The best place to watch the world’s money pouring into the UK isn’t at the London Stock Exchange or in the offices of the City’s magic-circle law firms, but holding a cup of tea in one of a handful of hotel lobbies. In the Dorchester’s long, narrow Promenade bar one evening in August, most of the high-backed sofas are occupied by Middle Eastern guests, some of them drinking with friends and families, others sitting next to lawyers and fixers, who listen and scribble. Occasionally, something is signed unsmilingly; hands are shaken.

The Promenade is a public space with privacy designed in – the height of the sofas, and the faux-marble pillars, make it difficult to see who is talking to who. The guests order from the bar menu – beef sliders for £21, £770 for a 50g portion of beluga caviar. An order comes in for a £570 bottle of NV Krug Rosé and, unlike at a Chelsea nightclub, no fuss is made.

A few decades ago, London’s grand hotels were shabby and beleaguered, their rooms empty. Since the crash, without anyone in the real world noticing, they have found success in a new role: as the places where the capital’s new class of plutocrats like to do business; the unofficial bourses of London’s transformation into the richest city in the world.

“I do business with a Saudi client, and he comes over with an entourage of 70 people,” says an estate agent who has brokered a number of recent eye-popping property deals. “He has homes in London, but he does business in the hotels.”

The Middle East’s wealthiest men have grown so fond of London’s posh hotels that they have bought almost all of them. The Sultan of Brunei owns the Dorchester; Saudi prince al-Waleed bin Talal has refitted his Savoy, to the dismay of old-school visitors; and this summer the Barclay brothers sold their stake in Claridge’s, the Berkeley and the Connaught to a business controlled by Qatari sovereign funds, after the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority had reportedly offered £1.6bn.

Nowhere are the incredible inequalities at the heart of London more stark than in these hotels, where London’s two economic narratives – the influx of foreign cash and an epidemic of low pay – come together in the same room. The wealth magazine Spear’s noted, in an interview with a company that provides contract cleaners to the Dorchester, that a cleaner at the Park Lane hotel would have to work for 56 hours to be able to take an entry-level room for the night, before tax. It’s not just a useful metaphor for modern London; this bumping together of obscene wealth and its lowest service layer can throw up practical issues of its own.

The capital’s most luxurious hotels have always straddled the private and the public. According to The West End Front, a book by Matthew Sweet about the role of the hotels during the war, men such as César Ritz, who opened the Ritz in 1906, played a central role in persuading “the plutocracy and the aristocracy to do something to which they were unaccustomed – eat, drink, smoke and dance in public”. Sweet says that high-born women who previously only socialised in country estates and private town houses began to do so at the hotels: “There was a whole class of young British women who were allowed to have their first unaccompanied nights out at these places.”

On the other hand, they are places designed to feel like islands in the city, trading on their separateness from it. “They are these sequestered places – you are immediately separated from the outside world,” says Sweet. “They employ these strategies, like casinos in Vegas, to prevent you from noticing the outside world. The Dorchester has its internal boulevard – you are not looking out at Hyde Park. At Claridge’s, you are looking at the staircase, not London. The whole idea is to separate you from people outside, so you can enjoy yourself in this sort of citadel, unencumbered by the view of people who can’t afford to get in.”

The difference is that the hotels have arranged things – specifically Michelin-starred restaurants and multimillion-pound spas – so that their guests never have to venture out. If they want to occupy a green zone of affluence, away from the crowds and prying eyes, the hotels are set up to oblige.

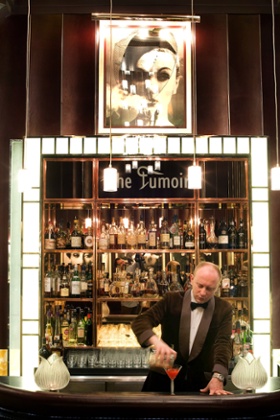

“They used to have terrible restaurants, they never had good service, they never had good spas, but then they realised they have to compete internationally,” says Josh Spero, editor of Spear’s. “Now they have the best restaurants in London, and the best spas. Global money is coming to London, and these hotels need to offer better service.”

This year, Simon Rogan’s Fera restaurant at Claridge’s was awarded a Michelin star. There is also the three-Michelin-starred Alain Ducasse at the Dorchester, the two-Michelin-starred restaurant at the Connaught, overseen by Hélène Darroze – named the best female chef in the world – and Marcus Wareing’s restaurant at the Berkeley, which has two stars. Other luxury hotels competing for the same guests, such as the Mandarin Oriental, also have Michelin-starred restaurants.

Being high-class islands that offer the best food, gyms and relaxation in the city, as well as providing a suite for the night, means guests who don’t want to leave don’t have to. Anecdotally, it seems some of the very wealthiest guests choose to go all in – doing their business in the lobbies, meeting their private advisers in their suite and booking up vast stretches of rooms for their entourages.

The estate agent says his wealthiest foreign clients always choose one of Claridge’s, the Dorchester, the Berkeley or the Connaught to meet. “Generally you will be meeting the people who work for them first,” he says. “They come here after Ramadan and take over a whole floor. Sometimes, they take one or two or three floors. I have seen that.” He says Saudi clients are more likely to do business in the hotels despite owning vast properties in London, in order to keep their private lives separate. “The Qataris will let you come to their homes, and some have their own offices now, but meetings still get done in the hotels.”

A Dorchester staffer says a Qatari guest took over the three big suites at the top of the hotel this year, hiring a personal chef for his long stay, and apparently spending more than £40,000 a night. “Everything happens upstairs,” he says – meaning that the guest never had to leave his floor.

In touch with the needs of their new guests, the hotel’s managers have put a manic focus on protecting privacy. Staff approached at several of the top hotels tell me they have signed confidentiality agreements preventing them from saying anything about what goes on in their workplace. One Dorchester staff member, who says he will be instantly fired if he is spotted speaking about his job on a nearby street, says that even the staff are not informed when certain, very private, guests stay. He says his colleagues have become good at guessing when a Middle Eastern sheikh is staying because the VIP booking desk, which handles the top guests, will put a British-sounding name down – “such as John Stewart” – when everyone in the hotel knows those kind of bookings are very rarely made by Europeans these days.

“UHNWs’ [ultra-high net-worth individuals] prime value is their privacy, and no institution that associates itself with UHNWs will want to be seen to have loose lips,” says Spero. “That is as true of their private banks and their lawyers as it is their hotels and their private members’ clubs – privacy is paramount. So if anything is happening at five-star hotels, which hotel manager is going to say: ‘Oh yes, please come and read about the guy who died in our presidential suite’?”

On the afternoon of Friday 1 May, a wealthy Kuwaiti guest by the name of Sultan Aldabbous, 38, was found dead in his room at the Dorchester, and two men were arrested in connection with the incident . The postmortem results were considered inconclusive and the coroner ordered further toxicology tests. Then, in August, the Metropolitan police said that the two men had been released without charge, and the death had been deemed non-suspicious. The coroner will set a date for the inquest soon. A spokesman for the Dorchester declines to give any further details, adding that the case is “now closed and of a private nature”.

It may rather appeal to a certain type of guest to know that hotels like the Dorchester can offer them almost as much privacy in death as they do in life.

A hotel worker tells me another story, this time of an alleged sexual assault at a luxury hotel (not one of those named in this article). The staff member – foreign and generally happy with his working life – meets me a few blocks from his workplace and asks if he is being recorded and if his anonymity can be guaranteed. Pockets are turned out, my phone switched off. He describes an acquaintance of his at a different hotel who says she was raped by the doctor of a wealthy Saudi guest last year. After the hotel’s security team and the police looked into it, no action was taken.

Establishing the precise details of the alleged attack is difficult, but someone who has intimate knowledge of the incident, and who asks not to be named for fear of losing their job, confirms that the complaint was made and that a full investigation was undertaken by the hotel’s staff, in cooperation with the police. Until now, though, nothing about the alleged rape has been reported.

The head of an agency that provides staff to several of the top hotels, again speaking anonymously, says that she will only supply bedroom attendants to hotels that have strict rules about never allowing a guest to be alone in a bedroom with a staff member. “If a girl is in the room, cleaning, and a guest walks in, what is the policy? I always ask that question, because I have to sleep at night,” she says. “If the guest walks in, they are vulnerable. I wouldn’t give them [staff] if their interest wasn’t to protect the girls, in any situation. If they say: ‘We leave it up to the girls’ – that isn’t good enough.”

In recent years, London has become a more segregated place, its reputation for rich and poor living cheek by jowl on the corners of fashionable streets eroded by cash-strapped councils selling off estates to developers and relocating poorer inhabitants to the margins – or out of the city altogether. The hotels of which the capital’s new cadre of foreign rich are so fond are now the places a middle-class Londoner is most likely to bump into an oil-state sheikh or a Russian steel tycoon – sitting across the lobby on a wedding anniversary tea or brushing shoulders at the restaurant. They are palaces that regulate contact and separation like early modern courts.

Their futures will now be dictated by owners probably more interested in trophy assets than bottom line. But the arms race to provide ever greater pampering, cuisine and luxury threatens to endanger their renaissance. “The word is that the Arabs are starting to find London a bit expensive,” says one leading concierge.

Not since exiled princes and visiting generals came to stay during the second world war have London’s most luxurious rooms-for-hire been so cosmopolitan – or so full up with guests worth whispering about. They offer unprecedented luxury and look after the capital’s most important guests with undoubted flair. Anyone wondering what is really going on in the old hotels these days, though, will have a hard job finding out.

- This article was corrected on 5 October 2015. We originally stated that Gordon Ramsay at Claridge’s had three Michelin stars. It is actually Restaurant Gordon Ramsay that has three stars; the Claridge’s restaurant only ever had one.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.