Assemble

When Tate Britain director Penelope Curtis called Assemble to inform them they had been shortlisted for the Turner prize, whoever answered the phone didn’t know who she was – and anyway, they were too busy getting on with their work to talk to her. When the message finally got through, far from jumping with joy at having achieved the pinnacle of their artistic careers while still in their mid-20s, the 18-strong architecture collective sat down and had a serious discussion about whether they should accept the accolade at all.

“We were concerned that the community housing project we are working on in Liverpool would suddenly be seen as ‘art’,” says Lewis Jones, momentarily downing tools on the building site in Toxteth where the group is busy transforming a street of long-vacant terraced houses into affordable homes for a community land trust. “We decided we would only accept the nomination if we could use it as a platform to actually help move the project forward – and it’s really given it a boost.”

Beyond being flooded with phone calls offering commissions for everything from a house extension to a luxury hotel (none of which they have had the capacity to take on), the Turner prize limelight has boosted fundraising to help renovate further houses in the street, five of which have been completed so far, now let out at social rent.

Assemble recently established the Granby Workshop in the area, a social enterprise to train local young people to make furnishings for the new homes – from sculptural fireplaces to ornamental ceiling roses and doorknobs – products that are likely to loom large in their installation at the forthcoming Turner show at Tramway in Glasgow.

“We didn’t want to just use the exhibition to tell the story,” says Fran Edgerley, who has been co-leading the project in Liverpool with Jones. “We’re trying to use it as an opportunity for visitors to be able to play a part in supporting the ongoing rebuilding of the neighbourhood.” By the sound of it, gallery-goers might well be able to walk away with their very own little piece of Toxteth.

The group’s work in Liverpool is the most substantial project they have embarked on since they came together five years ago, as a bunch of recent graduates, to build a temporary cinema in an abandoned petrol station in east London. One pop-up led to another, and they attracted the attentions of the Olympic legacy team, who soon arranged for Assemble to occupy an abandoned warehouse in Stratford, east London – now reborn as their HQ, Sugarhouse Studios.

It is a thrilling workshop, bursting with tools, models and full-size prototypes, with chunks of “paper-crete” lying next to fragments of “rubble-dash”, just two of the intriguing hybrid materials the group have invented for their recent projects, including temporary theatres, touring exhibitions and a new town square in Croydon. None of them has yet had time to even fully qualify as an architect, but that hasn’t proved much of an obstacle. They are currently working a £2m permanent gallery for Goldsmiths, a group of artist’s studios in west London and a community garden for an estate in Poplar.

So has the Turner prize nomination changed them?

“There hasn’t really been time for a huge amount of soul-searching,” says Jones. “We’ve been mostly just getting on with it.” And, with that, he and Edgerley both get back to building – there are five more houses to finish, never mind the opening of the Turner show.

Oliver Wainwright, architecture critic

Nicole Wermers

When I first see the fur-coated chairs of Nicole Wermers’s Infrastruktur, it’s hard not to imagine that a model hasn’t just left the set of a high-fashion shoot to have her lipstick touched up off camera. Such is my fashion-addled brain that I start to narrativise the scene – who is the model? She must be fierce; I wouldn’t dare move that fur coat; is it Anna Wintour’s?

But for the German-born, London-based artist this is all wrong, and she tells me as much quite firmly. The installation is not about fashion. Rather it’s about appropriating space in an urban environment. “I wanted to take a fleeting observation that anyone can make every day in a restaurant – people put their jacket on the back of a chair in order to claim them, to turn public property into their own private space.”

In fact the coat could never be moved even had I dared. It’s sewn on to the chair so that it becomes a part of it. “I wanted to make this temporary occurrence a permanent feature of the chair,” Wermers explains. So the point isn’t just to mimic the gesture but to turn it into something else. This idea is echoed elsewhere in Infrastruktur. She has made ceramics based on the temporary signs put up on lampposts for missing cats with detachable phone numbers.

In Untitled Chairs the lining of each fur coat (sourced from eBay) is removed and replaced with a silk that tones beautifully with the newly upholstered seat on versions of Marcel Breuer’s Cesca chair. The artist shows me two that are mid-construction. The hemline is hanging a little too near to the floor on one (a proportion issue I can relate to) but it will be fixed when the backrest is raised.

In fashion, fur symbolises status. But the 44-year-old artist is clear that her work isn’t about power and class. “Fur isn’t always associated with luxury. You haven’t looked properly: a couple of them cost the staggering amount of £40!” What fur signifies for Wermers is a strong physical presence (“It’s a dead animal at the end of the day”) which in turn gives off an invisible forcefield – an idea the artist has long been interested in.

The play between the fur and the tubular steel feels very glossy interiors magazine to me. Wermers describes the fabric combination as a “well-rehearsed conversation” in modernist design, citing Eileen Gray’s E-1027 house. So I’m not totally wrong there. But I am well off the mark to picture models slinging furs around. Wermers’s work isn’t concerned with relationships between people who have left the scene. Hence the chairs are placed at an unnatural 90-degree angle to each other, more furniture shop than cafe. “For a second the chairs were almost named after Fassbinder actresses, but that would have emphasised narrative. And I really wanted to emphasise infrastructure.”

Imogen Fox, fashion editor

Bonnie Camplin

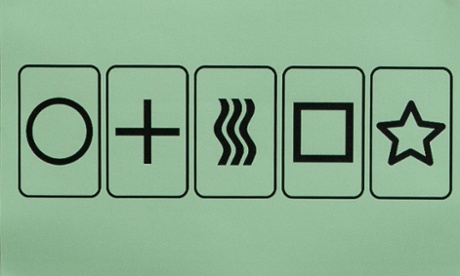

Bonnie Camplin is sitting on a stool in the kitchen of her flat holding up a Zener card with the symbol facing towards her. The cards – which bear pictures of waves, squares, circles or plus signs – are used to conduct experiments in extrasensory perception. Camplin furrows her brow and closes her eyes. I’ve to guess what card she’s holding. “When you get it right,” she asks, “what is your mind doing? What is my mind doing?”

Camplin believes in ESP even though she knows most people do not. Why shouldn’t someone be able to tune into the thoughts of another? Scientists have plenty of reasons why not. And when an experiment suggests someone aced an ESP test, there is always another explanation: the test was run badly, the result was a fluke, someone cheated. No one read anybody else’s mind. On that, most people tend to agree.

Camplin was shortlisted for the Turner prize for the Military-Industrial Complex, a study-type room arranged to explore the idea of “consensus reality”. How does a society arrive at common beliefs? And what is lost when ideas become marginalised?

On the wall is a sheet displaying five Zener cards. Elsewhere are images taken from the psychology department at Goldsmith’s University in London, where Camplin lectures in fine art. In those, a baby wears a hairnet of electrodes: an attempt by scientists to read infant brainwaves. The experiment looks eminently sensible: in our society, after all, science is regarded as an authority.

And there are good reasons why. Scientists build models of reality by proposing theories and testing them to destruction. It is about finding patterns in data that are corroborated by others until the chances of them being false are minuscule.

Camplin wants to embrace a more uncertain reality. Science – and other institutions, education included – have a constricting and standardising effect, she says. They make reality too rigid. “Making laws is a demand for certainty. In nature there are no laws, only habits. The demand for certainty gives us a calcified reality.”

Patterns flow through Camplin’s work. The artwork features the 1968 book Towards a Poor Theatre, by Jerzy Grotowski. The innovative Polish director based his theatre lab on the Danish institute founded by Niels Bohr, a leading figure in quantum theory, which so embraces uncertainty that it says two objects can exist in two places at once. Bohr was smuggled out of Denmark to avoid Nazi arrest in 1943, and became involved in the Allied atom bomb project, an example of the iron triangle of legislature, armed forces and military firms that became the Military-Industrial Complex.

A dozen or so books and articles lie on a table. Among them are five testimonials from people with fantastic stories. One tells of meeting with extradimensional beings, of travelling to Mars, of watching galactic wars rage. So does another. And so does the next. There is a pattern here: the individuals share a subjective reality. They corroborate each other. They have reached their own consensus reality.

“The proposition,” says Camplin, “is that I am open to the truth of these testimonies. Does that mean I’m mad? I’m not trying to get a message across. It’s about a dialogue. I don’t see art as a mouthpiece for my opinions.”

Ian Sample, science editor

Janice Kerbel

Doug is a 25-minute, nine-movement work for six singers that has been performed in its complete form precisely once, at Glasgow’s Mitchell Library. There was no public recording, nor does Janice Kerbel intend one. When I meet the Canadian-born artist, she’s not yet sure how to present the piece for the Turner prize exhibition: what will the visual representation of Doug become in the Tate’s galleries, apart from a handful of performances from the same team who gave its premiere?

In contrast to the classical music world’s obsession with trying to find visual expression, Doug is stark in its simplicity. The six singers wear the austere black mufti of the contemporary music ensemble, they stand behind their music stands, the conductor raises his hands, and they sing the notes printed on the scores in front of them. Kerbel, it seems, is consciously making a musical composition in Doug, not trying to make a hybrid of sound-art experimentalism, nor to splice new music and new visuals in some hipsterish fusion.

“The work is entirely about how it sounds,” she says. That rigour is precisely the point. “Music was a completely unfamiliar language to me when I started work on Doug. And it’s important for me to be obedient to an existing language, to inhabit the form very strictly and very rigorously.” So much so that she tells me she’s the proud conqueror of the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music’s grade 3 theory exam. “I was the only person older than about 14 sitting in my row in some huge hall near Westminster.”

She’s delighted with the “distinction” she was awarded, but says ta little knowledge is a dangerous thing: “When you start out knowing nothing at all, you’re not limited by not knowing what you don’t know. Now I know a little more, I probably couldn’t write another piece of music.”

In composing Doug, Kerbel was approaching the arcane languages of music, its notation, its performance culture and its rituals, with the perspective and insight of the outsider. That’s an approach she’s used before: writing the commentary for a fictional baseball game in Ballgame (Innings 1-3), creating a new language solely through lighting effects in Kill the Workers, and inventing a holiday resort, real in every palm tree and coral reef in its online representation and its offers to prospective honeymooners and luxury travellers – apart from the tiny detail that the island doesn’t actually exist.

Which all poses the question: why did Doug have to be a piece of music at all? “I knew I wanted to write a work for voice,” says Kerbel. “There are these nine accidents that happen to Doug, and I needed an ensemble of voices to embody them, because no single human voice could encompass the range.”

Ah yes, the accidents. Kerbel’s text in Doug tells of a series of remarkably unfortunate events to which the protagonist falls victim (an early version of the Doug project summed him up: “I knew this guy once named Doug. Man, did he have some luck”). These include a bear attack, a massive object falling out of the sky on to his head, a lightning strike, a long drawn-out asphyxiation, a slip, a drowning; all written in poems of wildly differing size, shape, tone and verse. Why is it called Doug? Because of that joke, she says. “What do you call a man with a spade on his head? Doug.”

The idea of the accident runs through her work. “For Doug, I looked at physical comedy, cartoons. I have a kid and I’m always trying to stop him from having an accident. So the idea was on my mind.”

Kerbel was assisted by composers Philip Venables and Laurie Bamon, and the conductor George Chambers, who taught her to use the Sibelius music-sequencing program, and suggested how best to realise her ideas about the shapes, sounds, and dramas of her accident-prone antihero. She shows me the stages of her composition: graphs of note names and vocal register, scrolls of paper that mark her multidimensional attempts to fix and choreograph Doug’s accidents through the languages and mechanics of musical time from boxes of her own musical handwriting notation, too big for conventional music paper, to the finished score, as polished and finessed-looking as any product of contemporary notated music.

The resulting work was hailed by the few who heard it as a piece that could stand alongside other new vocal compositions, but Kerbel is less sure of Doug’s next stage of life. “Doug was clearly produced for a specific context, and it is in this context that I can best try to understand it.”

I’m one of the lucky ones who has been granted access to a private recording of Doug. What it reveals to me is that Kerbel’s work creates an imaginative space that does something more than simply depict the accidents that befall the hapless Doug. Instead each piece (even the climatic Slip, which sets the haiku-like “Heel on peel / To seal the deal. Feet to sky / Life slips by” in a single moment of vocal slippage) dramatises its accident and turns it into a musical object. In other words, Kerbel is doing what any real composer does, manipulating the stuff of musical time through her handling of the space of musical notation. In that sense, composers have always been artists. Perhaps the Turner should be open to all of them next year?

Tom Service, classical music writer

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.