Until recently, one of the best British postwar ceramics collections was to be found on a council estate in east London. “It was a bit like walking into a reliquary,” says the ceramicist Annie Turner, a regular visitor to the two-bed flat. “You’d go into a pretty brutal-looking 1970s building and up a dull concrete stairwell and think, ‘Am I in the right place?’. Then you opened this door, and it was like entering another world.”

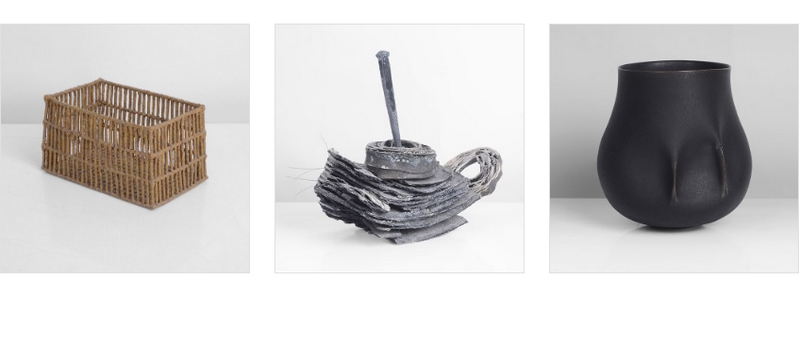

Behind that very ordinary front door was a treasure trove. Mostly British, French or Japanese, around 1,200 ceramic works clustered on shelves, grouped on tables and desks, and even used as planters on the tiny balcony. Among the objects were key pieces by Lucie Rie and Edmund de Waal, and contemporary works by Turner herself, and Sara Flynn – two award-winning artists whose prices have recently risen sharply.

This collection belongs to Michael Evans, a former mechanical engineer and local government officer, who has been known by his Buddhist name Dayabandu since his ordination in the early 2000s. Dayabandu’s interest in ceramics started 60 years ago when he used to visit two maiden aunts after church and admire their Doulton Lambeth stoneware pots. “They said they’d give them to me as soon as I bought my own property,” he told the i newspaper in one of his only interviews, back in 2004. The aunts kept their promise – though soon that property was more the home of the ceramics than Dayabandu. “They allow me to live with them,” he said. “People think I live in a store room.”

But many of the pieces are coming to auction this month. Dayabandu has suffered from increasingly severe vascular dementia, and the collection – instead of being a pleasure – has become a burden.

“He’d started getting concerned about it around 10 years ago, the same time his behaviour became more eccentric,” says his friend Clive Barnett, a textile designer who lives in Suffolk. “He knew he was becoming unwell. He wanted the work to stay together, but he couldn’t find anyone to take it on as a whole.” Indeed various museums were happy to cherry pick; no one wanted the job lot. “He was very knowledgeable,” says Barnett, “but we never quite understood why he bought certain things.”

Dayabandu’s friends describe him as anything from focused to intense to obsessive. His delight was in the ceramics themselves rather than their value or maker’s reputation. As he said: “I don’t buy for investment, I only buy what I like. I know people who regard their collection in financial terms – for the names on the bottom of their pots. For me, that’s not collecting for the right reasons.”

Once he’d retired from his life in local government, the suit and tie was abandoned for jeans and leather jacket. He moved from Leicester to Sandwich in Kent, where he took a part-time degree in fine art at Canterbury and finished with a first.

According to Barnett, his Buddhism followed a chance meeting with someone on Sandwich beach not long after the ending of a long relationship. He sold his house and downsized to the flat partly to release money to continue collecting, and partly to be near the London Buddhist Centre in Roman Road. He ate his lunch most days at the Cafe from Crisis in Commercial Street, where homeless people and ex-offenders are trained in catering. “Not the sort of staff you get everywhere – he liked that,” says another friend, Martin Pearce, a ceramicist, based near Battle.

“He never did anything by halves, once he was interested he got really involved,” continues Pearce. “To be honest, he could be abrasive. He’d come to see me once or twice a month in my studio when I was still working in London, and criticise my work. But if he saw someone who was struggling or needed advice, he’d really take it upon himself to sit down with them, and spend time talking it all through.” Turner, another beneficiary of his time and interest, says she would spend a day at a time at his house. “We’d have green tea in beautiful hand-thrown tea bowls – everything was handmade,” she says. “He’d tell great stories about all the work in the flat; he’d never buy anything that didn’t ‘speak’ to him.” His preference veered towards the natural, not the decorative, ceramic tradition; one can see the appeal of Turner’s exquisitely controlled and austere work inspired by the natural fragments she collects from the River Deben in Suffolk.

Once when she was installing a six-part piece on his kitchen wall, and having trouble doing so, she recalls how he walked past and stopped in the corridor. “He just said: make sure you’ve got the nails exactly straight. He was an engineer – he could tell what I was doing wrong. But he just gave me the advice from a distance. It was kind, he didn’t want to make me feel stupid.” (The piece is in the auction, with an estimate of £800-£1,200.) Turner recalls the flat as full of big dark furniture. “There was even a big four-poster bed with curtains around it. He just wasn’t afraid to fill up space,” she says. “And maybe I shouldn’t say this, but there was always a big spliff, ready rolled for bed time. He often had a lot of pain,” she says. Martin Pearce says that “he loved the austerity of Annie’s work, the absolute control and the links with the River Deben”. Dayabandu went there often on Buddhist retreats.

After being given his aunts’ Doulton Lambeth pots, he went on to collect Moorcroft – 20th-century British hand-painted pottery with vibrant high glazes – and then, having become increasingly enamoured of more contemporary works, he sold the lot. Moorcroft had become sought after, and it was a handy way to finance this new strand of acquisition.

“He liked being able to visit the potters, and going to fairs and open studios and talking to the makers,” says Pearce. “In a way, he was really interested in people.” The gallerist Matthew Hall, of London ceramic specialists Erskine Hall, agrees, adding: “He was always looking for the connection to the maker, an entry point to the life behind the work.” Hall also visited the east London flat and remembers looking at the Buddhist shrine that Dayabandu had created there. “There was one object, a brick from the exterior of a Buddhist temple that was at least 1,500 years old. It had the figure of a robed monk on the front,” says Hall. “But then he picked it up and turned it over and there was the impression of the craftsman’s hand on the back. He put his own hand in that handprint. It made so much sense.”

Photograph: Courtesy of the artists

Marijke Varrell-Jones, the founder of MAAK, the auction house organising the Dayabandu sale, says that this won’t be the first time she has broken up a collection. “They are transient things in the end,” she says. “And you have to remember, these pieces didn’t start out all being together.” MAAK – which specialises in ceramics and has offered a very slick online platform since it started in 2009 – will be offering nearly 200 lots in the auction Unifying Eye: The Dayabandhu Collection, including some by Akiko Hirai, another rising star. “He came to my studio a lot,” Hirai says. “He was always looking for movement, for something kinetic and tactile in a piece of work.”

Dayabandu was amassing his collection in the noughties, a time when work by postwar practitioners including John Maltby, Ewan Henderson, Ian Godfrey and Gordon Baldwin was still affordable. “It’s a reminder that what counts in forming a collection is the depth of your eye and enduring curiosity, not the depth of your bank balance,” says Hall. “He didn’t spend excessively on a single item.” So he would most likely be rather surprised by the results that are likely to emerge in May. Works by Lucie Rie have sold for upwards of £150,000 in the last few years; John Maltby and Ian Godfrey are highly sought after by younger collectors including Jonathan Anderson, the creative director of Loewe, who has himself found a passion for pots. “We saw a real change around 2016,” says Varrell-Jones. “Our clients used to be couples of a certain age, who’d retired with a disposable income. Now it’s younger collectors who want to live with handmade objects. And besides, there’s room on a bookshelf for a pot.” Or for 1,200 of them, if you happen to be Michael Evans.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.