Congratulations to Dame Zaha Hadid, who has been named as the 2016 recipient of the Royal Gold Medal.

Given in recognition of a lifetime’s work, the Royal Gold Medal is approved personally by The Queen and is given to a person or group of people who have had a significant influence ‘either directly or indirectly on the advancement of architecture.’

In the rural outskirts of Chongqing, where the sprawl of the Chinese megacity begins to give way to rice fields and power stations, two bulbous glass and steel mounds sprout from the earth like some exotic fungus.

It is the unmistakeable signature of Zaha Hadid, the Iraqi-born London-based architect, who on Thursday was announced as the 2016 recipient of the RIBA royal gold medal, one of the highest accolades in the profession. The first woman to be awarded the prestigious gong in her own right, the 64-year-old has earned a place as one of the most sought-after architects in the world, having bestowed her trademark blobs on cityscapes from Baku to Guangzhou.

Yet the Chongqing mushrooms in question are not hers at all. They are the doppelgänger of a project she designed in Beijing, Wanjing Soho; but such is the speed of the Chinese counterfeit industry that the fake was completed before the original had barely broken ground.

When I visited the project last year, the brazen developer was candid: “In China,” he told me, “imitation is the greatest form of flattery.”

It is an apt illustration of the irresistible allure of Hadid’s dynamic swoops and complex curves, a futuristic language that has spawned a generation of imitators across the globe. More than any other architect, she has promoted the culture of computer-generated “parametric” design, creating worlds where walls melt into floors, where ceilings billow and bulge, where facades dissolve into perforated skins and rippling veils. For better or worse, it has become the go-to style for art galleries and opera houses, corporate pavilions and sports stadia, used by many a budding mayor the world over to make their “iconic” mark.

Peter Cook, one of the founders of the radical 60s Archigram group and one of Hadid’s former teachers at London’s Architectural Association, sees her as one of the finest minds of her generation. “For three decades now, she has ventured where few would dare,” he writes in the gold medal citation. “If Paul Klee took a line for a walk, then Zaha took the surfaces that were driven by that line out for a virtual dance and then deftly folded them over and then took them out for a journey into space.”

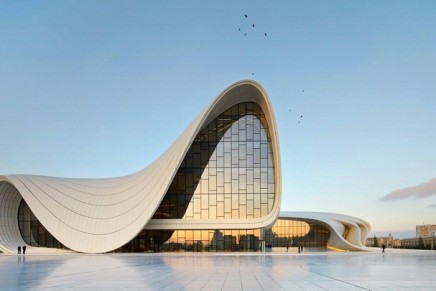

Her cosmic dance perhaps reached its most exuberant peak in the Heydar Aliev centre in Azerbaijan, completed in 2013. It is a whipped meringue of a building that ripples across the site in taut waves, enveloping an ethereal space that feels like being swallowed into the belly of a ghostly white whale. Yet, to make this thing happen, 250 homes were demolished and families were forcibly evicted, the project tarnished by the tyrannical regime’s catalogue of human rights abuses – a factor that has since plagued Hadid’s other projects, including the World Cup stadium in Qatar.

She is characteristically blunt when such matters are raised. “I think that’s an issue the government – if there’s a problem – should pick up,” she told the Guardian, when challenged over the conditions of workers in the Gulf. “It’s not my duty as an architect to look at it.”

Her duty, as she sees it, is to conjure forms never before imagined, spaces never once dreamt. And, at their best, the results can be compelling. Swimming beneath the grey belly of the London Olympic aquatics centre can be a sublime experience, the great concrete tongues of the diving boards licking up above the pool. But where the building meets the outside world, and people are forced to enter through what feels like a service entrance, it falls short.

It is often the case with her projects: when the exotic forms concocted on Planet Zaha have to interface with reality, things don’t always work out. Pay a visit to the Serpentine’s Sackler gallery in Kensington Gardens and you’ll see how painful the clash can be, where her undulating white pavilion sits like an Ascot hat clumsily propped against the handsome brick gunpowder store.

Still, her projects have nonetheless been showered with accolades, twice receiving the Stirling prize – for the MAXXI museum in Rome and the Evelyn Grace academy school in Brixton – and she was the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker prize more than a decade ago, making RIBA’s choice now seem a little like it is trying to catch up. It is a vote of confidence, a morale boost perhaps, for an architect who recently lost the prestigious commission for the Tokyo Olympic Stadium, her design having faced a tirade of criticism from local architects since its unveiling, being compared to everything from a bicycle helmet to a child’s potty.

She receives the medal in part for her influence beyond buildings. Indeed, “Zaha” has grown into something of universal brand. She has designed a handbag for Fendi, vases for Lalique, and a perfume bottle for Donna Karan, as well as the obligatory luxury yacht – and even a raunchy range of swimwear, leading to rumours she was starting her own fashion label. Last year she unveiled her own lifestyle collection at Harrods, featuring scented candles, sinuous cups and a set of acrylic serving platters for £9,999.

But the ride to global ubiquity and expensive tabletop trinkets hasn’t always been an easy one. Born in Baghdad in 1950, Hadid studied mathematics at the American University in Beirut before coming to London in 1972, where she studied at the AA, then a hotbed of wildly experimental design.

After working with her former tutor Rem Koolhaas as a partner at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, she established her own practice in 1979, but didn’t get a chance to build until 1993 – with a small fire station for the Vitra furniture manufacturer in Weil am Rhine. The building’s wayward walls soon drove the firemen mad and it was not in use for long.

Hadid continued to be dismissed as a “paper architect”, her dramatic paintings of colliding shards, inspired by Russian suprematism, deemed destined never to leave the drawing board. The loss of Cardiff Bay opera house – a competition she won in 1994, but which was never built – was a particular blow, and she didn’t realise her first UK project until the Brixton school in 2010.

She has more than made up for it since, building opera houses in China, art museums in America and car factories in Germany, all bearing her unmistakable influence in every detail. As Peter Cook puts it, comparing her position to Frank Lloyd Wright: “Zaha shares … the precious role of towering, distinctive and relentless influence upon all around her that sets the results apart from the norm.”

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.