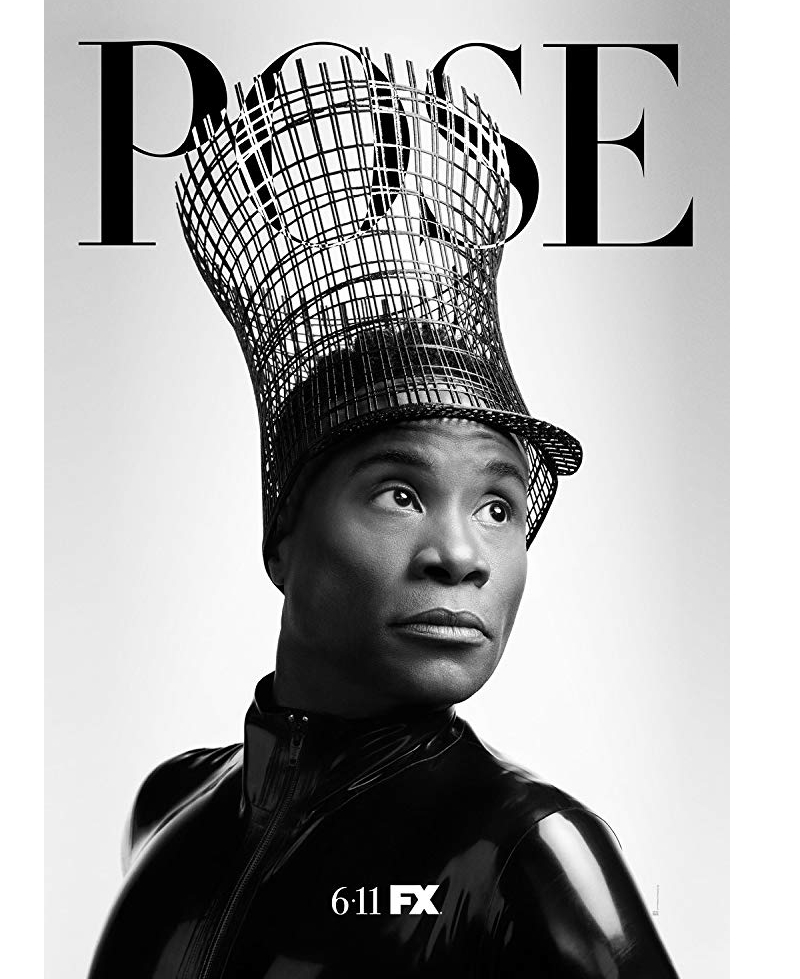

In the first episode of Pose – the hit drama about the 80s ballroom drag scene that gave birth to vogueing – a group from the House of Abundance break into a museum exhibition of Elizabethan-era clothes. They strip the mannequins, stuff the corsets and ruffs into shiny black bin bags, then escape through a smashed window to the ball competition. “The category is Bring it like Royalty,” says the MC, Billy Porter as the gang walk and pose in their Renaissance era garments. They win the competition, but their victory is about not only looking great whatever the cost, but also about breaking with convention, law and history.

In Cheer, Netflix’s docudrama about a competitive cheerleading squad, the breakout stars are Jerry Harris and La’Darius Marshall. Unapologetically exuberant, the black, gay teenagers in Republican-supporting, gun-toting Navarro, Texas, should stick out like sore, if deeply fabulous, thumbs. Yet Cheer becomes a story of how they survived grief (the premature death of Jerry’s mum and La’Darius’s suicide attempt) and accepted themselves. In both shows, as black and Latino members of the LGBTQI community, these characters are outside mainstream society and so have created their own. In this world “being fabulous” is not just the defining quality, but acts as a challenge to the status quo and (white, entitled, birthright) privilege.

The concept of fabulousness is said to have begun in the drag subculture and with Crystal LaBeija, who is seen as the founder of ballroom’s “house” culture (alternative familifabulousnesses for members of the LGBTQI community who have been kicked out of their homes). Pepper LaBeija, from Crystal’s house, was featured in Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning which brought ballroom culture to a wider audience.

It was in this film that many first heard the words that make up the lexicon of fabulousness. Words such as “work!”, “fierce”, “gagging”, “yaaaaas”, “slay” and phrases such as “giving me life” and “serving a look”. Although TV shows such as Absolutely Fabulous, Sex and the City and America’s Next Top Model brought these phrases and concepts into people’s homes, it was RuPaul’s Drag Race (now in its 12th season) that truly bought the concept of fabulousness into the mainstream.

Jinkx Monsoon, who won the fifth season of Drag Race, says both drag and fabulousness are about creating your own destiny. “We’re born into this world, and told from day one who we’re supposed to be,” she says. “We’re told at a very early age that we’re expected to behave, dress, and think certain ways – all because of what is between our legs. Drag is casting all of that off, and deciding for yourself who you want to be.”

But the concept of “fabulousness” is also, says Madison Moore, the author of Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric, a lifeline for people who belong to more than one disempowered or persecuted social group and therefore face intersecting prejudices. “Fabulousness is about the risk of stretching out and expanding when you have been told you don’t deserve to exist.”

In his book, Moore sets out four traits that define fabulousness: firstly, it does not take a lot of money; secondly it requires a high level of creativity; thirdly it is dangerous, political, confrontational, risky and largely (but not exclusively) practised by queer or transgender people of colour and other marginalised groups. Finally it is about “making a spectacle of yourself because your body is constantly suppressed and undervalued”.

Because of this, fabulousness is not to be confused with being camp – because it is inherently political. Susan Sontag in her influential 1964 essay Notes on Camp (the inspiration for the theme of the 2019 Met Gala), defined camp as an aesthetic sensibility devoid of any deeper meaning.

But Moore points out that for marginalised people, “there’s no such thing as style for style’s sake. Fabulous people are taking the risk of embracing spectacle when it may perhaps be easier, though no less toxic, to normalise. This is very different from how camp is typically discussed.”

In 2020, the concept of “fabulousness” is everywhere: in Lil Nas X’s mashing up of neon disco colours with cowboy style or each time Pose’s Billy Porter wears a traditionally non-masculine outfit on the red carpet. Both style statements challenge the white, cis-gendered status quo.

Yet, while mainstream culture has absorbed elements of black culture, such as the adoption of the fabulous lexicon into everyday conversation (“yassss kween”) the outsider status has not disappeared. “Being a black body, a black queer body, a black trans body, a gender nonconforming black body in public space is always vulnerable,” says Moore. “You can’t go shopping while black. You can’t go swimming while black. You can’t enter your dorm room while black. You can’t exist in your own home while black. You can’t drive in your car with a white girl while black. You can’t buy designer clothes while black. You can’t wear a hoodie while black. The list continues.”

During New York fashion week, the collection from the Anna Wintour-anointed African American designer Christopher John Rogers displayed a level of extreme fabulousness. His show featured largely non-white models sporting outfits in shocking shiny disco colours (fuchsia, emerald green and orange) and cut to massive proportions in geometric shapes that looked straight out of the Teletubbies. As Robin Givhan said, the show’s aesthetic appeared as if it were stylistically influenced by: “[the Diana Ross film] Mahogany, Ebony Fashion Fair (which ran from 1958 to 2009), drag balls and Instagram selfie filters.”

The models stopped dramatically at the end of the runway pausing for the endless clicks of photographers. They strutted in a knowing parody of fashion cliches. “Our shows are filled with a ton of emotion and energy so we encourage the models to feel themselves and the fantasy when they get on the runway,” Rogers tells me after the show. “It’s really about their personal attitudes and moods coming through.”

For the designer, his shows are an expression of “encouraging people to take up space and be the most themselves.” Does he think it is important to express fabulousness in the current climate of political divisiveness? “Absolutely,” he says “There’s so much vitriol and pessimism in the air towards individuals who don’t fit certain moulds, so it’s nice to combat that with true expressions of self, in whatever form that takes. The most effective, in some instances, is radical, boisterous personal style.”

Pat Boguslawski, the movement coach who choreographed the model Leon Dame’s strutting, angular walk, which went viral at the SS20 Maison Margiela show, says he was inspired to bring individuality back to the runway. “A fashion show is not just about mannequins and watching the clothes, it’s about creating a show. So we hire dancers, have amazing lighting and great music. I think a fashion show should be a show.” For him, Dame’s walk was an expression of his individuality. “As a movement director I’m creating something based on (a person’s) character, on who they are.”

Being “who they are” is a key narrative element of Pose. Angelica Ross, who played the spiky Candy, says the show is important on multiple levels. “To quote (Pose producer and trans activist) Janet Mock: ‘We have to say these things cause no one else will.’ Pose told a story that no one else wanted to tell as evident by the many ‘nos’ that (creator) Steven Canals received when initially pitching the project. It’s not only important that Pose told our stories, but told them right by including folks from the (LGBTQI) community at all levels of production.”

Fabulousness is a much needed state of mind in the current climate. As Ross says: “Being fabulous means feeling free to be yourself. It’s not fabulous if it’s fake.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.