When Karen McCartney first stumbled across the title Superhouse for her new coffee table book, she worried it might sound a bit “flash, moneyed – vulgar even.”

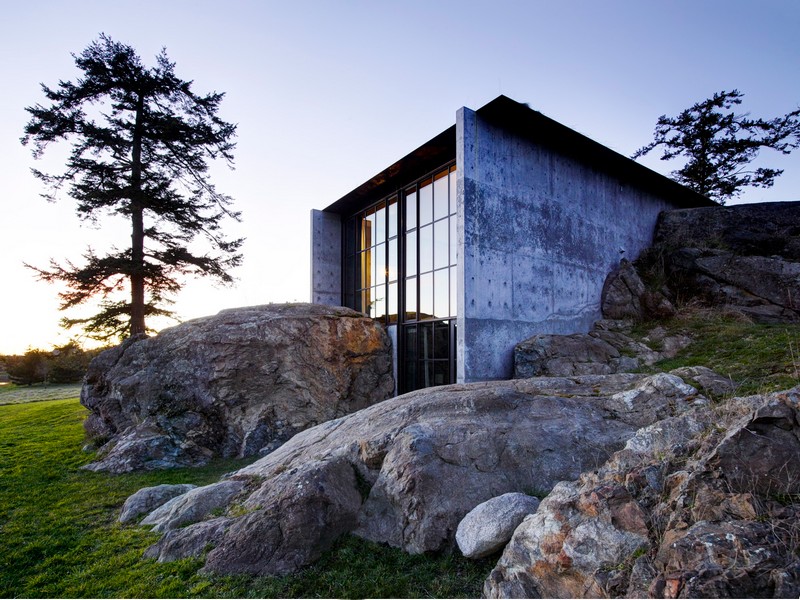

Then again, perhaps that is part of its appeal. Superhouse is unabashed property porn. Houses are photographed in luscious detail, ranging from the grand tumbledown arches of a restored 16th century English castle to a Seattle home built into a rocky outcrop.

Most urban professionals in cities like Sydney (where the median house price is 10 times higher than the median income), London and New York are unable to get on the property ladder without help . Let alone live in a house designed with the delicate curves of a butterfly wing, like one Victorian superhouse overlooking the wilds of the Bass Strait.

So why do Australians – and others – fantasise over these dream homes?

“We are always fascinated with how other people live and particularly the ends of the spectrum,” social researcher Dr Rebecca Huntley says. “So it might be with the same interest that we watch [the SBS documentary] Struggle Street and view some extraordinary house designed by an architect.”

Like a designer handbag or a car, our homes give us status and become an outward signal of the rank and standing we wish to project to our peer group.

But everyone’s idea of a dream home is different according to Neale Whitaker, editor-in-chief of Australia’s Vogue Living magazine: “My dream house is a spacious warehouse apartment in the inner-city with a roof terrace. I have no desire for a swimming pool, paddock or parking for five cars. Yours might be a waterfront mansion or a country homestead.”

Interiors can also be revealing. In The Secrets of the Bedroom, a chapter in Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Malcolm Gladwell relays a telling experiment.

Psychologist Samuel Gosling invited strangers to view the dorm rooms of college students. They had 15 minutes to look around and answer a series of questions about who lived there, ranging from how conscientious the occupant was to their emotional stability and openness to new experiences. He then compared their answers to friends of the students who were asked identical questions.

Surprisingly, the strangers were able to garner more information than the friends simply by looking at the students’ bedrooms. They instinctively drew on a mixture of “identity” claims (deliberate declarations of how we’d like to be perceived such as a framed university certificate or photograph with a celebrity) to “behavioural residue”, the aspects of personality we inadvertently reveal through our homes; for example a chaotic kitchen or a shoe rack organised in ascending colours.

“Forget the endless ‘getting to know’ meetings and lunches, then,” Gladwell writes. “If you want to get a good idea of whether I’d make a good employee, drop by my house one day and take a look around.”

“Whether it’s right or wrong, it does set an impression,” agrees Dylan Farrell, Sydney-based designer/creator of the Hamel+Farrell furniture collection and creative principal at interior designer Thomas Hamel & Associates. “You’re telling a story about yourself and the house. This,” he says, throwing his hands around the living room of his Sydney terrace house where knotty plant roots are artfully displayed in glass cases opposite Moorish-style art deco mirrors, “is like an instant resume – it’s a snapshot of who I am. You’re judging me based on what you are seeing here.”

It is no surprise, then, that we have a preoccupation with peeping through the keyhole into the lives of others. Television programs such as Renovation Rescue, The Block, and Relocation Relocation are booming, the Financial Times publishes a weekly At Home interview with a well-known person; interior design magazines are on every newsstand; and Superhouse, an exhibition coinciding with McCartney’s book, will soon be on show at the Museum of Sydney.

Similarly anyone can broadcast their homes to others through social media sites like Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest – often shot in soft muted lighting and flattering filters. We spy and consume, comparing, contrasting, and critiquing as we go.

In a wealthy society such as Australia – a country, as Whitaker puts it, which has a “love affair with real estate” – unspoken competition over our homes is rampant. This is a home owning democracy, says Huntley, and homes make up an integral part of “the great Australian dream.”

That dream, as in America, was founded on building a home from the ground up. Both countries were colonised with the promise of vast untapped resources and opportunity to create new lives on new lands (settlers, of course, conveniently ignored the native indigenous populations).

In the west, the relationship between a room of one’s own and how it defines identity remains strong. Yet aspirations differ from culture to culture. In high-density Hong Kong and Tokyo, for example, most families live in cramped apartments and a goal might not be ownership of a large house to entertain in but membership of a coveted social club.

Not here. In Australia, as affluence has increased and families have reduced in size, houses have only gotten bigger, many now endowed with open-plan kitchens, spacious ensuite bathrooms, and media rooms. Australia might be a beach and bush nation in the popular imagination, but in reality it is highly urbanised (nearly 90% of the population inhabit towns and cities). Despite apartments rearing up across inner city areas, most locals aim to live in stand-alone houses in sprawling suburbs.

Owning a property remains a barometer of success. While the financial crisis hit the British and American housing market hard, Australia didn’t suffer a large dip. There remains concern about a housing bubble but, as Huntley points out, “we haven’t lost our faith that the money invested in housing is the right investment to make.”

And while it’s unlikely that most people will design and build or do-up their dream home, they can incorporate aspects showcased in print media and on reality TV programs.

“People love looking at beautiful things and love to be inspired,” says Whitaker. “But they love it even more when the dream presented to them is potentially within their reach. That if they painted their walls a certain shade, changed their dining chairs, bought a new rug or re-tiled the bathroom, their home might just look like the pages of the magazine.”

While this means rampant consumption, it also means that design is becoming “less elitist and more democratic”, insists Whitaker. “[As] home improvement and renovation becomes within reach of all of us, there is a quest at the top end of the market to create homes that are ever more individual and bespoke.”

It was this quest that McCartney taps into for her book, showcasing houses that project a different way of living, something “beyond the everyday”, and with a connection to nature, an idea of retreat, a luxury of absence, or a beauty in form.

“It wasn’t just about grand scale and money,” she explains, sipping tea in her Sydney northern beaches house, which is designed by the architect Bruce Rickard. “It became about thought and originality and perspective, that allowed [these houses] to have a richness.”

The fantasy of the dream home may well be about securing financial security, showing off our status, splashing money, and marking our identity. Yet the best of the dream homes built – the ones that may last for centuries and will become part of our architectural heritage – are just as much about aesthetics, beauty, and daring design.

The test is whether in future generations these homes will be valued as classics, like English Georgian architecture or the brownstones in New York. Are they passing fashions or will they become integral to the culture of the country? That, after all, is something worth dreaming about.

• Sponsored by Sydney Living Museums. All content is editorially independent

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.