Since the advent of computer modelling in the early 1990s, architects have been able to conceptually manipulate not just the very large, but also the very small. Already, nanotechnology is found in the buildings springing up around us: in products such as self-cleaning glass, self-healing paint, and tougher steel bolts and cables. Chemicals company BASF, for example, produces Master X-Seed – a concrete additive containing nanoparticles of calcium silicate hydrate that cause the substance to harden twice as quickly.

Surprised? You’re not alone. Even the people who really ought to know about the presence of nanoparticles in building materials are often completely unaware of their existence.

Under the radar

A 2012 survey of UK designers and occupational health and safety advisers found that very few of the 322 participants believed nanotechnology had ever been used in one of their projects. They were probably rather shocked by the list of nanoparticle-containing products they were presented with afterwards.

A newly funded project led by Prof Alistair Gibb at Loughborough University aims to tackle this knowledge black hole, a status compounded by the fact that nanomaterials are not required to be listed under the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) regulations. The team’s work aims to identify and record the nanoparticles used throughout the construction industry.

“Some nanoparticles have been cited as generating health problems,” says Gibb, “but there doesn’t seem to be enough evidence to persuade governments to take specific action. It is just as important to establish that a product does not contain harmful particles, or that they do not become bioavailable through these processes such as demolition, as it is to find out that they do. We want to help society to take advantage of these ‘wonder materials’, but in a safe and healthy manner.”

The term “wonder material” is one we have heard before. Synonymous with asbestos – the 19th century material lauded for its ability to insulate against heat, fire and sound – the phrase rings alarm bells. By the time asbestos was proven to be toxic, it was concealed everywhere, from walls and ceilings to pipes and floor tiles. Like asbestos, could nanotechnology prove too good to be true?

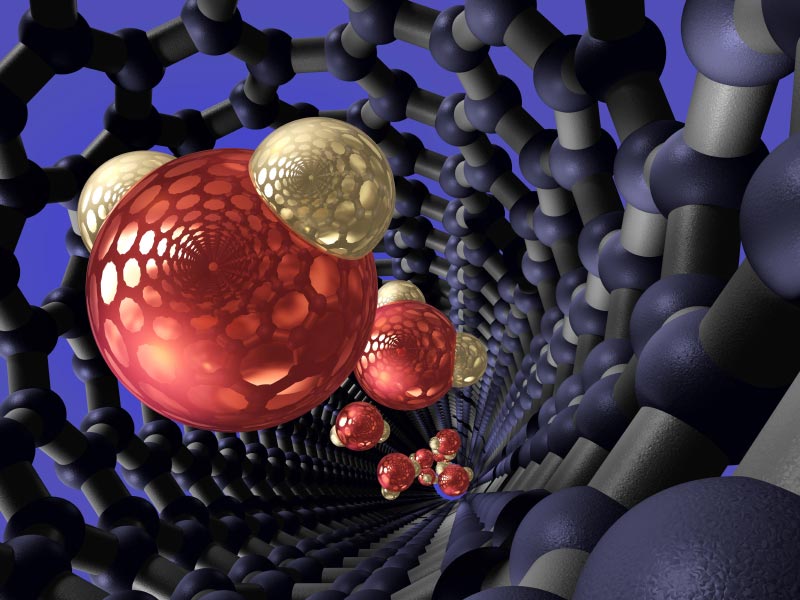

As Gibb states, there is significant research suggesting that some manufactured nanomaterials are hazardous to health. Carbon nanotubes – used in a range of products including ceramics, cement and high-strength steel – are one of those with a question mark hanging over them. Potentially toxic nanoparticles such as carbon nanotubes may remain harmless whilst embedded into the material, but the destruction of the material may make the nanoparticles “bioavailable” – meaning that they could be inhaled, ingested or absorbed through the skin.

Now, as back then, legislation simply cannot keep the pace with the rapid expansion of nanotechnology research and development. In the meantime, Gibb’s team are attempting to fill in as many of the blanks as possible. “Our work is aimed at increasing our knowledge so that we can apply prudence. If we know where nanomaterials are and record that, then if the research does end up proving the worst, we can do something about it in the future.”

Going green?

There continues to be a great push by research and industry to incorporate more nanotechnology into architecture, despite the evident disparity between the concerns of toxicity and nanotechnology’s ability to create a “greener” breed of buildings. A major selling point of BASF’s aforementioned Master X-Seed, for example, is that the supply of heat usually required to accelerate the hardening of concrete can be reduced or is no longer needed. This saves energy and reduces both carbon emissions and costs.

Dr Ivan Cole of Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) reports that some aspects of their nanotechnology research could actually reduce the use of existing toxins in building materials. “We are developing coatings for aluminium and galvanised steel, where embedded nano-capsules promote both the repair of the coating and repair any underlying metal corrosion. They could replace the current use of human toxins, such as strontium chromate, in such coatings.”

Back in the UK, the AVATAR (Advanced Virtual and Technological Architectural Research) group is keen for the construction industry to think creatively about the benefits that nanotechnology could bring. Founding director Professor Neil Spiller and his team are imagining and experimenting with a range of ways in which nanotechnology could contribute to a more sustainable built environment. “Traditional construction techniques rely on bulk manufacturing, which is often polluting, uneconomical, wasteful and energy intensive,” Spiller says. “We need to harness nanotechnology to survive on this planet. It’s as simple as that.”

AVATAR’s co-director, Rachel Armstrong, is looking to the potential of nanotechnology to truly radicalise architecture. “Nanotechnology will not just be incorporated into inert materials to give them different kinds of properties, but will also be combined with other technological media.”

Brigit Lau, spokesperson at BASF, agrees on the need to push forward the development of sustainable architecture by innovating with nanotechnology: “There is a strong demand for high-performance insulation systems, be it for new buildings or modernization of existing ones. Limited resources, world population growth and the urbanisation trend make it clear that future trends in architecture depend heavily on new materials and products.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.