On 30 September 2018, Kylie Jenner – Kardashian scion, businesswoman and owner of a world-famous pout – uploaded a photo to Instagram. In it, she posed beside a blacked-out Range Rover in a pink Katharine Hamnett jacket, cinched at the waist with a grey Chanel bumbag. Underneath, she wore black cycling shorts, white socks and chunky Joshua Sanders trainers in a silvery metallic finish. More than four million people liked the post, captioned simply: “happy sunday.”

In Leicester, a 20-year-old student Queentonia Ojeka studied the post closely. She liked the length of the blazer and how the shorts hit mid-thigh. Also, it looked comfortable. So Ojeka did what millions of young women across the country do every day: went online and purchased a tweed blazer from the American low-cost retailer Fashion Nova for $30 (£23), which she paired with £8 chocolate-brown cycling shorts from the British brand PrettyLittleThing. “I love Kylie Jenner,” Ojeka laughs. “As much as I hate to admit [it]. Her fashion is evolving, which is why I like her even more.”

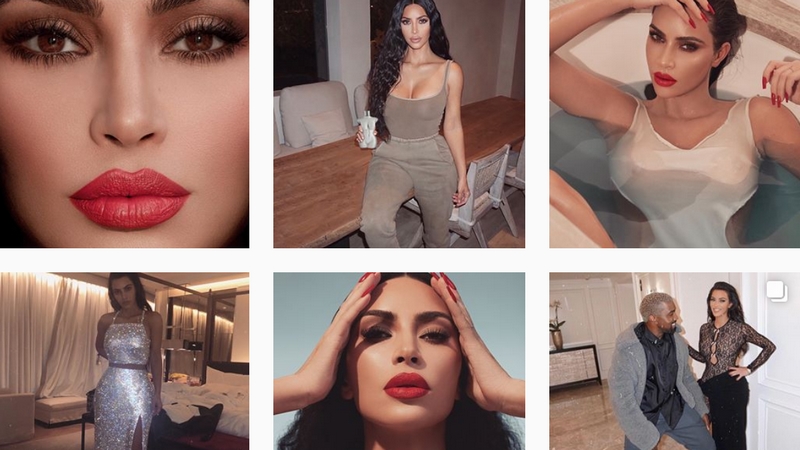

Corsets. Orthopaedic trainers. Crop tops. Cycling shorts. Cycling sunglasses. Sequinned slip dresses. Lace bodysuits. Neon. Latex. Thigh-high boots. These are all fashion trends the Kardashians have helped popularise internationally. In bedrooms across the country, women painstakingly contour, bake and overline their lips in an approximation of the Kardashian makeup aesthetic. In nightclubs, you’ll see Kardashian disciples teetering in Lycra bodycon and spike heels.

Clothing this growing army of Kardashian clones is a fast-growing industry of ultra-low-cost online retailers. There is PrettyLittleThing, Missguided, Boohoo, Nastygal and the US phenomenon Fashion Nova, but newer players including Oh Polly and MissPap are also entering the space. Browse these sites, and you will see yards of figure-hugging lycra and cheap lace in neon, pastel, or earthy tones. For the price of a large takeaway pizza (dresses hover at around the £15 mark, and sales are always on), you can own an outfit that – if you squint hard enough – could be from a Kardashian-Jenner’s Instagram post. It is a good time to be a model who resembles one of the Kardashians, too: lookalikes such as Lalla Rania Benchegra, who has modelled for PrettyLittleThing and appeared in campaigns for Fashion Nova, are in high demand.

For the uninitiated, the Kardashians rose to fame in 2007 with their reality TV show Keeping Up With the Kardashians, after the release of second-oldest daughter Kim’s sex tape. (The family had a certain degree of notoriety already thanks to the late Robert Kardashian’s involvement in the OJ Simpson murder trial: he was Simpson’s friend, and served on his legal team.) Just over a decade on, the family’s status as the Medicis of modern celebrity is assured: between them, they have a combined Instagram following of more than 536 million people, and Keeping Up With the Kardashians has run for 15 seasons.

But the Kardashians weren’t always an unstoppable global fashion juggernaut. For years, they dressed in clothes you could buy in the average department store (their Kardashian Kollection was stocked in the US retailer Sears). Then, in 2012, Kim began dating Kanye West, who introduced her to designers including Olivier Rousteing at Balmain and Riccardo Tisci at Givenchy, as well as his own Yeezy brand. Gone was the polyester animal print and in was an athleisure-inspired silhouette. The West association arguably conferred credibility upon the family: by 2014, Kim was gracing the cover of Vogue in a strapless Lanvin wedding dress.

Back then, Instagram was in its infancy, but as the Kardashians’ stars rose within the high-fashion firmament, they cemented their celebrity status on social media. In 2012, the year Kim began dating West, she reached a million followers on Instagram: just seven years later, she would top out at more than 125 million. “They are very influential, just because of how much they’re talked about,” says Ojeka. “They’re spoken about; they’re on everything.”

The Kardashians patronise such brands as Boohoo and Fashion Nova, switching allegiances for monetary reward. According to the Instagram marketers Hopper HQ, a single post on Kylie’s Instagram will set you back a cool $1m; you can have Kim for $750,000. Brands that affiliate themselves with the Kardashians, whether officially or unofficially, experience mega-growth. Fashion Nova was the most-searched-for fashion brand on Google in the US in 2018. Boohoo’s UK sales rose by a third to £180m in the last four months of 2018, with its strong performance credited in part to a successful collaboration with the eldest Kardashian daughter, Kourtney, who has long championed the brand. (Sales increased 95% at PrettyLittleThing, and 74% at Nasty Girl in the same period.) The success of such companies comes as established players in the UK retail market struggle: Asos recently posted a shock profit warning, and sales are also in decline at Topshop. Even negative press can’t scupper their mega-growth: Boohoo was recently criticised for selling real fur jumpers it had advertised as fake.

What makes these retailers so successful? Dr Jonathan Reynolds, a retail and e-commerce expert at the University of Oxford, says they have some distinct advantages. As most are online-only (Missguided has two physical stores in the UK), they don’t pay for retail space, which means they can have shorter product runs and test new products out. “When you’ve got a store, you have to fill it with goods, which means you have to have a big inventory. So they are a much more agile kind of business, which seems to chime today with the fairly instant culture we have.”

The pulsating sun at the centre of this new fashion solar system is Instagram. Fashion Nova’s network of more than 3,000 influencers, including Kylie Jenner and Cardi B, are critical to its success. They post pictures of themselves wearing outfits that are immediately available to purchase online. If the item sells, great; if not, the brand moves on to the next thing, unencumbered by large amounts of stock. On Fashion Nova, you can currently buy a white polyester minidress modelled by Kylie herself for $32.99, plus postage. And if your brand can’t afford to drop millions on Kardashian endorsement then in-house design teams can produce knock-offs of designer items worn by celebrities within days. After Kim’s aesthetic? A neon-pink minidress similar to the one she wore to Kylie’s 21st birthday party could be yours, from Boohoo, for just £4. “I’ve seen girls wearing that pink dress out on the town,” says 25-year-old handbag designer Lauren Levin, from Leeds. “It’s a very popular style.” Levin frequently hears from customers wanting a Kardashian look. When Kim toted a neon bag in August 2018, Levin had so many requests, she created a replica. “They definitely have a massive influence on my generation.”

“They can sell anything,” agrees Pamela Church-Gibson, the author of Fashion and Celebrity Culture. She describes them as being at the centre of an “alternate fashion system”, which “is not people looking at pictures of fashion shows and interpreting the trends themselves, it’s women wanting to look a certain way, social media providing those images, and new retailers, particularly retailers that use social media a lot, like Boohoo, picking up on these trends and bucking it to their advantage”.

“When it comes to clothes, they know how to dress,” says 23-year-old Tanyel Hassan, of the Kardashians. “If there’s an outfit they’ve got on for, say, thousands of pounds, I go on Boohoo or Missguided to see if I can get one that’s inspired by that, but cheaper.” Hassan, a teacher from east London, spends £50 a month on clothes; if she is going on holiday, she will pick up a new wardrobe for £300. When Kim wore a black lace bustier at Paris fashion week in 2016, Hassan purchased a copycat from Boohoo for £12. When Kylie posed in a bodycon, calf-length dress in September 2018, Hassan bought a £20 Missguided version.

Yet the Kardashians don’t just sell clothes, but a way of being. “The Kardashians live aspirational and over-the-top lifestyles,” says Amanda McClain, author of Keeping Up the Kardashian Brand: Celebrity, Materialism, and Sexuality. Dress like a Kardashian, and you can approximate a lifestyle otherwise beyond your reach, with low-cost retailers bridging the gap. “It makes it so much easier to be able to have even a little glimpse of being in their shoes,” says Ojeka.

For some young Kardashian fans, social media can be the most important part of a night out, says Emily Hall of social influencer experts the Goat Agency. “They’ll have full-on photoshoots before they go out, because they’re looking for that approval from a wider audience.” But when your wardrobe is reverse-engineered to maximise likes, posting the same outfit twice is heresy.

All the women I speak to concede there is enormous pressure to look good online. “I do think it has a negative effect,” Levin says. “Because when I post things on social media and I don’t get as many likes as the photo before, I think, what’s wrong with me? I’m very aware there’s a big pressure, and that comes from the Kardashian age we live in today.” She’s not alone in feeling the strain: a recent study of 1,300 British teenagers from researchers at the University of Birmingham found that the pressure to post flattering selfies online was creating body dissatisfaction and misery among schoolchildren. The most popular body type being celebrated by these young people? A slim waist, large breasts and hips – sound familiar?

According to data from Mintel, 22% of consumers say that social media influences the clothing they buy, a figure that rises to 64% in the Generation Z (under 22 years old) demographic. “It accelerates a cycle of spend-consumption,” Church-Gibson says. “It is worrying, how fast this process moves.”

To make this fashion even faster, brands have relocated their manufacturing back to the UK in order to shorten the time between seeing an outfit online and purchasing it. Leicester’s once-ossifying garment industry has cranked back into production. While this might sound like good news, an FT investigation recently found evidence of workers being paid below minimum wage. Low-cost retailers facilitate impulse purchasing with a “‘test and repeat’ strategy,” explains Saisangeeth Daswani of the trends intelligence company Stylus. “They’re producing very small quantities of many different styles, within a short turnaround time of approximately two to four weeks.”

Should we care that armies of young women are clothing themselves in one-wear outfits? During the 2018 British parliamentary inquiry into fast fashion, MPs accused Boohoo of selling cheap dresses that charity shops were likely to snub.

“I never thought I’d see the day when Topshop would look like couture, but with the rise of even cheaper brands like PrettyLittleThing, it’s making it look that way,” says Orsola de Castro of the sustainability campaigners Fashion Revolution. “If you’re buying a dress that costs £8, approximately less than a meal, inevitably someone along the supply chain, if not quite a few people, will be suffering.” A recent Fashion Revolution study found that British consumers care the least about the impact of disposable fashion of all the countries they surveyed. There was more public outrage when Burberry burned its excess stock, De Castro says, than when the Rana Plaza collapsed. “It’s difficult to make consumers empathise with workers … they feel their lives are hard enough, and can’t identify with someone else’s hardship.”

In an age of low pay and general economic malaise, you can understand the appeal of a £4 dress that makes you feel, however fleetingly, like a Kardashian. “If you’ve worked hard, you deserve to feel good, and when you’re dressed in clothes that you love, you feel good about yourself,” says Hassan.

But what makes this Kardashian aesthetic so appealing to young women? “The look is always the same,” Church-Gibson observes. “It always follows the same shape. Everything is tight; the heels are very high.” High-fashion designs are put through a Kardashian filter, such as when Kim wore a Celine dress in March 2017. “The Celine aesthetic is very loose, and worn with sneakers, but she paired it with very high heels,” Church-Gibson explains, describing the Kardashian aesthetic as “sexy, rather than fashionable”.

Church-Gibson has watched the Kardashian influence spread like a virus through British wardrobes with dismay. “What worries me is that everybody looks so similar. The look they’re selling is total, from the top of the head to the sole of the foot … it’s a very homogenous way of looking.” She mentions the style blog Man Repeller, which began as a celebration of fashion trends commonly thought to repel men: acid-washed harem pants, shoulder pads and dungarees. The Kardashian aesthetic is the anti-Man Repeller look; a hyper-feminised, high-glamour look that seems calculated to entice the male gaze. Acolytes of the Kardashian style “do look very sexy, but they are interchangeable”, says Church-Gibson. “In a way, it’s the death of individuality.”

And while the Kardashians are sometimes celebrated for popularising a new, more curvaceous “slim-thick” body type, it’s a shape that is arguably as inaccessible as the very slim ideal that preceded it. “They’ve simply helped swap one unattainable beauty standard for another,” says Yomi Adegoke, a freelance journalist and the co-author of Slay In Your Lane, who has written about the Kardashian influence in beauty. “The ideal has been replaced with a want for ethnically ambiguous women with curves, but only in certain places. It’s more like a Mr Potato Head approach to beauty, picking the ‘best bits’ from various different races and leaving women of colour, specifically black women, still at the bottom rung when they only have ‘parts’ that are deemed worthy and beautiful.”

Will anyone break the Kardashians’ stranglehold on the fashion industry? “There’s no end in sight,” concludes McClain. “The only people who may usurp them in the future are the next generation – their own children.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.