sales for a faster turnover growth, and other Place Vendôme houses opening retail outlets at the speed of mass-market brands, Sophie could see that connoisseurs at the high- end of the business were fast defecting to lesser-known independent jewellers, the field she loved so much.

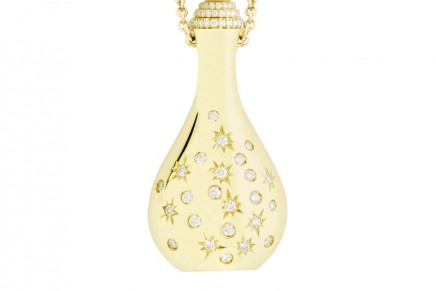

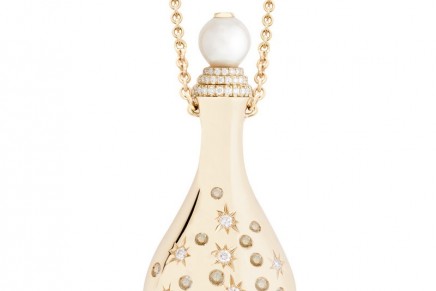

It was time for her to once more design exceptional, rare and timeless pieces driven by creativity or by what the stone requires rather than in accordance with a marketing plan. It was time too, to resurrect the family brand and she had clearly earned the right to do so.

Unlike the ‘sleeping beauty’ luxury houses mentioned earlier, this one has the authenticity of having a true family member behind it. Perhaps only Fabergé comes close to sharing such a story and even won the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève award in 2015. Sophie Mizrahi-Rubel is certainly on track to be a Haute Joaillerie award-winner for house of John Rubel in the near future.

1. Mihailovic, P. and de Chernatony, L. ‘The Era of Brand Culling: Time for a Global Rethink’ The Journal of Brand Management, Volume 2, #5, April 1995, pp 308-315;

2. Jean Jacques Richard, “L’Histoire des Van Cleef et des Arpels” 2010.